According to the grim estimates of the ongoing Sixth Mass Extinction, about 500 species that roam the land are expected to go extinct soon. The figure, in my opinion, should read 501.

For the Odia thakur — that famed and fabled Brahmin cook — who once lorded over the Bengali hneshel seems to be threatened with oblivion too.

The word on the street is that Thakurpatti, near Sovabazar Rajbari, has long been taken over by the Brahmin’s doppelgänger: he looks like him, cooks like him — well almost — but is not perched as high on the caste ladder.

In fact, the faux thakur has a twilight ancestry. A certain Jagadananda, or so goes the lore — Swapna M. Banerjee’s engaging Men, Women & Domestics mentions this mythic man — had apparently started a factory to cook up Brahmin thakurs, passing off non-Brahmin Odias as bona fide high-caste bawarchis.

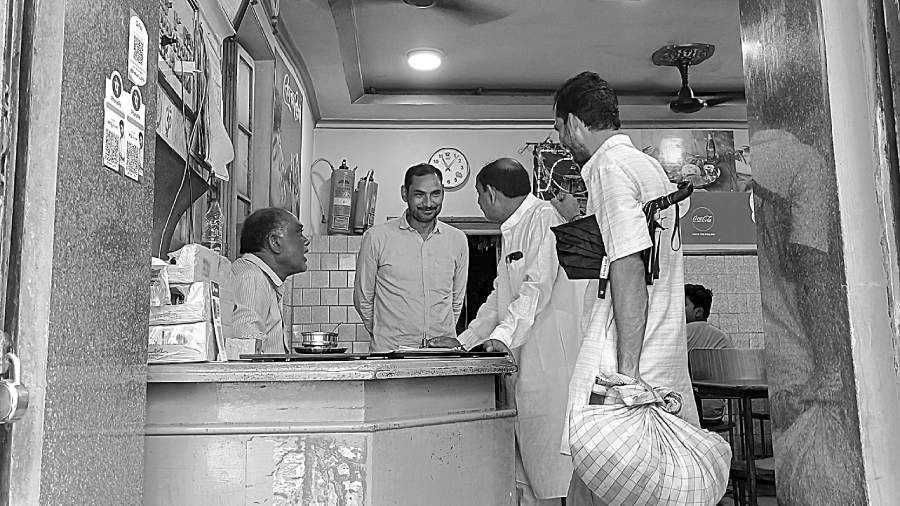

Fact has begun to mirror fiction. A recent article in The Telegraph, which captured, quite imaginatively, the tale of a nonagenarian rice hotel in its own voice, mentioned the paucity of both Odia cooks and Odia patrons.

So off I went to the land of Utkalbashis in the hope of getting a glimpse of the bamun thakur bearing a ladle.

Only to be disappointed by Bhubaneswar’s Old Town. Famished after spending an afternoon trying to spot the Yakshi’s head — the one Feluda rescued — amidst the mind-boggling array of figurines that stud the façade of the Rajarani temple, I made my way to Shirose hotel for a bite of authentic Odia lunch. There was no doubting the authenticity of the dishes I wolfed down: chingri’r malaikari with diced ginger in, what I was told is, true-blue Odia fashion, a mutton curry in a delicious thick, brown gravy, soft rutis, followed by roshogolla’s rival, the rasagola. Confident that the meal could have only been rustled up by untainted Odia hands, I walked into the small kitchen to congratulate the cook who — to my utter horror — hailed from Bengal.

Undeterred, I made my way to a small dhaba that claimed to sell dalma from Chandanpur, a village famous for this exquisite, quintessentially Odia broth of lentils and vegetables, the following day. The dish — piping hot — was being served on shalpatas. On enquiring about the caste antecedents of the thakur, the driver of the vehicle I had hopped in said, quite gruffly, that caste does not matter in Navinbabu’s Odisha.

The rejection tasted bitter. So I headed for a Pahala sweet store located next to the Bhubaneswar-Puri road. Stacked in front, at eye level, was a diabetic’s dream — hillocks of chhena poda, chhena gaja, chhena jhili, rasabali. But here too, instead of spotting a poite — the sacred thread worn by Brahmins — dangling from the attendant, or hearing chaste Odia, I only caught the sight of a burly, caste-indeterminate servitor and heard a smattering of Telugu. An entire slice of Andhra Pradesh had descended upon the sweet shack, intent on flattening those edible, saccharine mounds of sweets.

Desperate, I turned to the sea — I mean Puri’s sagely nulia by the sea. I figured that the wise man, who could read the waves, may direct me to the elusive bamun thakur on land. I was, indeed, given a direction — towards Konark.

The next day, thirsty and hungry, I entered a nondescript restaurant next to the highway that led to the realm of the Sun God, opened its tattered menu card and read the following in Odia-Hindi — “Bhuk se badkkar koi Dharma or Roti se bada Iswor koi nahi na hoga”.

I was convinced I had found, at long last, my bamun thakur. Who else would write such pearls of wisdom while managing the haata-khunti? The food was delicious: crisply fried sea fish, a surprisingly light chicken broth in spite of its fiery redness, ruti and assorted vegetables.

This time, I adopted a different sleuthing tactic. Having tipped the attendant generously, I asked him if I could have a word with the cook. To my surprise, he, having pocketed the money, said I couldn’t, and pointed heavenwards. Good heavens! Had the cook passed away?

The answer came in the form of a deep rumble, the sound of thunder, from the second floor that was a private chamber. It was the Lady of the House — Odisha’s proverbial Bianca Castafiore — barking orders to the trembling attendant to carry the next bowl of curry downstairs for hungry hearts.

I had found my cook — finally — a fierce thakurani instead of a thakur — democratising a tradition once monopolised by privileged men.