James Augustus Hicky, an eccentric Irishman from England, who had tried to make a living as a physician, sailed to India to make a fortune in the 18th century. India was then under British rule. Hicky arrived in Calcutta, the then capital of British India, and launched Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, the first printed newspaper in Asia, on January 29, 1780. He fearlessly took on the establishment and set the trend for generations to come.

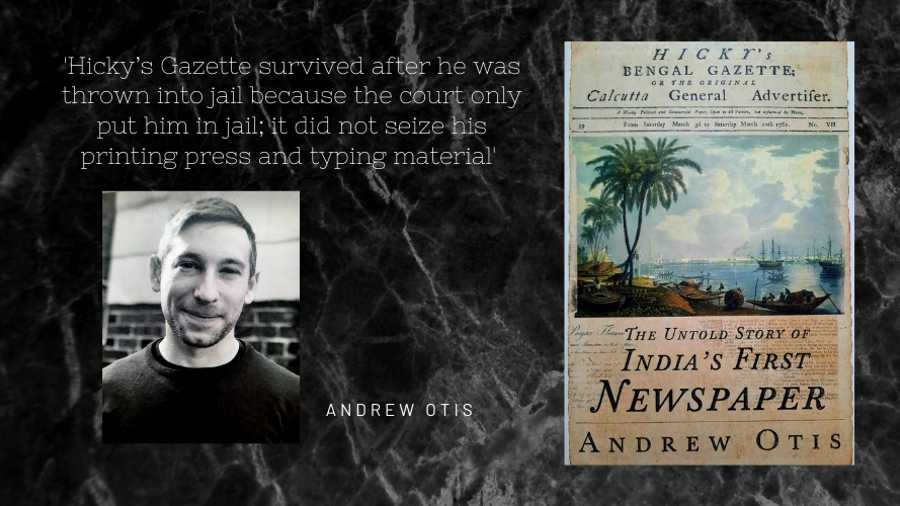

Dr Andrew Otis, a Fulbright fellow from the University of Maryland, USA, spent two years in Calcutta trying to unearth the details of Hicky’s tremendous legacy. His work culminated in a book: Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper. Now, over two centuries later, Hicky’s intention to take on the establishment, the East India Company and Governor General Warren Hastings, holds relevance, the need no doubt heightened by times we live in. The English-language weekly newspaper, published from Calcutta, was Hicky’s mode of hitting back at obstacles in his path to expose the vested interests of the government. The upheavals that Hicky staunchly countered serve as beacon of motivation for mediapersons of today.

Otis speaks to The Telegraph Online on the implications of Hicky’s brand of journalism that has stood the tests of time, on the 242nd anniversary of the Gazette.

Excerpts:

TTOnline: Hicky introduced the maxim: ‘Open to all parties but influenced by none’ on the masthead of his paper, Hicky's Bengal Gazette. Does your research indicate the evolution of this phrase?

Andrew Otis: Great question. The “open to all parties but influenced by none” masthead was used by at least two American newspapers: the Massachusetts Spy and the Virginia Gazette, dating back to at least 1771, but as to how it evolved I can't really say. I haven’t come across other newspapers using it but I haven't searched thoroughly. Hicky first used it in May, 1780. Hicky must have come across one of these American papers and borrowed the slogan. The fact that these newspapers say they are “influenced by none” would indicate that they would not be coerced by British colonial government. Why these newspapers chose these specific words is a great question though and probably worth its own research paper.

Your book gives vivid details about Hicky's consternation over Governor-General Warren Hastings bribing the Supreme Court judges and Hyde's testimony. Tell us a little about your findings?

One reason Hicky was so concerned about the judges is because they were supposed to be independent of the East India Company, appointed by King and Parliament. At first, the Supreme Court was fulfilling its role, issuing subpoenas and habeas corpus to protect residents of Bengal from undue imprisonment by the Company. What basically happened is that at one point there was a showdown between the Court's sheriff and the East India Company army, which left the court's powers in limbo.

At that point Hastings made overtures to each of the judges to see what it would take for them to stop getting in the way of the Company’s tax collection. These judges had their own political ambitions. (Chief Justice Elijah) Impey wanted a seat in Parliament, and Judge Chambers wanted to be a member of Hastings’ council. Judge Impey and Judge Chambers both accepted bribes, but the last judge, John Hyde, refused. Hyde was more of an idealist and wrote that the court should have jurisdiction over all individuals in Bengal.

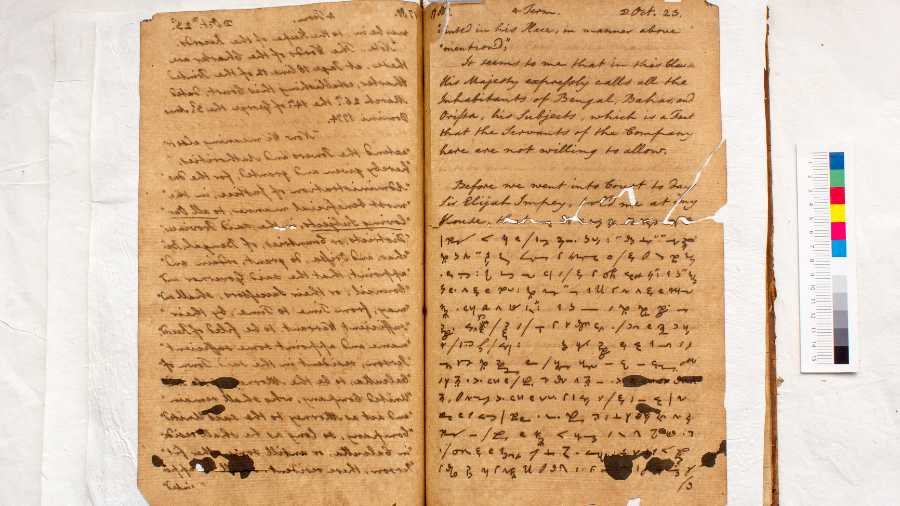

Hyde secretly recorded the bribes. In one entry he wrote: “I think it a vast degradation of Impey to accept such office in the service of the Governor-General and Council ... [this is] a direct breach of the Act 13 G 3rd which prohibits his taking presents or any other emolument than the salary.”

Hyde later wrote: “I will take nothing from the Governor and Council nor from the Company.”

A page from Judge John Hyde's diary where he ferreted information in coded language. Picture courtesy: Andrew Otis

Hicky's “vox populi vox Dei” slogan must have touched his readers because many of them came out in his support when he was being hounded by the government. How did the Gazette survive after Hicky was thrown into jail?

Hicky’s Gazette survived after he was thrown into jail because the court only put him in jail; it did not seize his printing press and typing material. So even though Hicky was in jail, he could still print his newspaper because he had assistants who were probably doing the physical printing outside jail. It was only in March 1782 when the court issued an order to seize his printing press and material that his newspaper was shut down for good.

Would you say Hicky and his crusade had a role in the impeachment of Warren Hastings and Chief Justice Impey?

I’d say Hicky definitely helped. Many of the accusations against Hastings were first printed in his newspaper. This publicity is probably where Hicky helped the most, as impeachments are ultimately a matter of public opinion and whether parliaments or representative bodies are willing to act.

Hicky wasn’t totally forgotten when Hastings was being impeached. One newspaper in London wrote this editorial: “The case of Mr. Hicky was attended with circumstances the most shocking and dishonourable to the laws of any country; that he was condemned to severe and close imprisonment (which in that hot climate is worse than suffering immediate death) that he was debarred all communication with his friends; that the jury in question were composed of men, everyone of them high in office, dependent on the Governor’s immediate pleasure. I leave the public and all men who are conversant with business, to judge what redress an unfortunate man could hope for in such hands from a packed selection of placemen.”

What did you discover about Hicky’s opinion and action on Robert Clive's hypocrisy that led to the hanging of innocent Indians like Nanda Kumar?

I think that article was about the extent of it. Both Clive and Nanda Kumar had long since died so it wasn't “new” news, but it was a good political point to make in a newspaper.

After Hicky's death, what happened to his paper and how did Asia’s first newspaper pass on to Indian ownership? Did you discover when the letter ‘s’ stop looking like an ‘f’?

When Hicky died in 1802, Paul Ferris, one of Hicky’s former assistants, went to his estate sale and appears to have purchased and preserved a collection of Hicky’s Bengal Gazette. I mention on page 251 of my book that Ferris ran a printing shop (and a bookstore) and was a collaborator with Ganga Kishore Bhattacharji (I've also seen his name spelled Bhattacharya). Bhattacharji began the first Indian-owned newspaper, the Bengal Gazette, in 1818 and was quickly followed by Raja Rammohan Roy. Ferris doubtless showed Bhattacharji Hicky’s Gazette and helped transfer knowledge. For what it’s worth, the collection of Hicky’s Gazette preserved by Ferris now resides at the University of California, Berkeley.

Also, the ‘s’ letters generally stop looking like ‘f’ around the year 1800. This was a general trend among many English language-speaking areas.

What was your research experience in Kolkata like? Did you manage to get the documents on Hicky at Calcutta High Court?

The documents I was looking for were in the Centennial building, an annex of the court. The process was extremely inefficient. Records were sometimes stored in folders between wood slats organized year by year. Every time I wanted to see some documents, they required a peon to open them for me, one at a time. There was no catalogue or index either. I had heard that sometimes election ballots were stored in the building but that didn't seem to be the case when I was there. Other archives were generally easier to access. But for the life of me I couldn’t understand why bringing a laptop to take notes would cause so many problems or create so much paperwork.

The writer, Sudipta Bhattacharjee, is a journalist, a professor of media science and also a Fulbright fellow.