Book: After Sappho

Author: Selby Wynn Schwartz

Publisher: Picador

Price: ₹499

Discussing the pruning of roses, Vita Sackville-West had once mused, “[t]here is so much to be said, and so many different types of rose to deal with, that it all becomes confused and confusing.” Generations of writers grappling with history have been likewise troubled. How can a novelist map a tangled wilderness of historical data onto a plot? How can a scholar contain a wildfire of world-changing passions in 300-odd pages? As Vita goes on to advise, “[t]he only thing is to be bold; try the experiment; and find out.” Encountering its own overabundance, Selby Wynn Schwartz’s Booker longlisted After Sappho responds in kind with a provocatively genre-bending experiment.

The blurb calls it a series of “cascading vignettes”; the author calls it a “work of fiction” or “a hybrid of imaginaries and intimate non-fictions, of speculative biographies and ‘suggestions for short pieces’.” It quotes, summarises and ventriloquises documentary sources (“‘a diverse archive of biographical acts’” and secondary scholarship) upon a scaffolding of advocacy. The result is a poetic phylogeny of the lived histories of lesbian/bisexual feminist, avant-garde artists in France and Italy of the Belle Époque and War years that does the ‘-isms’ impeccably. The project has several discernible objectives: to recover lesbian lives and loves from historical and/ or heteronormative obscurity, indicate their collective role in bringing the discourse of female same-sex desire into the twentieth century, and signal the ways in which they impact the early years of the European feminist movement. But, above all, this book seeks to rally queer women in the sacred name of Sappho.

The title and opening lines make clear the status of the most mysterious of lesbian lives: Sappho is the causa sui first mother, structuring metaphor and authorial sign. The book is haunted by more than forty female presences, but all channel the spirit of Lesbos like a Sybil or a Cassandra: “Becoming Sappho was not play-acting in a garden! It was living the rites among the people who had tended the ancient shrines.” Anne Carson’s tremendous translations of Sapphic fragments are called into symbolic, allegorical, tonal and syntactic service. For instance, the first-person plural narrators invoke “[t] his feeling that Sappho calls aithussomenon, the way that leaves move when nothing touches them but the afternoon light”, the kletic poem “ever dappled and shining”, and “the genitive of remembering.” Our narrators, sometimes bewildered like a Greek chorus but always omniscient, seem to possess erudition, but it is not worn lightly.

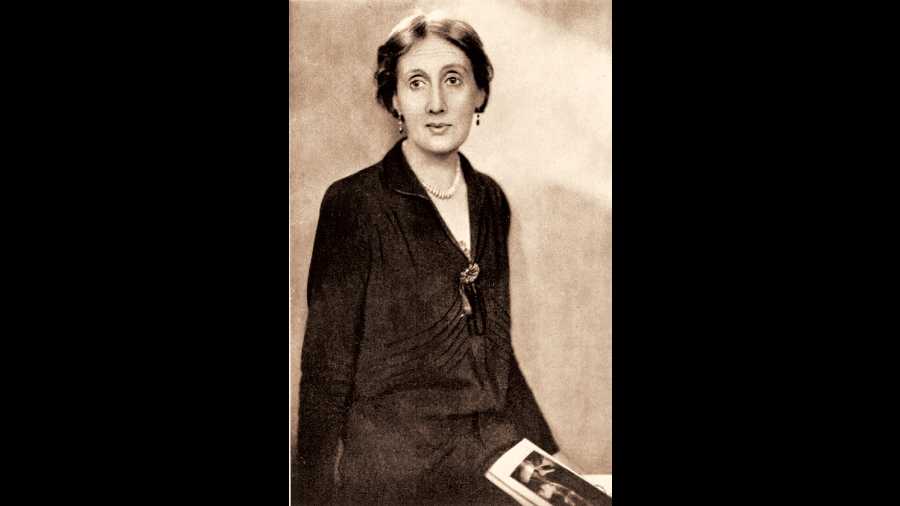

Apart from the one poet to rule them all, three major figures hold the book together: Lina Poletti (1885–1971) in Italy, Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) in England and Natalie “The Amazon” Barney (1876–1972) in France, building primarily around Barney’s celebrated Parisian salon. The narrators take appropriately imaginative liberties in sketching the complex and overlapping romantic, sexual, literary and professional relationships that obtained among these women. However, a sense of the individual is sacrificed upon the altar of relationality. As the narrators say, “[w]e wrote the lives of Lina Poletti, but we did not always understand them.” This is then a studiedly distant reading of lives. Some of the women documented in the book were widely admired, lived openly nonconformist lives, and produced or patronised remarkable art. It is not enough to pick, magpie-like, at nuggets of information and digest the extraordinariness of these lives into networked superficiality. Effective fiction must engage with its characters’ motivations, express the good, the bad and the indifferent in them. It must at the very least try to understand Lina Poletti. Speculative biography falls flat if all lives become one, radiantly shaking in eternal textual sunshine.

While this exclusion of interiority stems from a thesis-level privileging of superficial (read erotic and artistic) affinities, other exclusionary measures arise out of outrage at the injustice that women and lesbians have suffered historically. Most men are written out (“a... swift cut, and history is sutured without them”) citing another data point, Vita. While Oscar Wilde gets honorary membership in Sappho’s club, it is queer that the sexologist, Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935), who was a pioneer in the advocacy for homosexual and transgender rights and coined the sympathetic descriptor, “sexual intermediaries”, for the gender spectrum, has no place in the story. Geography, too, seems to be a policy for exclusion.

After Sappho is not for the uninitiated. It does not provide enough factual or emotional content for the casual reader to imaginatively engage with its topic. Flummoxed by its own fecundity, it rehearses the rhetoric of openness and intimacy but remains stubbornly opaque. Vita had suggested in her gardening piece, “[e]ven the smallest garden can be prodigal within its own limitations,” but it required lavishness and generosity to make it so. Schwartz’ book would have benefitted from her advice.