Book: Everyday Reading : Hindi Middlebrow and The North Indian Middle Class

Author: Aakriti Mandhwani

Published by: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs 599

In a culture sustained on the myth of hyperactivity, reading is an increasingly rebellious act. There has arguably been a mass exile from the landscape of books to the hyperspace of screens and pop entertainment. Global debates on the death of print culture have naturally gained momentum. In this age of the decline of the print industry, Aakriti Mandhwani’s fascinating book on the history of North India’s “middlebrow” print magazines and reading habits impresses print’s unshakeable historical value.

In her detailed introduction, the author strategically explains what she means by the term, ‘middlebrow’, by drawing from its historical explanations by various other scholars. With the birth of a new nation, art and literature adapted to the demands of its people, creating a range of art objects that served them beyond the prescriptive tenets of a fledgling democracy permitting, in turn, the evolution of personal introspection and individual pleasure through the act of reading. How did the middlebrow magazines and Hindi paperbacks of the time deal with such fraught subjects as nationalism, religion, caste and class? Mandhwani anticipates these questions even when the art objects she investigates gloss over them. The book offers keen insights into history from the bottom by discussing the kinds of stories, essays and cartoons that these magazines published.

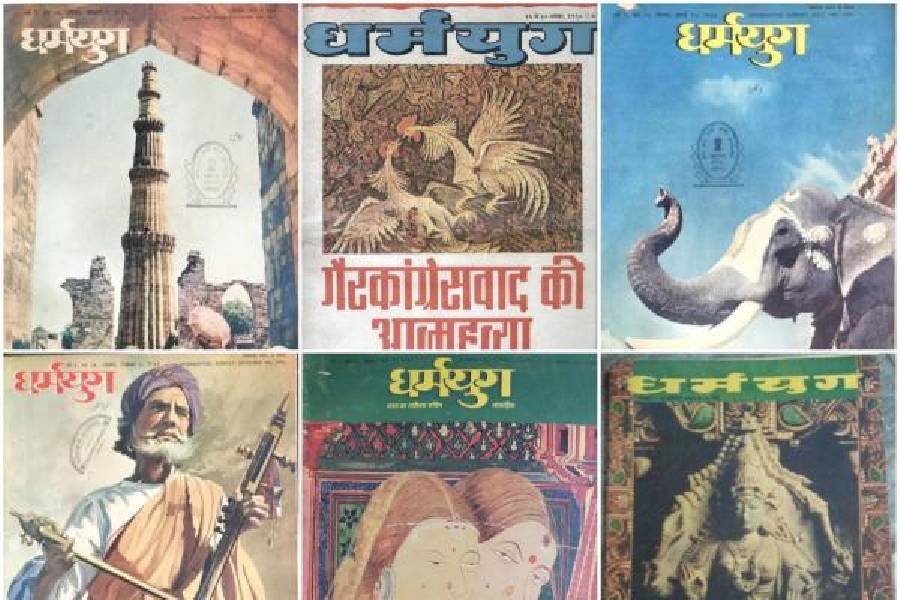

Divided into four chapters, the book taps into the history of Delhi Press’s popular magazine, Sarita; the Hindi paperbacks from Hind Pocket Books; and the diverse range of world literature offered in Dharmyug. In the final chapter, there’s a comparative analysis of middlebrow publishing with three “lowbrow” magazines of the time. The structure of the book is clear and precise. But the author seems to often give in to the overcautious persuasiveness of an academic. Some arguments seem repetitive; others are pushed hard like in an academic proposal trying to convince itself of its validity. Despite these mild distractions, this is undoubtedly an important book that is expertly researched. Mandhwani also advocates how the middle-class family in North India not only consumed art and literature but also enforced the production of the art objects they consumed.

What demands special mention is the book’s cover — Meena Kumari reading a book on the set of Pakeezah. The cover is artfully realised every time Mandhwani discusses how women consumed and produced the middlebrow art objects being discussed. Everyday Reading informs us that reading has always been a stubbornly singular engagement demanding an unwavering commitment. Which is perhaps why it has always been subversive.