Book name- GANDHI: THE END OF NON-VIOLENCE

Author- Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee

Published by- Vintage

Price-Rs 699

Writing in 1936, M.K. Gandhi agreed with a characterisation that he was not as much a votary of ahimsa as he was of truth. In other words, “he was capable of sacrificing non-violence for the sake of truth”. A decade later, these twin commitments were put to a fiery test. From August 1946 till his assassination in January 1948, India descended into a spiral of violence and death. In Gandhi’s heroic response, truth and non-violence became indistinguishable.

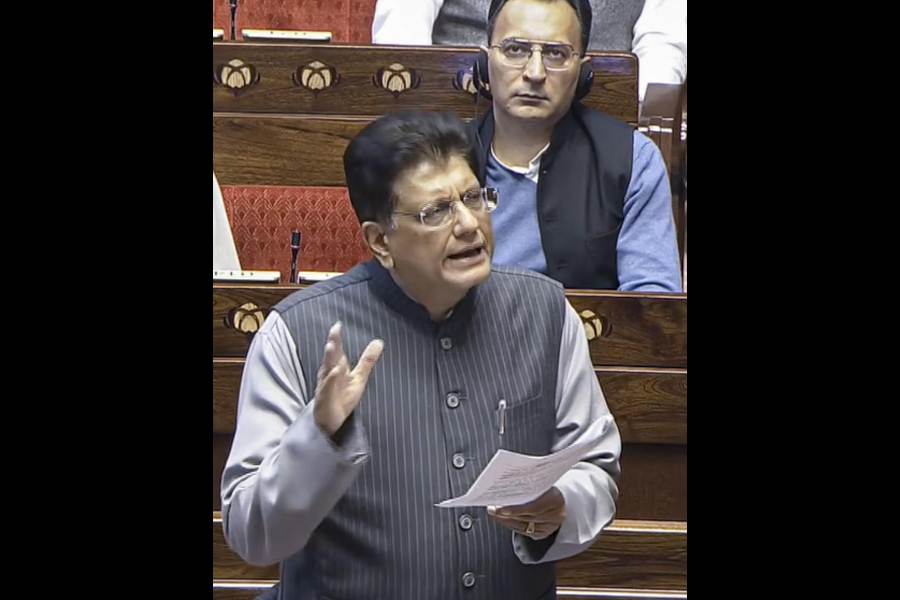

Gandhi: The End of Non-Violence is a philosophical examination of the fate of non-violence that emerged in this period. While it covers the events in Calcutta (now Kolkata), Bihar and the city of Delhi, the primary focus is on Noakhali (now in Bangladesh). The volume pays significant attention to the killings in Noakhali, the dubious role of the Muslim League as well as Gandhi’s fierce moral struggle in that region (picture). A noteworthy aspect of the volume is its use of Tridip Suhrud’s recently published English translation of the diary of Gandhi’s grand-niece, Manu. Apart from a sensitive treatment of Gandhi’s controversial brahmacharya exercises, we have a portrait of the admirable psychological growth of a young woman thrown into a fierce maelstrom. She emerges as an acute observer of the human condition as obtained in extremely disjointed times.

Through the non-violent emancipation of India, Gandhi had sought to free the world of the curse of colonialism. But at the very moment of the end of Empire, India succumbed to the impulse of hatred and Britain criminally abdicated its responsibility. Deeply disillusioned and psychologically lonely, this was a moment of searing clarity for Gandhi. The non-violence India had practised in the previous decades was that of the weak, one that was being openly disavowed. It is this transformation that the subtitle, The End of Non-Violence, alludes to.

But Gandhi did not succumb to the darkness that enveloped his mind. To use Gene Sharp’s memorable title, in this period, Gandhi Faces the Storm. He unflinchingly put his creed and his own self to the ultimate test — the conquest of the fear of violence, nay, that of death itself. In the same sense, as the volume demonstrates, Gandhi had not moved to Noakhali to give succour to the survivors but to imbue them with courage. A deeply unsentimental Gandhi demanded it. In facing the challenge to non-violence in Noakhali lay the future of India.

Ambitious in scope, the volume wishes to seriously think about “Gandhi, Partition, non-violence, genocide, ethics and truth”. Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee also seeks to be unconstrained by the ideological baggage of “interpretation and certainty”. Being a philosophical exercise, the volume eschews definitive conclusions. The result is thoughtful and demands contemplation. The writing is clear and has a ruminative quality. But a discursive style does not allow for a substantial engagement with the many, larger-than-life themes addressed. Often one misses adequate signposts that enable a general reader to navigate through the thicket of historical context and philosophical high-stakes.

The volume also pays attention to the “politics of historiography”. Interspersed throughout the discourse, a number of histories of late-colonial Bengal and Indian nationalism are flagged and subjected to serious scrutiny. Bhattacharjee is highly critical of what he regards as ideologically-motivated writing. In particular, he vehemently disagrees with what he characterises as attempts to deflect or diminish the role of the Muslim League and absolve the Muslim peasantry of Noakhali for their role in the violence unleashed on Hindus. This aspect of the volume is unusually frank and takes no prisoners. The criticism is severe but earnest. However, philosophy and historiography work in different registers. The admixture of immiscible themes makes for an uneven outcome. Here, one notes that the repeated use of the term, “genocide”, raises many serious questions that cannot be addressed in this brief review.

In many places, the volume suffers from inadequate editorial attention. For instance, in the front matter, abhaya is spelt abahya. There are many sentences with no spaces between words which is surely not intended as scriptio continua.

Gandhi: The End of Non-Violence engages with the critical question of non-violence, one with an unmistakable contemporary resonance. Here, one has to take the finality of the subtitle as a figure of speech and not a historical fact. As the author himself notes, Gandhi distinguished between the idea of ahimsa and its fallible practice. One hopes, and Gandhi would have readily agreed, that the singular example of his life does not exhaust future possibilities. As he told us, truth and non-violence are as old as the hills.