Book: SEVEN DEADLY SINS: THE BIOLOGY OF BEING HUMAN

Author: Guy Leschziner

Published by: William Collins

Price: Rs 394

This book documents the experiences of certain individuals who have experienced traumatic brain injuries or have suddenly suffered the after effects of inherited genetic mutations, detailing how such conditions have transformed previously ‘normal’ personalities, stripping away social inhibitions to reveal behaviours society deems repulsive. Structured around medical conditions corresponding to lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride — these empathic studies, reminiscent of Oliver Sacks, complement Guy Leschziner’s efforts to explain the neurobiological origins of these behaviours.

The strengths of Seven Deadly Sins lie in its exposition of what Leschziner, a practising neurologist in London, calls the “neurological worldview”: the fact that our mental worlds are entirely the product of a kilogramme of jelly-like matter within each of our skulls and that our cherished prejudices, our minutest thought-fragments, our psyches and personalities are “simply a function” of neurons, neurotransmitters, and trillions of synaptic circuits working in response to an evolving information architecture pre-determined by genetics. The unsettling implication is that each of us might be nothing more than complex ecological systems optimised over millennia to ensure the survival of our gut bacteria and viruses but one thing is for sure, there is no such entity as the soul or the mind existing independently of our brains.

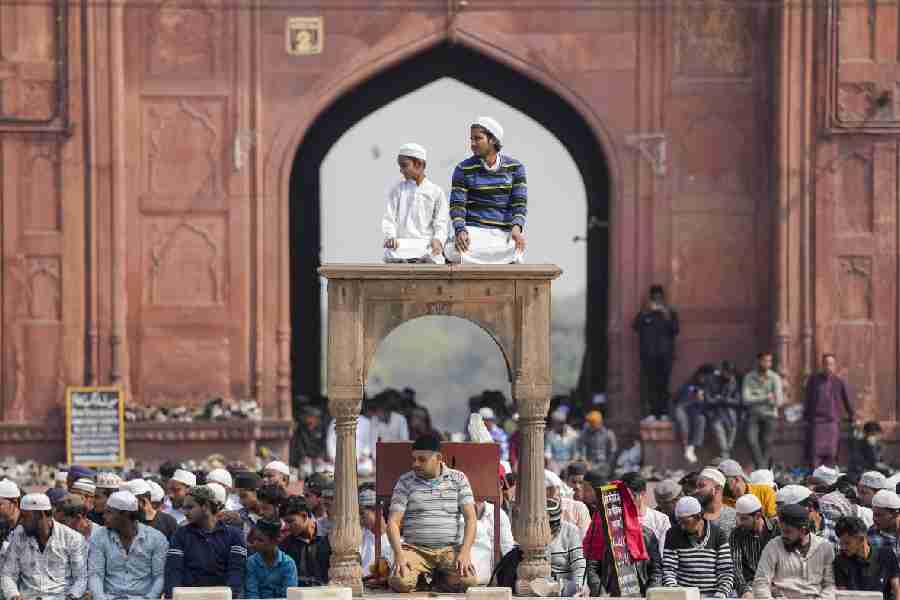

Perhaps the book might have been better if it communicated a more nuanced understanding of the histories of the idea of ‘sin’ across civilisations and cultures. In Christian theology, sin is understood as a separation from the powers and the protection of the divine, an assertion of oneself as a causa sui (a cause unto oneself): the expression of personal disconnect with a mysterious, divinely-grounded existence. Correspondingly, the Seven Deadly Sins, formalised by Pope Gregory I in 590 CE, were considered “capital sins” because they were believed to cause, through the isolation of the individual by way of the guilt generated through bodily actions and material desires, a rupture with the divine. Though beliefs corresponding to ‘sin’ exist in other religious systems, the concept is not universal: colonial-era missionaries often struggled to convey its implications to diverse indigenous peoples who lacked an analogous cultural term. As cultural anthropologists, from Ernest Becker to David Graeber have pointed out, we now recognise this difficulty stemmed from the missionaries’ sheer disbelief in the lived realities of the indigenous peoples who lived their ‘sin-free’ lives without conceptual equivalents of isolation or alienation, their identities deeply intertwined with their societies and the worlds that they lived in, manifestly divine.

Another important omission in this stock-taking of human sins is the cruelty of ‘normal’ humans towards other life forms — as remembered in the unfeeling, merciless flogging of a horse that drove Rodion Raskolnikov, literature’s most celebrated murderer, to tears and rage in his childhood, or, in a different order of reality, pushed Nietzsche into the dark abyss of irretrievable mental collapse.

That said, at the threshold of incomprehensibility, the book does introduce lay readers to interesting contemporary debates in clinical neurology about the ‘readiness potential’ (Bereitschaftspotential), which posits that complex neural processes in the brain are making cerebral decisions (whether to eat biryani or pizza, to turn right or left, to procrastinate, to push or not to push the slobbering zombie whom you’ll encounter during your Metro ride home) long before we are consciously aware of making them. This has important consequences for our belief in volition and ‘free will’: the everyday (or the philosophical, Being-and-Nothingness kind of existential) perception that we have the freedom or conscious choice to make decisions is sadly nothing but an illusion; a cosmic farce, perhaps orchestrated by stardust and mischievous gut bacteria out of their own inscrutable boredom.