Book: FORGOTTEN: SEARCHING FOR PALESTINE’S HIDDEN PLACES AND LOST MEMORIALS

Authors: Raja Shehadeh and Penny Johnson

Published by: Profile

Price: Rs 699

Ever since Israel’s disproportionate — genocidal — military response to the grisly attack on its territory by Hamas, the world has been a witness to Gaza’s decimation in many forms. Over 50,000 inhabitants, a vast number of them children, have been killed by the Israeli military. Gaza’s infrastructure, including hospitals and schools, lies in ruins. The conflict and Gaza’s resultant destruction, as is the case with modern wars, have been documented extensively. The photographs, satellite images, social media posts, which, among other sources, make up the visual register of, as well as bear historical testimony to, this annihilation impress upon the mind the effacement of Gaza as a physical site. Skeletal buildings, streets strewn with rubble, bombed out houses dominate this representational archive that brings evidence of the crippling — effacement — of Gaza’s physicality.

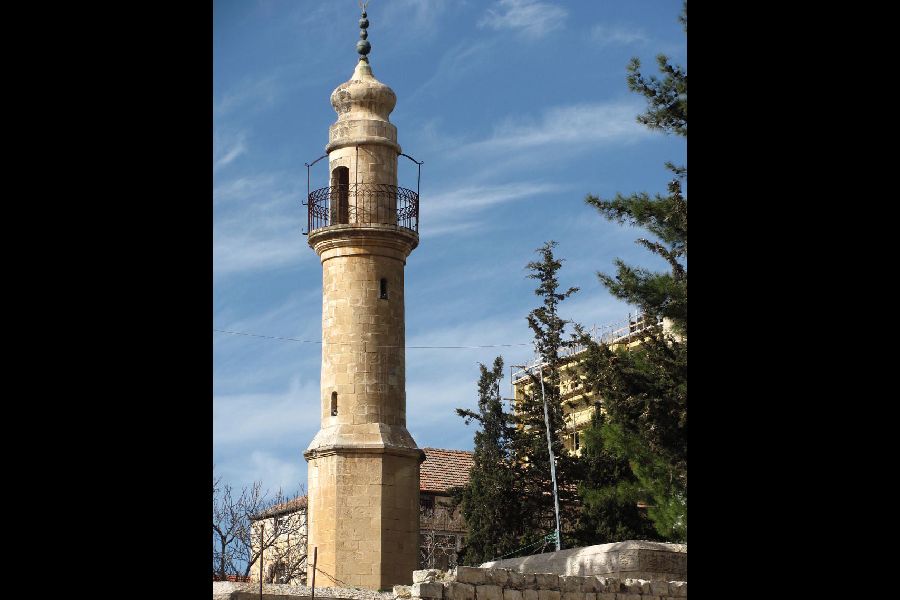

But Gaza and other Palestinian territories that have, over the years, been encroached upon by Israel, have witnessed another kind of erasure — gradual, targeted, and barely visible to or acknowledged by the world outside: this constitutes the obliteration of the markers of Palestine’s history. In Forgotten, one of Palestine’s most prolific writers, Raja Shehadeh, and Penny Johnson, an informed commentator on West Asia, come together — the narrative uses the first-person plural — to retrace, literally and figuratively, in the years after the pandemic, the disappearance of mosques, memorials and other crumbling edifices in Israel and the West Bank. Gaza eludes the duo because of blockades and, later, the seemingly endless conflict that makes a journey impossible. But Shehadeh and Johnson succeed in offering glimpses of the faint — fading — outlines of Palestine’s material history from other parts of its contested territory.

Forgotten ought to be read as an act of resistance. For it is an attempt to resurrect, memorialise, Palestinian history in the face of formidable intrusions into it by the Occupier that seeks to further alienate a subjugated people from their own territorial roots, thereby divesting them of the right to own their memory. What Forgotten unveils is not unsurprising: a bitter battle between the occupier and the occupied to be the custodian of a people’s history. This is a conflict that has taken place, and is unfolding, in other parts of the world. But what Forgotten lays bare clinically, with urgency and poignancy — and this where it derives its importance — is the lived experience of a people who are undergoing the process of the expunging of their history and artefacts. The book is also an important interrogation of the idea of nostalgia, which is often believed to be a kind of longing that is benign. But Forgotten digs up nostalgia’s political roots, albeit within a specific context, to suggest that collective wistfulness has a subterranean force, a morality, to transform nostalgia into not only a kind of defiance but also a just demand for the acknowledgement and the protection of a people’s past that is now besieged.

The authors’ documentation of Israel’s decades-long agenda of the expunction of Palestinian lineage in the historical sense is detailed. The challenges that Shehadeh and Johnson are made to confront in the course of their search — institutional obstruction, neglect, wilful or otherwise, of Palestinian historical sites — make the narrative despairing, even exhausting. The findings, though, are illustrative. For instance, the word, “Nakba”, the writers discover, does not feature on the stone pillar, the only memorial in Kafr Kanna in Galilee to that monumental event; Jib, a city that once dwarfed Jerusalem and was home to a sophisticated and ancient water system, is being threatened with Israel’s “salvage archaeology”, a preparatory ritual before the onset of territorial exclusion; perhaps the most striking illustration of such loss and its subsequent memorialisation is Palestine Connected, an installation by the artists, Iyad Issa and Sahar Qawasmi, that conjures the railway station of Nablus that was once connected to other parts of the Palestinian geography.

In his books, Shehadeh has often been criticised for presenting a one-sided — prejudiced, in other words — account of aspects of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Forgotten’s writers make sporadic attempts to understand how segments of Israel’s population view their country’s predations on Palestine’s history. For instance, they mention how residents of Kibbutz Baram had shown an interest in knowing what had come before them: essentially, the forcible displacement that had been brought upon the village of Kfar Bir’im by Israel’s army. But Shehadeh and Johnson also note that decades of litigations, joint marches with Israeli activists and “honest conversations” with kibbutz residents have not made a difference to the shifting ground reality.

Forgotten comprises numerous images that testify to Israel’s war on Palestinian history. The production of these images, unlike the text, fails to hold the readers’ attention. This is unfortunate because better photographs and an imaginative design could have amplified the impact of this important book.