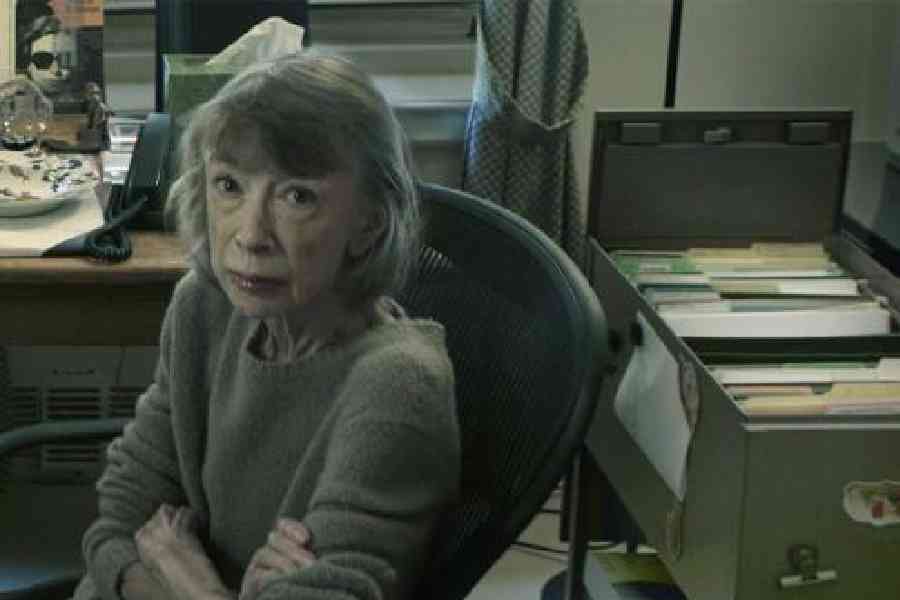

Book name- NOTES TO JOHN

Author- Joan Didion

Published by- Fourth Estate

Price- Rs499

In a landmark 1972 essay in Esquire, Tom Wolfe defends The New Journalism for its ability to pull the reader emotionally into the spirit of the age. These new writers, he declares, “seem to be saying: ‘Hey! Come here! This is the way people are living now — just the way I’m going to show you!” Joan Didion’s reportage upon the death of the American dream, delivered by a journalistic “I” that spits out one shrapnel sentence after another in tight-lipped disdain, can indeed deliver the immersive truthlikeness of the new style that Wolfe extols. However, when the same clinical gaze turns towards the self as an object of dissection, that glamorous Didion po-face in dark glasses ossifies into an impermeable membrane. I remember being distressingly unmoved by both The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011), trying to make out why I was so put off by her attempts to speak the unspeakable after having lost both her lifelong partner, John Gregory Dunne, and her adoptive daughter, Quintana Roo, in 2003 and 2005, respectively. I decided that it was possibly because Didion preferred to tell me about her love rather than try to make me feel it with her and, thus, remained indifferent to her loss.

Didion’s posthumously published latest book is, therefore, doubly unnerving. It is deeply autobiographical, since it deals with her trying to resolve the “problem” of Quintana, who had turned alcoholic, depressive, and suicidal by 1999. But the manuscript was not prepared for publication by the author. Titled by the unattributed editors as Notes to John (2025), it is a record of a year of Didion’s weekly sessions with the prominent psychiatrist, Roger MacKinnon. The papers were found amongst miscellaneous documents and are addressed to “you”, her husband, but since John was present in one of those sessions, the editors “assume that the reports were not simply for the purpose of bringing him up to speed”. One could also ‘assume’ that Didion wrote them because for her writing was “work” and workaholism is an addiction, as Dr MacKinnon reminds her in one of the sessions. She could also have been trying to control therapy-speak since “the ability to think for one’s self depends upon one’s mastery of the language” (Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968). It could also simply be because, in her famous pronouncement, “we tell ourselves stories in order to live” (The White Album, 1979).

Didion started sessions with Dr MacKinnon upon the advice of her daughter’s therapist, Dr Kass, who thought that Quintana’s alcoholism and mental health issues derived from a co-dependent relationship with her mother. This leads to some bizarre situations in the book as we eavesdrop upon the analysand’s reportage of the two doctors discussing their patients and playing mediators.

“I said I knew she (Quintana) had always thought of me as fragile.”

“She does. I would imagine most people would do. It’s not just your physical fragility, it’s the way you relate to people, the closeness of your emotion to the surface — everything about your emotional tone seems fragile. But you’re not. You’re really extremely strong.”

“I said a friend had once remarked that while most people she knew had very strong competent exteriors and were bowls of jelly inside, I was just the opposite.”

“That’s remarkably acute. If you’ve never told that to Quintana, I think you should. Preferably the next time you see her.”

It is clear that MacKinnon is a validating father figure. He is made to say things like “Other people — myself included — see you as extremely caring. On the other hand, if you saw yourself that way, you wouldn’t be here.” His words, quoted as if verbatim, although they could not possibly have been, give her understandable reasons for explaining away unbearable realities. It is telling that not for one moment is the possibility of paternal transference acknowledged by any party involved.

Reading between the lines, the book allows for much speculation about the Didion-Dunne family situation, contextualisation of the autobiographical canon, and revelation of the tragic consequences of anxious attachment in parenting. The enormity of Quintana’s predicament, however, hardly registers. The doting mother shows little tolerance for the tormented and wayward child, but radiates waves of fear, worry, and irritation instead: “it had occurred to me at several points that I didn’t like her.” The sad thing is that for all the desperate attempts at forging self-regard through expert sympathy and blame apportioning, we suspect that the patient did not like herself much either.

In one of the rare moments when Quintana’s voice is heard in the text, she is reported as saying that “however interested she might be, it was no one’s business what got

said to or by the psychiatrist.” In a spirit of respect for the deceased, ought we, then, to have made this business ours?