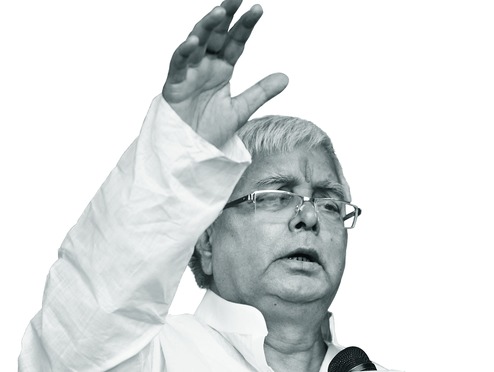

The ditch is not an unfamiliar place for Lalu Prasad. He came off it to begin with - a buffalo-boy from a boondock called Gopalganj in riverine north Bihar. He's been flung back there often, in person, as metaphor. He keeps coming back.

He has arrived the previous night from the consequences of a ditch he dug long ago - the fodder court's dock in Ranchi. Patna itself feels no less than a ditch - the Nitish ditch. Tomorrow he must demonstrate yet another time he still possesses the bone and nerve to claw out of this current ditch - the assembly lines for the "BJP hatao, Desh bachao" rally are awhir. The town lies bombarded ahead of the battle cry - banners, barri- cades, high-base bombast and bluster, Patna is a barracoon of arriving brigades from Bihar's far corners.

Across the road from the Lalu clan's home sprawl on Circular Road, a mammoth cut-out of the patriarch is being wheeled somewhere, prone, shuddering on a handcart. Lalu himself is lumbering this morning, weary from the late evening road ride from Ranchi. He has ambled down his private quarters - in a summer vest, his white wraparound tucked loosely, hitched up his shins, a motion away from being girded to the loins for a pit-fight - and settled into a padded rattan chair under an outdoor awning. He looks whacked, but not enough to be deadbeat. " Bahut tang karta hai... dagabaaji kiya, gherabandi kiya,agency, inquiry, raid... Lekin chhorenge nahin, ladenge," he says about nothing in particular; it sounds like a note-to-self spoken out... They harass me a lot, they stabbed me in the back, they've laid a siege, agencies, inquiries, raids... but I shan't spare them, I'll fight. He signals to an aide and he fetches a pinch of khaini; this is a morning ritual so old it has taken on a robotic air, the palm opens up and tobacco comes to drop on it. Lalu tucks it under his lip, winces, then spits it out. "Struggle hai, ladai hi ladai, aage aur ladai, laao laathi, ladenge..." He is laughing an incredulous laugh.

" Kya bataaven, election hum jeeta iske liye, humko hi kursi se nikaal diya, dhoka de diya... bhoolenge nahin, aur log badla lega... What's there to tell. I won the election for him and he ousted me from power, betrayed me... I won't forget, and the people won't forgive.

A torrent would take Patna the following day, hundreds of milling thousands. Gandhi Maidan, the staging post of countless political war cries, would resound anew with endorsement: Laaaalooo Yadav kiiii...

This man can still look deficits in the eye and dare them; he can still summon a storm and unleash it on adversity.

Consider the odds Lalu has waded against these past decades, the most obstructive of which, quite certainly, is Lalu himself - a goliath riven by faultlines of his own authorship, at once the conjurer of promise and its exterminator.

He arrives on the stage like a bolt in 1990 and turns Bihar to blight. Fifteen straight years in power. Fifteen fairly besmirched years - the absence of governance, near-zero development, personal and political scandal, dubious, often criminal, company, excessive nepotism, destructive populism, astounding chicanery and chutzpah. When the fodder embezzlement unseats him in 1997, he pulls wife Rabri Devi out of the kitchen and instals her chief minister. He is able to not only keep her in power the next three years, but also script an electoral return in 2000.

He is toppled from presidentship of the Janata Dal on revelation of fodder misdemeanour, he pulls out and pitches his own, and flourishing, tent - the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD).

He is summoned to court by a trial judge. He sets out on an elephant, as if it were his baraat, followed by a sweeping fan-tail. He is charged with presiding over jungle raj; he uses the invective to inspire victimhood in his constituency and makes a virtue of alleged vice - "They are calling Bihar a jungle and that makes all Biharis junglees, they have insulted you!" That is how the election of 2000 was won.

He is by law barred from contesting elections and holding public office upon being convicted of illicit profiteering from the fodder mill in 2013, but comes roaring back in 2015, owner of the biggest bag of seats in the Bihar Assembly, a feat - no less - achieved against the run of play and widespread prediction.

Through his worst years, after losing power to the Nitish-BJP combine in 2005, Lalu remains a force to reckon with. His individual following has nearly always topped the Bihar charts, close to an average 20 per cent of the vote share. King, kingmaker, chief challenger - since Lalu entered the public arena nearly 30 years ago, he has either held power or hovered close to it.

In a sense Lalu represents an intractable condundrum to his party, at once its biggest asset and liability. With him at the top, the RJD crown will forever bear the dent of misdeed and infamy; with him not there, there isn't a crown. It's why Lalu is able to do his willing, often excessively, often to his detriment. It's why he is able to nudge aside senior, and loyal, colleagues like Raghuvansh Prasad and Abdul Bari Siddiqui and promote what is already a dynasty voluptuous with competing political ambitions - eldest daughter Misa was fielded in the 2014 Lok Sabha election. She lost and was paradropped into the Rajya Sabha. Younger, and probably pet, son Tejashwi was negotiated into deputy chief ministership of Bihar when he had only won his first ever seat in the Assembly. Elder son Tej Pratap was installed health minister. None of them has yet displayed the remotest promise of inheriting either Lalu's stage charisma or his backstage skills. But inherit they will, on insistence and as a matter of right. Lalu's job it is to pick their battlefields, plot their campaigns, tutor them on what to say - and what not - manage their victories, play promoter-impresario. Lalu's colleagues carp and grumble over being sidelined; occasionally one would even take a pot-shot at the anti-dynast Lohia socialist having turned a dynast himself. But none of them are able to bring grouse or grievance to their lips in Lalu's presence. They know just how desperately they need Lalu at the helm, warts and all.

There is also about Lalu, after all, an unalloyed nativism that offsets much of what's negative about him. There's a court beyond the formal and the prescribed, the legal and the correct, whose loyalty he has come to evoke. Across Bihar's rural heartland, and especially in hamlets and villages of Saran, his home patch in north Bihar, Lalu inhabits quite another image - "our man". Neither middle-class/upper caste disapproval nor legal stricture - and, it must be said, not least the follies and frailties that run rampant in the Lalu scheme itself - have quite come to bear adversely on him in that court. Every rejection of Lalu has brought a counter-echo of renewed espousal - Lalu Yadav, the one we love because you hate him. Part of the reason of this impregnable suzerainty Lalu has crafted is the esteem and entitlement he brought to large communities that had long been on the socio-economic margins, and the sense of security he brought to Bihar's substantial minority population at critical hours. Since he halted L.K. Advani's "Ram rath" in 1990, he has held on to that tether and never wavered. Standing resolutely by the minorities, and against the Sanghi project, whose aggressive embodiment the Narendra Modi regime has come to be, is a singular differentiator between Lalu and the man he has shared power over Bihar with. Inclusive discourse has remained his holy grail. Lalu never ever collaborated with the BJP, not for anything. Nitish Kumar did. For power. He cried "Sangh-mukt Bharat!", then submitted to it. Lalu continues to rail against the Sanghi worldview, Nitish has embraced it.

At the height of his reign in the mid-1990s, few leaders enjoyed such fanatical mass adulation as Lalu; there was a long period he seemed palpably invincible. At his worst, following Nitish Kumar's takeover in 2005, Lalu still enjoyed close to 20 per cent of the Bihar vote, thanks in the main, to the sense of belonging and indebtedness he had imbued his core constituency with. It is fair to suggest, even today, that all of Lalu's misappropriations and mismanagement as one-time potentate of Bihar have not pushed him into political arrears. He is in a ditch, but it's no place he is unfamiliar with.