|

|

|

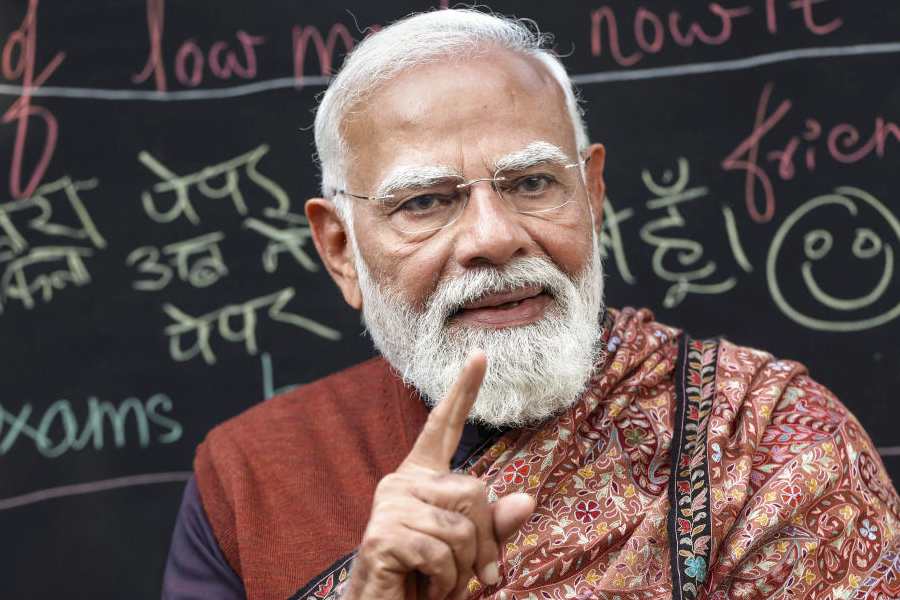

| UNEASY CALM: (From top) King Gyanendra; pro-Maoists demonstrate in Kathmandu; Maoist chief Prachanda |

Rabindra Nath Sharma knows the Nepal King and his ways. And yet, he wasn't prepared for this. One evening last November, the 75-year-old chairman of the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, Nepal went to see King Gyanendra at his Nagarjun Palace, atop a forested hill on the outskirts of Kathmandu, Nepal's capital. Nearly seven months had gone by since a popular uprising had forced the king to give up the power he had seized in a coup of a sort in February,2005.

Sharma, who was a Cabinet minister in Nepal during the regimes of King Mahendra and his son King Birendra, the late father and the assassinated brother of the present king, expected to see a “broken” man, stripped as he was of his constitutional powers as head of the state. Instead, he found the king “amazingly relaxed and supremely confident.” Sharma wondered why, for the “situation outside his palace was not in the least in his favour,” he says.

Three months later— as the violent Terai agitation, which many blamed on monarchical forces, ripped apart the plains of Nepal and cracks started to appear in the ruling alliance over issues such as monarchy — it all became plain to him. Sharma realised why King Gyanendra seemed so “optimistic” and “uncharacteristically” generous that evening — he had even offered him a cup of tea.

Democratic forces in the Himalayan country were outraged when the fallen king defended his 2005 takeover in a message to the nation on the 57th Democracy Day in Nepal early last week. It seems that the trouble brewing in Nepal is good news for the country’s “suspended” monarchy. If the jana andolan (mass movement) hemmed in the king last April and forced him to hand over power to a seven-party alliance and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), the interim Girija Prasad Koirala government appears boxed in today, with the Maoists on one side and different ethnic groups on the other.

“It’s a very, very alarming situation. We are trying our best to control it but no one knows for sure what will happen in Nepal tomorrow,” says Nepali Congress leader Sujata Koirala, daughter of the Prime Minister.

True, the discredited king, who grabbed power on February 1, 2005, only to give it up on April 24, 2006, enjoys little popular support. But the same cannot be said of the monarchy, holds Nepal observer Dhruba Hari Adhikary, former president of the Nepal Press Institute. The tables, many hold, could be turned if things are allowed to slip out of control. And who knows that better than the king! So, far from fleeing Nepal, the king seems to be digging in his heels for the long haul.

The Terai agitation, which broke out in mid-January and left 28 people dead in three weeks, may have been quelled for now, with the Koirala government acceding to the agitators’ demands for proportional representation and increased seats in Parliament. But the issue smoulders. For, Madhesis, as the Nepalese living in the plains are known, want the right to self determination. The government is already grappling with similar demands from the janjati, a powerful ethnic group in Nepal .

With 75 districts and a population of some 25 million, Nepal may be a small country sandwiched between its two giant neighbours, India and China. But it has a large number of diverse ethnic groups with disparate languages. Once the ethnic Pandora’s Box is prised open, it is difficult for any government to slam it shut, says former Triubhavan University teacher Dev Raj Dahal.

To be sure, the future of Nepal’s fledgling democracy hinges, to a great degree, on the June election to the Constituent Assembly. The Assembly will not only draft the country’s new democratic Constitution but also decide the fate of the monarchy on the very first day of its first session. However, the election looks uncertain. The Nepal Election Commission says it is almost impossible to conduct polls in June as the government has not yet enacted the necessary laws.

The failure to hold the election on schedule could turn out to be catastrophic for the Koirala government as it will provide the besieged king with the much-needed time to recoup and strike back. As analyst Adhikari sees it, though the Nepalese Army has been stripped of its “royal” tag that preceded its name by the interim ministry and asked to report to the government, its two-century-old loyalty to the monarchy cannot be easily erased.

Maoists are acutely aware of the “ground reality” and want the government to declare Nepal a “democratic republic”, election or not. “If the election is not held and the government doesn’t declare Nepal a republic, there will be a massive public upsurge, a revolt,” Baburam Bhattarai, the number two in the Maoist hierarchy after Prachanda, warns. He accuses the “monarchical forces” of trying to scuttle the June election.

Judging by the recent turn of events, things could easily slip back to the days of Maoist violence which claimed as many as 13,000 lives in Nepal in more than a decade. Bhattarai also makes it clear that the People’s Liberation Army, as the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) calls its guerrilla wing, hasn’t yet “given up its arms” and that “we have only declared a ceasefire.”

If Maoists were to take up arms again — and this, Nepal watchers believe, is a distinct possibility — it could well be the end of the peace process in Nepal that started uneasily on November 25, 2005, with the Maoists signing a 12-point agreement with the seven-party alliance. Peace is clearly fragile in Nepal and, in the words of an American diplomat, the country is “not out of the woods” yet.

The biggest threat to the Koirala government comes not from outside, but from within. As a senior minister in the Koirala government puts it, if there is one thing that the seven-party alliance has in common with the Maoists, it is “mutual distrust.”

Sujata Koirala of the Nepali Congress accuses the Maoists of trying to”undermine” democracy by insisting that the country’s new Constitution “mentions no role” for the Opposition. “They actually want to grab power and run the country in their own way. They have a hidden agenda,” she maintains.

Yet no issue splits the seven-party alliance from its Maoist ally more than the fate of Nepal’s 238-year-old monarchy. The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) wants to abolish the monarchy, but its partners in government are not so sure.

Sujata Koirala says her party favours a “ceremonial” king but it’s for the people to decide. She fears that abolishing the monarchy could “destabilise” the country. “The king may be unpopular, but not so the monarchy,” she says.

Gopal Man Shrestha of the Nepali Congress (Democratic), a senior minister in the Koirala government, says the monarchy should be “eased out” but “not abandoned” if democratic Nepal is to have “a safe landing.” His suggestion: King Gyanendra be installed as the first interim president of Nepal. “Then he can fight the election and if he wins, he will continue or someone else will be the head of state.”

Support for the monarchy remains even outside the ruling coalition — and this, in some ways, explains the king’s confidence. Though his party voted in Parliament last year in favour of the motion to strip the king of all his powers, Pashupati Shumsher Rana, chairman of the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, in Opposition, says his party is yet to take a position on abolishing monarchy. Sharma of the Rastriya Prajatantra Party Nepal says the country doesn’t need “an absolute” monarch but it needs a “ceremonial king as a symbol of unity and integrity.”

“The monarchy will survive if it’s allowed to,” says former Nepal information and communications minister Shirish Shamsher Rana, who is close to the Palace.

Bhattarai, however, says the Maoist position on the monarchy is non-negotiable. “It’s a symbol of feudalism and an obstacle to development. It will have to go,” he says. He feels that in rising up against the monarchy, the people of Nepal amply demonstrated last year what they wanted.

“Why should they be now asked to choose between the monarchy and democracy?” he asks.

The question is pertinent, but a clear answer is still to evolve. For there is no one voice in Nepal .