Scientists have created an antivenom -- "the most broadly effective to date" --using blood donated by a person who developed a 'hyper immunity' to snake venom through snake bites and self-immunisations.

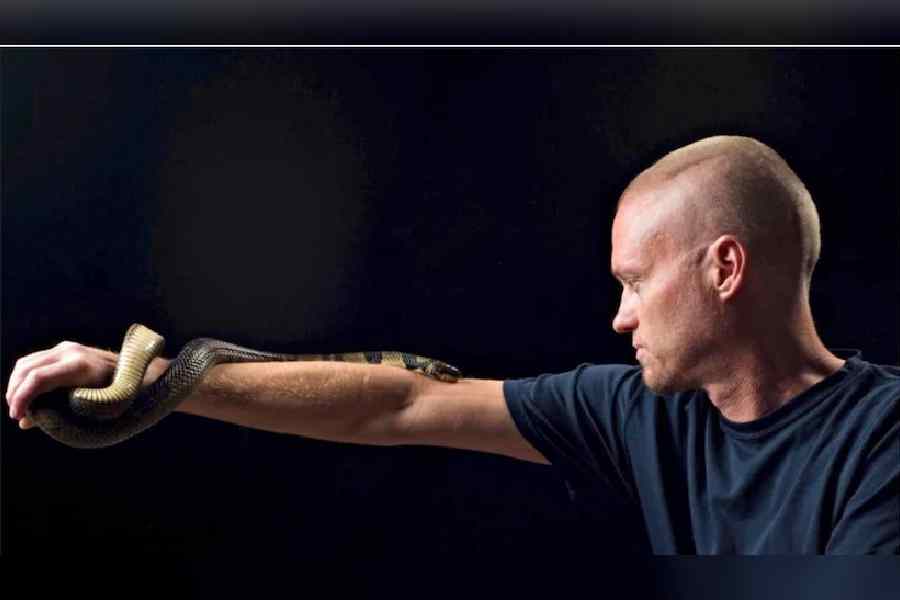

Over a period of nearly 18 years, the donor, Timothy Friede, exposed himself to 856 self-immunisations, including snake bites and doses of venoms of 16 lethal snake species, enough to "kill a horse", said first author Jacob Glanville, CEO of Centivax, Inc., a US-based vaccine developer.

Through his unique immune history, Friede's body had created antibodies that were effective in countering a broad range of snake toxins and "could give rise to a broad-spectrum or universal antivenom", Glanville added.

A study, published in the journal Cell, found that newly developed antivenom could protect mice against the venom of black mamba, king cobra, and tiger snakes.

Fascinated with reptiles and venomous creatures, Friede kept dozens of snakes at his home in Wisconsin, US. Curiosity and hope to protect himself from snake bites led him to inject himself with small doses of snake venom, slowly increasing the amounts to build a tolerance, the Associated Press reported.

He would then let snakes bite him.

"At first, it was very scary. But the more you do it, the better you get at it, the more calm you become with it," Friede told the Associated Press.

Snake venom is injected into a horse or sheep, which produces antibodies in response. These antibodies are used in making an antivenom, considered the only solution to treat a snake bite.

However, having been produced by animals, the antivenom can result in adverse reactions when used in humans, the researchers said.

Treating a snake bite also tends to be specific to a region or species of a snake, they said.

For developing the antivenom, the researchers separated the desired antibodies from Friede's blood. The antibodies were then tested in mice, which were infected with the venom of snakes from the World Health Organization's deadliest category 1 and 2 -- including about half of all the venomous species, such as coral snakes, mambas, cobras, taipans, and kraits.

The antibodies reacted with the toxins from these snakes to produce components that could render a venom ineffective.

The researchers could thus systematically create a "cocktail" comprising a minimum but sufficient number of components to render all the venoms ineffective.

Three major components were used in making the antivenom cocktail -- two antibodies from the donor and a molecule called 'varespladib', known to stop a toxin in its tracks.

"A 3-component cocktail rescued animals from whole-venom challenge of all species in a 19-member WHO Category 1 and Category 2 elapid diversity set, with complete protection against most snakes observed," the authors wrote.

The researchers are looking to conduct clinical trials in dogs affected by snake bites in Australia.

However, the research is still in early stages as the antivenom was only tested in mice and researchers are years away from human trials, the Associated Press reported.

"Despite the promise, there is much work to do," Nicholas Casewell, a snakebite researcher at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, and not involved with the study, told the news agency.

Even as the team's snakebite treatment shows promise against the group of snakes that include mambas and cobras, it's not effective against vipers, which include snakes like rattlers, according to Casewell.

About 81,000 to 1,38,000 people die each year because of snake bites, most of which occur in Africa, Asia and Latin America, according to the World Health Organization.

Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by The Telegraph Online staff and has been published from a syndicated feed.