Expansively, Foreign Minister A.K. Abdul Momen assures me, “With Sheikh Hasina here and Narendra Modi there, this is the Golden Age of India-Bangladesh relations”. I almost fall of my chair. Later, a close confidante of the Bangladesh Prime Minister, knowledgeable about the reality on the ground, says “our relationship has never been better. There are no outstanding issues of significance. Even the Teesta waters are flowing.” A former envoy to India adds, “Now, the relationship is on the right footing.” India’s current High Commissioner, Vikram Doraiswami, one of our brightest diplomats and a potential Foreign Secretary, in his virtual Ananta Aspen lecture at the India International Centre on 7 September 2021, endorses this positive assessment of our bilateral relationship:

“In the past decade, the India-Bangladesh relationship has been a consistent and bipartisan success… as Bangladesh has become our largest regional trade partner, development partner destination, source of inbound tourists, as well as a flourishing economy in which Indian investors and professionals find valuable opportunities.”

(Note the expression at the start of the passage: “in the past decade”, i.e., the decade plus of the ruling Awami League government. Will it survive an alternative government?)

These official statements are in such startling contrast to what I hear at think-tank meetings, informal conversations and dinner-party talk that the rift valley dividing civil society opinion from official assessments becomes glaring. The explanation, I think, lies in the difference between facts on the ground and people’s expectations and aspirations.

At one meeting, convened expressly for me to hear “the other side”, I am subjected to a torrent of criticism of India with a vengeance. One participant affirms that it is perceived in Bangladesh that “the Hasina government stands on the shoulders of India”. Another thunders, “India is appointing Hasina’s ministers”. A third weighs in, “This government is in power because of India”. A fourth accuses R&AW of being “too involved”.

As for India’s role in the Liberation War fifty years ago, one mild comment is, “Gratitude is there but cannot be perpetuated forever.” Another says aggressively, “There is too much projection of the Liberation War”. Yet another participant adopts a slightly more conciliatory line, “I expect India to be a big brother, but, as in all relationships, there will be good times and bad.” He disapproves of “finger-pointing” at India. “In our social media,” says someone else, “anti-India feelings are strong”- but I do not ask if that is the nature of the medium or the typical average national sentiment.

Mamata Banerjee with Sheikh Hasina Twitter

At the other end of the spectrum is a frequently elected Bangladeshi statesman who wants to see the India-Bangladesh relationship graduate from being a “stable relationship” to becoming a “special relationship” and progressing rapidly towards a “strategic relationship”. He sees Bangladesh as the “corner-stone” of Indian foreign policy (and vice versa) and believes the key to reaching hitherto unscaled heights lies in “unblocking” Bangladesh’s connectivity, in every sense of the term, to its natural economic hinterland in North-East India. To this end, he advocates anchoring our respective foreign policies in

(a) Eliminating communal tension; and

(b) Together combating poverty through market-induced regional cooperation.

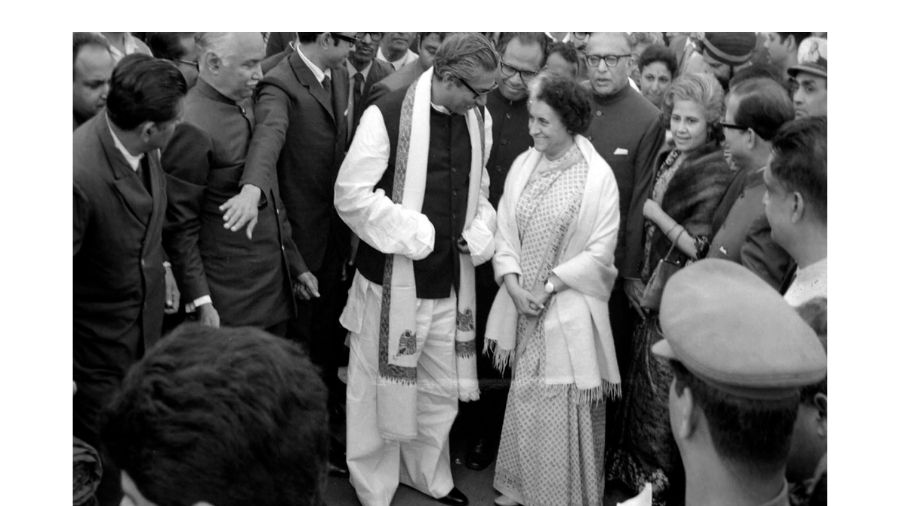

Indira Gandhi with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman The Telegraph archives

More specifically, he would like to see more special economic zones earmarked for India; joint economic activity by the two countries; development by both countries in concert of what he calls the “blue economy”, that is the exploitation in partnership of the ocean and sea-bed resources in their respective exclusive economic zones (I am reminded of one US sea-food entrepreneur telling me that “the Bay of Bengal is the only considerable body of water in the world where tuna die of old age”); and a determined increase in multimodal connectivity through Bangladesh into India’s North-East.

He stresses the joint harnessing of water resources in the North-East and Bangladesh, pointing out that 40 million of the poorest people in the world live in the corner of the subcontinent occupied by the North-East whose rapid economic progress is vital to ensuring sustained double-digit growth for India as a whole, and to the abundant opportunities this would open to a properly connected Bangladesh. This is music to my ears as I have served as India’s Minister for the Development of the North-East Region (DoNER, 2006-09) and attempted then to persuade both my own government and Bangladesh’s to take major initiatives in this regard but ran into MEA’s and our then HC’s adamant refusal to be seen as accommodating the Khaleda regime. Now, happily, the current Indian High Commissioner points out in his lecture cited above that:

“The World Bank estimates that better connectivity infrastructure – road, rail, land ports, inland water routes and dredging, container terminals and transshipment, ports and air services – will raise Bangladesh exports to India by nearly 190%, while Indian exports would also increase by 120%.”

He adds: “Simplification of cross-border transport regulations would in themselves lead to a significant increase in trade, which together would fuel a 19% increase in GDP growth in Bangladesh”.

Then why not do it? What is so difficult about simplifying regulations? One view is that Bangladesh goods are deliberately held up for unconscionably long at land borders because 40% of the West Bengal officials concerned are migrants from East Bengal seeking to avenge themselves for their displacement!

The Indian High Commissioner foresees a “300%” increase in Bangladesh exports to India if they would sign on to a “Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement”. If after all, “the two sides have also shown the will and the capacity to untie the Gordian knots of enclaves and border disputes on the eastern Radcliffe line”, and concluded a whole sheaf of agreements ranging from Farakka to Inland Water Trade and Transit to coastal shipping to railways, bus services, air flights and a robust energy partnership, besides border haats, what is the great difficulty in signing off on the proposed Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement? Perhaps the same reason for which the Modi government held back its hand on a similar agreement with South-east Asian economies: fear of outside domination of the domestic economy.

I am surprised at how downhearted former Bangladesh envoys to India sound. Says one, “The official spiel is a duplicitous spiel, masking real feelings”. The fact is, he adds, “we are India-locked”. That could either be a total blank wall or an incredible opportunity. There is a curious but telling difference in the remembrances of envoys of the two countries. While Indian envoys generally (but with significant exceptions) have fond memories of their tours of duty in Bangladesh – a reflection perhaps of the extraordinary warmth of hospitality that surrounds them in Dhaka (much as I felt in Karachi) – Bangladesh envoys seem to have experienced searing setbacks and unpleasant memories. Some of this, one explained, is “a spillover of history from a dead past to a live present”; some of it from the seeming intractability of bureaucratic ineptitude and lassitude they encountered in India. “We reach agreement at high-level meetings,” said one particularly successful High Commissioner, “and then nothing happens till the next annual round”.

Frankly, I am amazed. When I was in our Foreign Service, I was ordered by my bosses to hound my counterpart officers till decisions taken at a higher level were implemented on the ground; Bangladesh seems to find it impossible to do the same despite a full-fledged High Commission in Delhi and consulates everywhere, including, of course, Calcutta. Something somewhere has gone terribly wrong.

A leading footwear exporter complains of a consignment he sent on which he had to pay heavy demurrage because the Indian authorities said they had to check whether his shoes and chappals matched Indian standards although he was renowned in Japanese and Korean and western markets for the high quality of his products. They then sent his samples for testing at the Central Leather Research Institute in Chennai and smugly informed the Bangladeshi businessman that they did not know when his samples would be returned, and only then would the consignment be cleared.

“The Indian bureaucracy is overbearing and arrogant. We are not treated with respect” is one reason advanced. That may well be true, but the story seems to be written in similar letters in Bangladesh, where powerful ‘babudom’ famously stalled a determined effort to put up a CEAT tyre factory in Bangladesh. I offer a solution to both sides. Why not just bribe your way through as you are so successfully doing in your own country?

As of the Golden Jubilee of Liberation, there are three major stumbling blocks in the way of improving relations:

Communal tensions, which bring Hindu-Muslim issues to the fore instead of getting on with reaping the benefits of structural complementarities;

Border killings by India’s Border Security Forces, particularly focused on keeping the Indian cow from being slaughtered in Bangladesh and keeping out Bangladeshi immigrant “termites”, in Home Minister Amit Shah’s felicitous choice of words that has done more damage to our relations than the failed NRC exercise in Assam;

Non-signing of the negotiated and initialled Teesta water sharing and basin development agreement.

Let us consider each in turn.

Communalism

One badly wounded freedom fighter-turned-editor is blunt: “Modi is the biggest threat to Indo-Bangladesh relations”. He bemoans that “we never thought India would leave the secular path. Now, when Hasina tries to curtail communal extremism in Bangladesh, she won’t succeed unless India does its bit”. Another friend of India anxiously asks, “Is secularism on the way out in India?” A third says, “We can’t choose who will be in power in Delhi, but it is going to be a huge challenge for Bangladesh if things continue in India the way they are going.”

The bottom line is that majoritarianism in either country is the determinant of progress or deterioration of perceptions in Bangladesh of India, and vice versa. The pursuit of Hindutva, that is ‘Hindudom’ or Hindu raj in India, will inevitably stoke persecution of the minority in Bangladesh. That is why a shared conviction in “secularism” was what bound Bangabandhu and Indira Gandhi together as they led their respective forces to the War of Liberation. If secularism goes in either country, no number of high-level accords is going to keep the peace. The path to constructive cooperation is paved through communal harmony. All else will vanish if communal relations are not maintained on even keel. The ‘Golden Age’ rests on extremely fragile foundations and if these are fractured by rising religious intolerance towards the minority in either country, both will pay a heavy price. “We had come out of the Two Nation syndrome,” moans one expert who really does know both countries, “but it would be disingenuous to think we can remain secular on our own”.

Border Killings

“Bangladesh feels strongly about killings of Bangladesh citizens by Indian border security forces. The number may be small, but it keeps happening every day.” The indignation at this is widely shared. I heard similar complaints a decade ago. It seems outrageous that we have not found a solution in all these years. One friend of India’s asks that we understand that there are farmers in large numbers on lands abutting the border, sharecroppers who toil late into the night. Why shoot when experience has shown that your security forces cannot distinguish in the dark (or even in broad daylight) between Indian and Bangladeshi in the desperate attempt to stop cattle smugglers and human traffickers from crossing the border. Yes, punish them, certainly, if they are caught, but why shoot to kill? Why can we not have a strip of acceptable width at the border within which your security forces may patrol but without being armed? India, of course, has its own answers ready to all these questions, but polemics is no answer when the issue involves life itself and the need is to find a solution. A favourite Indian official argument is that “Indians too get killed.”

That is not a convincing argument. The point is that ordinary people of whatever nationality are being killed and that must not happen.

Teesta

Until the agreement negotiated and initialled a decade ago is signed, sealed and delivered, the issue will simmer and give those Bangladeshis who are not India’s well-wishers a popular platform to rouse anti-India feelings. Also, and perhaps more importantly, until the agreement is signed and ratified, we just cannot get on with jointly developing the river basins that our North-East and West Bengal share with Bangladesh.

This is to the serious detriment of both countries, but perhaps Bangladesh more as river pollution is threatening this quintessentially riverine land so seriously that one angry interlocutor predicts that so long as Bangladesh remains a global dumping ground for unwanted waste, the country will run out of unpolluted rivers by mid-century. On the other hand, river basin development, as agreed by Dr. Manmohan Singh and Sheikh Hasina twelve years ago, holds vast possibilities of dramatically improving the lives of the hundreds of millions of Indians and Bangladeshis who live in this shared region.

Everyone knows that Mamata is the stumbling block, but should she not be persuaded by the Government of India on a regular, confidential basis to yield rather than attempting to bully her into acquiescence by holding a pistol to her head on the eve of high-profile visits, when her agreeing will look as if she is succumbing to outside influence instead of manfully guarding West Bengal’s interests?

In closing, a remark of a former Bangladesh envoy of immense goodwill reverberates in my head, “We have another two years, no more”. With determination, that should do. Otherwise, even two decades will not be enough.

Concluded