One year after the Sheikh Hasina-led Awami League government was toppled, the enthusiasm of those seeking change in Bangladesh seems tempered and hopes recalibrated. There is a loss of faith in the interim government but, at the same time, a refusal to go back to the Awami League. And hope, but no real conviction.

“We want institutional and systemic change. But now, the interim government is mirroring what has happened before,” says Asim Hossain, who took part in the demonstrations in 2024. “In fact, in the online space, there is an attempt to create a binary, to vilify the progressives as Shahbagis [after the Shahbag uprising against war criminals of 1971] and the fundamentalists as Shaplas [a reminder of a crackdown on Islamist groups]. It’s a dangerous binary.”

Israt Jahan Shawon, another student, says: “I am pessimistic. The government has changed. But can you change people’s mindsets?”

Speaking from New York, Kazi Farzana Shoily, a researcher dealing with social movements of East Pakistan in the 1950s and ’60s, blends cautious optimism and wariness.

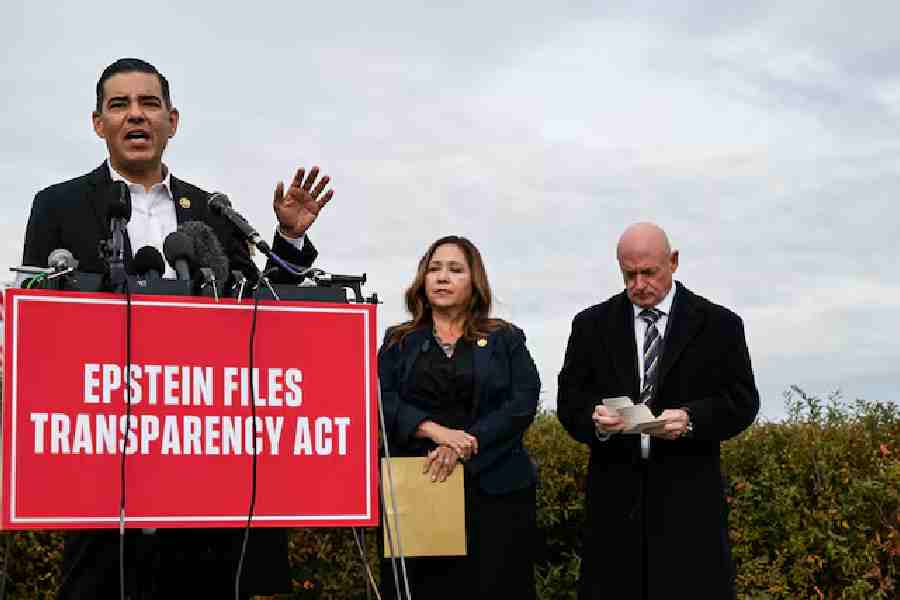

Protesters try to demolish a large statue of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, father of Bangladesh leader Sheikh Hasina, after she resigned as Prime Minister, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Monday, Aug. 5, 2024. (AP/PTI)

“It is a confusing moment for commenting on Bangladesh,” she says. “Being in Dhaka on August 5, 2024, I was hopeful. But it has increasingly become a situation dominated by random violence. In the last 12 months, we have seen many videos on social media of people being murdered in the streets, and we don’t know what the future holds.”

The students say that the violence in the streets has escalated along with moral policing and the stigmatisation of minorities.

On August 8, the day Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus, chief advisor to the interim government, announced the election dates for February 2026, Sheikh Hasina, the deposed Bangladesh prime minister who has been in Delhi since fleeing the country last year, submitted an urgent action to the UN Independent Expert on the Promotion of a Democratic International Order through her lawyers.

Not only has her party been banned since May 2025, all activities of the party have also been restricted until the conclusion of proceedings of the Bangladesh International Crimes Tribunal against Awami leaders, including Hasina.

“It’s a kangaroo court,” Obaidul Quader, a former general secretary of the party and a member of parliament, says dismissively.

Despite Quader’s dismissal, within a year of the uprising the revamped political landscape of Bangladesh has excluded his party from the electoral equation. The Awami League was banned by the country's election commission in May 2025

“The interim government’s ban on all activities of the Awami League inherent to the functioning of a political party, including public communication, gatherings, and its registration, mirrors the repressive tactics that were used by the very regime it claims to reject,” Smriti Singh, South Asia regional director of Amnesty International, tells The Telegraph Online.

What does the election mean for Bangladesh?

Yunus considers the upcoming election “the final and most important chapter of the interim government’s tenure” following the mass uprising in July 2024. The election, he says, will initiate the process of handing over responsibilities to a democratically elected government.

“Yunus’s political administration is judged from multiple levels — locally, nationally, internationally. While some sections see influence of the West in his administration, others find hope in the fact that they can question his policies and practice freedom of speech. The announcement of election is a resurgence of some hope,” Farzana says.

Ifti Nihal, who is with @the.bideshi, an online community, believes that this is the closest Bangladesh has been to true democracy in the last 15 years.

“For young people regardless of the outcome, this may be their first vote that actually counts. That’s special. A disappointing truth, but special, nonetheless,” he tells The Telegraph Online from Florida, where he is based.

“Again, the situation isn’t perfect, but if the interim government can carry out a fair and free election, it will be one of the greatest achievements by any Bangladeshi government this century."

Quader, unsurprisingly, feels the elections will be obantor (meaningless). He is also not sure that the elections will eventually happen. “In a situation of Awami League’s rising popularity, with the ban in place, the polls won’t be inclusive if it’s held. People are rethinking what we have lost after losing Sheikh Hasina.”

The claim of popularity, however, takes a big hit when facts are checked. The UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights report published in February accused the former Awami League government of Bangladesh of killing 1,400 people. Understandably, there is still anger against Hasina and her regime.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, an Awami League politician says that the situation in Bangladesh is “very complicated” at the moment, while admitting that Hasina was led up the wrong path by her advisors with their business interests: “The last election was not an appropriate election. Awami League vs Awami League is an unheard-of situation. She started playing this game, which was suicidal.”

The main political options in Bangladesh over the last 55 years were Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Currently the BNP is the main alternative. A distant second is the Jamaat-e-Islami, the group that opposed Bangladesh’s liberation from Pakistan in 1971.

Over the last year, skeletons from the Awami League's closet have tumbled out, and the brutality of Hasina’s regime has been exposed. There has also been criticism of the transition period under Yunus.

On July 30 this year, Human Rights Watch took note of the positive steps taken by the interim government to bring back a sense of normalcy, but at the same time documented a long list of violations that needed urgent attention.

“Everyone you ask in Bangladesh will say the same thing: it’s a whirlpool, and no one knows what will happen,” the Awami League politician says. The politician stresses that “firstly, there is no leadership right now; secondly, a state must be run by elected people who must be accountable to the people; thirdly, the current government is being managed, not run but managed, by some NGO people and some bureaucrats and some academics”.

During the July 2024 uprising, 21-year-old undergraduate student Ishmam Zaman stood in the streets with thousands of others. He was both participating in and witnessing a pivotal moment in his country's history.

Ishmam, who grew up in an Awami League-supporting family, was there chanting slogans in Bangla: “Tumi ke, ami ke/ Razakar, Razakar/Ke boleche, ke boleche/Shoirachar, shoirachar” (Who are you, who am I/Traitor, traitor/Says who, says who/The dictator, the dictator).

“Razakar implies people who collaborated with the Pakistani regime, which we fought for our liberation in 1971,” the young student tells The Telegraph Online. “Basically traitors. I hate the word Razakar. But we did this to counter the dehumanisation tactics of the Hasina government who were trying to call us traitors since we were protesting."

What began as a student protest against quotas transformed into one of Bangladesh’s largest people’s movements.

“It galvanised different interest groups. Everyone saw their chance. Many jumped into the fray with their own political interest to take power. The political groups fuelled the flames and the movement gathered a momentum of its own,” says undergrad student Shuzosh Rahman, a friend of Ishmam.

Mujib, Father of the Nation no longer

In Bangladesh, the interim government has implemented changes that could alter the way one sees the nation’s past.

The National Freedom Fighter’s Council Act has been changed, altering the definition of a freedom fighter, and the “Father of the Nation” status bestowed upon Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was dropped in June this year.

Earlier in January, school textbooks were tweaked, and the name of Ziaur Rahman — a military officer who was Bangladesh's President from 1977 to 1981 — replaced Mujib’s name as the one to have declared liberation from Pakistan in 1971. Mujib’s face has been removed from the new bank notes.

“This interim government is trying to obliterate 1971. Or the 1952 language movement. Our history is gone. They only talk about 1947, the two-nation theory, and 2024 July. Mujib is still a unifying force, and the Awami League’s strength is the common people, but the spread of fundamentalism among the middle class is immense. It’s also a deep state issue. Both the US and China have interests in Bangladesh,” the Awami politician says.

Ishmam, who was part of the student uprising, asserts, “For Awami to have any hope of revival, it must work without Hasina. While we may criticise the events of the Yunus period, this should not be interpreted as support for Hasina.”

On August 6, Yunus read out the July Declaration that would recognise those who participated in the 2024 uprising as national heroes, who would be given legal protection.

More than anything else, for Bangladesh, it appears that there is an opportunity to celebrate the uprising in 2024 that toppled a brutal regime and move forward towards newer coordinates. With or without the Awami League playing a role in it.