Many Iranians are not going to American universities this fall. Students from Afghanistan are having trouble getting to campus.

Even students from China and India, the top two senders of international students to the United States, have been flummoxed by a maze of new obstacles the Trump administration has set up to slow or deter people entering the country from abroad.

Between the federal government’s heightened vetting of student visas and President Trump’s travel ban, the number of international students newly enrolled in American universities seems certain to drop — by a lot.

There were about a million international students studying in the United States a year ago, according to figures published by the State Department. Data on international student enrollment is not expected to be released until the fall. But higher education is already feeling the pain and deeply worried about the fallout.

Many schools have seen the number of international students grow in recent years. But a survey of over 500 colleges and universities by the Institute of International Education, a nonprofit which works with governments and others to promote international education, found that 35 percent of the schools experienced a dip in applications from abroad last spring, the most since the pandemic.

In China and India, there have been few visa appointments available for students in recent months, and sometimes none at all, according to the Association of International Educators, also known as NAFSA, a professional organization. If visa problems persist, new international student enrollment in American colleges could drop by 30 to 40 percent overall this fall, a loss of 150,000 students, according to the group’s analysis.

Some students have given up on enrolling in U.S. schools entirely out of anxiety over the political environment in the United States. Others are staying away because they worry that even if they were to gain entry, they would effectively be trapped, unable to do things that other students can, like apply for internships or travel home over the holidays to see their families.

International students make up a significant portion of enrollment at elite universities like Columbia, but also at public institutions like Purdue. At Arizona State University, one of the ten universities that enroll the most international students, the number beginning their studies this fall — 14,600 in all — is down by about 500 from last fall, a spokesman said, mostly because of visa delays.

Many international students pay full tuition and are a revenue source that schools have come to rely on, including to help underwrite financial aid for other students. It’s part of the business model.

Wendy Wolford, vice provost for international affairs at Cornell University, said the biggest loss from the drop in international enrollment is talent.

“They’re literally some of the best in the world,” she said.

Ms. Wolford said she was also worried about the lost opportunity for domestic students to be exposed to students from different cultures, and for international students to spread good will toward the United States when they return home.

The Trump administration began focusing on international students last spring, taking a number of steps to target students who were already in the country and to increase vetting of those who wanted to enroll.

While President Trump said that he welcomed international students, he argued that some of them pose security risks and may be involved in academic espionage. He also said foreign students were taking up coveted slots at universities that could instead go to American citizens.

“We have people who want to go to Harvard and other schools, they can’t get in because we have foreign students there,” Mr. Trump said. “But I want to make sure that the foreign students are people that can love our country.”

In one of its first moves, the Trump administration threatened to deport more than 1,800 international students studying in the United States. In many cases, the reasons were opaque.

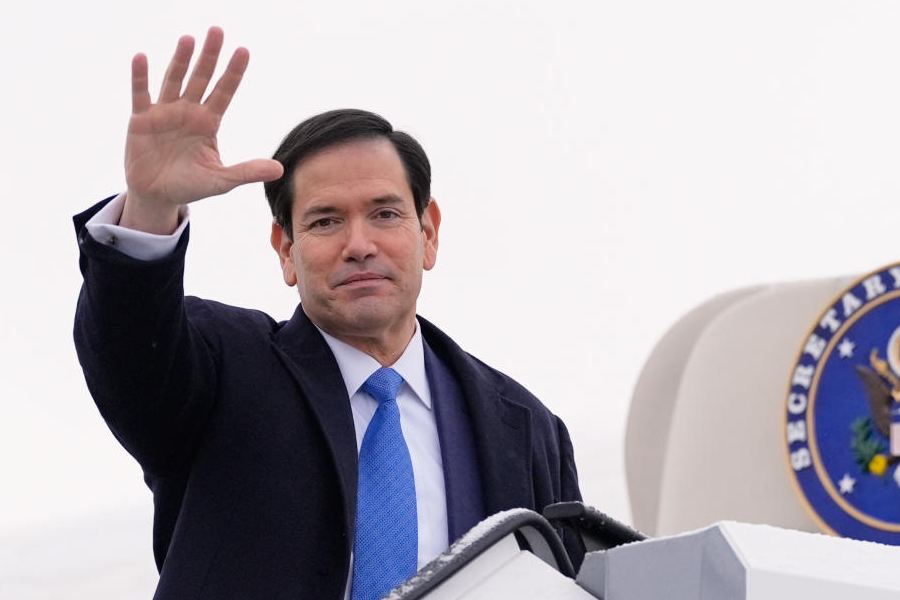

Secretary of State Marco Rubio has said that international students who were a part of campus protests over the war in Gaza, in particular, were not welcome. “We gave you a visa to come and study and get a degree,” he said last spring, “not to become a social activist that tears up our university campuses.”

Several groups have gone to court to challenge what they called an ideological deportation policy. Veena Dubal, general counsel for the American Association of University Professors, says the administration is violating the constitutional rights of noncitizens and citizens alike in choosing to deport people based on views that are protected by the First Amendment.

Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, has argued that the crackdown is undemocratic. “This practice is one we’d ordinarily associate with the most repressive political regimes,” he has said.

After an outcry, many of the students targeted for deportation were reinstated. But overall this year, State Department officials said they have revoked more than 6,000 student visas, on grounds of supporting terrorism, overstaying visas and breaking the law, a number first reported by Fox News.

And the State Department suspended new student visa appointments between May 27 and June 18, a time of year that is ordinarily the peak season.

When the government began issuing student visas again in late June, it was with a proviso that consulates would scrutinize applicants’ social media more rigorously. That has made the process much slower, and students who have yet to clear the interview process may be in danger of missing the start of fall classes or may even have to postpone enrollment by a semester or more.

“There does appear to be a heightened review of student visa applications,” said Ms. Dubal, adding: “Their social media are being reviewed for expression of pro-Palestinian sentiment or critiques of Trump’s foreign policy positions.”

Mr. Trump signed a proclamation in late May barring foreign students from entering the United States to attend Harvard, citing security concerns, but a judge has blocked the order from taking effect.

In June, Mr. Trump signed another proclamation to fully or partially restrict the entry of people from 19 countries, including Afghanistan, Haiti, Iran, Yemen, Cuba, Laos and Venezuela, and to increase scrutiny of people from other countries, to make sure that the people “do not intend to harm Americans or our national interests.”

Though the proclamation did not target students in particular, many students have been caught up in the travel restrictions.

“Because of the travel ban, it’s just not possible to get student visas from certain countries,” said Dan Berger, an immigration lawyer in Northampton, Mass. “A lot of Afghan women had been offered full scholarships in the U.S. and can’t get visas.”

Asked about delays, a State Department spokesperson said that the department had made its vetting of visa applicants more effective and more efficient. “But in every case, we will take the time necessary to ensure an applicant is eligible for the visa sought and does not pose a risk to the safety and security of the United States,” the spokesperson said.

Noushin, an Iranian student who was admitted to the University of South Carolina to study for a doctorate in chemical engineering, was caught up in the travel ban. She had a visa interview in September 2024 and was to start her studies in the spring of 2025, but she has yet to hear whether her visa will be approved. She is now helping to organize a lobbying campaign to end the visa delays, and says that a chat group on Telegram suggests that there are hundreds of other Iranian students in similar situations.

The New York Times Services