Boris Spassky, the world chess champion whose career was overshadowed by his loss to Bobby Fischer in the “Match of the Century” in 1972, died on Thursday in Moscow. He was 88.

His death was announced by the International Chess Federation, the game’s governing body, which did not cite a cause. Spassky had suffered a major stroke in 2010 that left him in a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Arkady Dvorkovich, the president of the federation, said in a statement: “He was not only one of the greatest players of the Soviet era and the world, but also a true gentleman. His contributions to chess will never be forgotten.”

Spassky had noteworthy accomplishments as a player, but the politics of the match with Fischer, at the height of the Cold War, and the media attention focused on it, turned both of them into pawns in a wider drama.

Spassky was not happy about all the attention. In a 2023 interview for an exhibition at the World Chess Hall of Fame in St Louis, his son, Boris Jr, said: “The role that he played in the 1972 match, he always thought of it as a chess player, because all the fuss around it, political, geostrategic, he never mentioned it. I am pretty certain that he felt the pressure.”

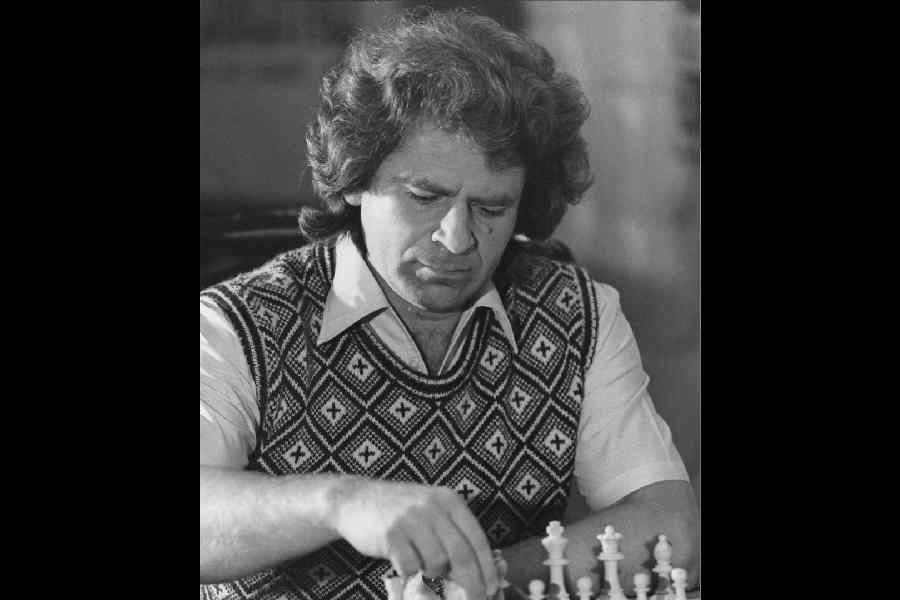

Russian chess player Boris Spassky in Geneva on 22 August 1977.

It was a measure of the match’s resonance that 20 years later, when the two men staged a rematch, it drew worldwide interest, even though both players were well past their prime.

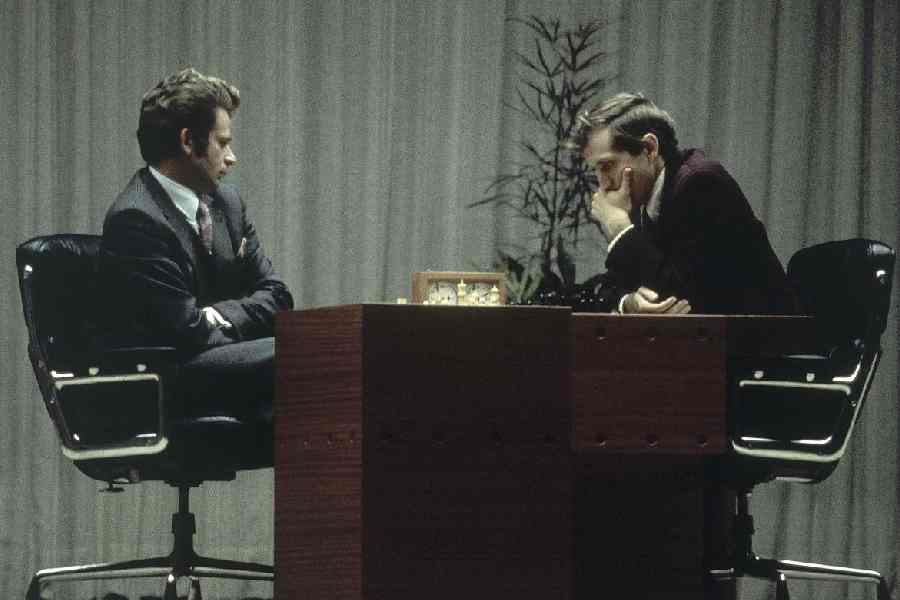

When they played the first match, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Fischer, with his brash personality, was something of a folk hero in the West.

Fischer was widely portrayed as a lone gunslinger boldly taking on the might of the Soviet chess machine, with Spassky representing the repressive Soviet empire.

The reality could not have been further from the truth. Fischer was a spoiled 29-year-old man-child, often irascible and difficult. Spassky, at 35, was urbane, laid back and good-natured, acceding to Fischer’s many demands leading up to and during the match.

The match almost did not happen. It was supposed to start on July 2, but Fischer was still in New York, demanding more money for both players. A British promoter, James Slater, added $125,000 to the prize fund, which doubled it to $250,000 (about $1.9 million today), and Fischer arrived on July 4.

The match was a best-of-24 series, with each win counting as one point, each draw as a half point and each loss as zero. The first player to 12.5 points would be the winner.

In Game 1, on July 11, Fischer blundered and lost. Afterwards, he refused to play Game 2 unless the television cameras recording the match were turned off. When they were not, Fischer forfeited the game.

The match seemed in doubt, but a compromise was worked out to move the match to a tiny, closed playing area behind the main hall.

Fischer won Game 3, his first victory ever against Spassky, and proceeded to steamroll him, winning the match 12.5 to 8.5.

Spassky’s sportsmanship was on full display in Game 6 of the match, which by then had been moved back into the main hall. When Fischer won the game, taking the lead for the first time in the match, Spassky joined with the spectators in standing and applauding his victory.

After losing the match, Spassky received a chilly reception on his return to the Soviet Union. He bounced back to win the Soviet Championship in 1973 and reached the semifinals of the qualifying matches for the world championship in 1974, losing to Anatoly Karpov, the future world champion.

Still, things were not the same. For two years, he was banned from travelling abroad, the lifeblood of a professional chess player in the Soviet Union, and his financial support and perks were cut. He found a way out, however.

In 1975, he met Marina Stcherbatcheff, a secretary working at the French embassy in Moscow, who became his third wife. They moved to France, and he became a French citizen in 1978.

In 2012, in a bizarre episode, Spassky was whisked out of France, turning up about a month later in Russia, where he claimed that he had been kept against his will in a hospital in France and had been able to leave only with help from friends.

He lived in Moscow for the rest of his life.

The pressure that Spassky felt to defend the Soviet hegemony over chess was immense. Years later, he was reported to have said of the 1972 match: “I was happy to lose the championship. My years as champion were the worst years of my life.”

By 1992, Spassky was living on the margins of the chess world. Then the owner of a bank in Belgrade, where Fischer was living, offered $5 million for a return match with Fischer.

The condition was that the match would be played in Serbia and Montenegro, the former Yugoslavia, which were under UN sanctions for waging a brutal war againstCroatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The match violated the sanctions, but Spassky enthusiastically agreed to play. “He pulls me out of oblivion,” he said of Fischer. “He makes me fight. It’s a miracle and I am grateful.”

The match received worldwide attention and lasted 30 games, but the result wasno different from the one 20 years earlier: Fischer won, 10 games to 5, with draws not counting.

The matches differed, however, in two respects: The quality of play had suffered a sharp decline, and the tension between the two players was gone. Spassky and Fischer, bound together by being at the centre of so much scrutiny for so long, were old friends, laughing and talking before and after the games.

New York Times News Service