Bengali to Polish to Urdu, idiom to poetry to translation - a peek at some sessions at Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet 2015, in association With Victoria Memorial Hall and The Telegraph

Language no bar

The future of Bengali is what two practitioners and a chronicler of the language sat down to discuss on Day 2 of the literary meet.

But the talk began with a scrutiny of the present usage of words in different strata of society and differences in conversation styles. 'Amid the lower registers of Bengali, we still find words that are not included in the dictionary. Some of these words, dismissed as obscene, have innocent usage in rural Bengali. There is nothing objectionable about Amar pnode pnode ghurish na (Don't stick to my bum and follow me around),' said author Swapnamoy Chakraborty, arguing that no words were obscene, their usage was. 'There is no need to disrespect slang. Terms like 'tube light' to mean dim-witted have humour ingrained in them.'

Chandril Bhattacharya of Chandrabindoo was introduced by moderator Jayanta Sengupta, the secretary-curator of Victoria Memorial, as a popular cultural icon who has introduced a new kind of language like Kaliprasanna Sinha had in Hutom Pnyachar Naksha. 'The only similarity I have with Hutom is in attitude,' retorted Chandril, a journalist with Anandabazar Patrika.

(From left) Gautam Bhadra, Jayanta Sengupta, Swapnamoy Chakraborty and Chandril Bhattacharya

As for his own popularity among the youth, while admitting that the youth were iconoclast in any society, Chandril added that he was deeply suspicious of their appreciation. 'Perhaps they think it is fashionable to declare a liking for my writing because others are saying so.' He went on to pillory the attitude of the urban youth towards their mother-tongue. 'Try placing an order in Bengali instead of English in a restaurant or a shopping mall. The day is not far when wearing panjabi would be banned on Park Street,' he said, voice dripping with sarcasm.

Talking about how Hindi idiom was affecting Bengali, Chandril cited: 'When someone says Kan khule shune ne amar cheye kharap keu hobe na, it is more Hindi than Bengali.' Bengali advertisements, too, were increasingly falling prey to mindless translation, he pointed out. 'I use words from other languages like bindaas but I appropriate the word within the structure and meaning of a Bengali sentence.'

Countering Chandril's contention that guruchandali (juxtaposing words from different registers of a language) is in, philologist Gautam Bhadra asserted the practice was prevalent even in the time of Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay. 'Look at Kamalakanter Daptar or Lokrahasya. How can a language exist without guruchandali? How else will it find a balance?' he said, adding that he welcomed the multi-lingual parlance of the youth. 'A language evolves not just vertically down the ages but also horizontally by drawing from other contemporary languages.'

Poetry sans border

'Sometimes you can listen to poetry in a language that you don't understand and still have a wonderful experience,' said Julia Fiedorczuk, one of the three Polish poets in conversation on Day 3.

For all three - Fiedorczuk, Jerzy Jarniewicz and Dariusz Sosnicki - poetry is more than just a form of self-expression. In poetry, one can 'find the history of the language and the history of the country', said Sosnicki, who read out a translation of his poem Monster, a haunting piece about a train travelling across the plains of Poland.

For Jarniewicz, poetry should address 'the suffering, not of an individual, but of a community'. What makes her stand relevant is the turbulent modern history of Poland.

Manto matters

Ayesha Jalal, grandniece of Saadat Hasan Manto, and Aakar Patel, a journalist who has translated the Urdu poet's essays, came together to discuss Manto's oeuvre on Day 3.

Ayesha Jalal

Patel discovered Manto at age 13, when he stumbled upon Bu in Debonair. His 'hair stood on end when he realised that 'sex could be written in an Indian way''. It was only in his twenties though that Patel really unearthed the depth of Manto's work, which led to years of obsessive reading before he took to translating Manto.

Jalal pointed out that though Manto was put on trial for his works, he was never indicted, which is proof that some open-mindedness did exist. Manto saw himself as a 'vehicle of perception of society'. He objected to being accused of misogyny and obscenity when, in reality, his characters were reflections of people he had observed. 'That's Manto for you,' his grandniece pointed out. 'He touched upon subjects that were awkward to talk about.'

Are we reading Manto wrong? Jalal seems to think so. Even though the cultural nation in Manto's works is more expansive than the political nation, his readers continue to try to read him through the 'prisms of those nationalisms that he rejected'. The truth is he cannot be limited to either a religious or a secular nationalism. But the happy truth is that misinterpreted or not, Manto continues to be read. Jalal believes the poet is alive because of lack of state sponsorship and, as long as there is opposition, he will flourish.

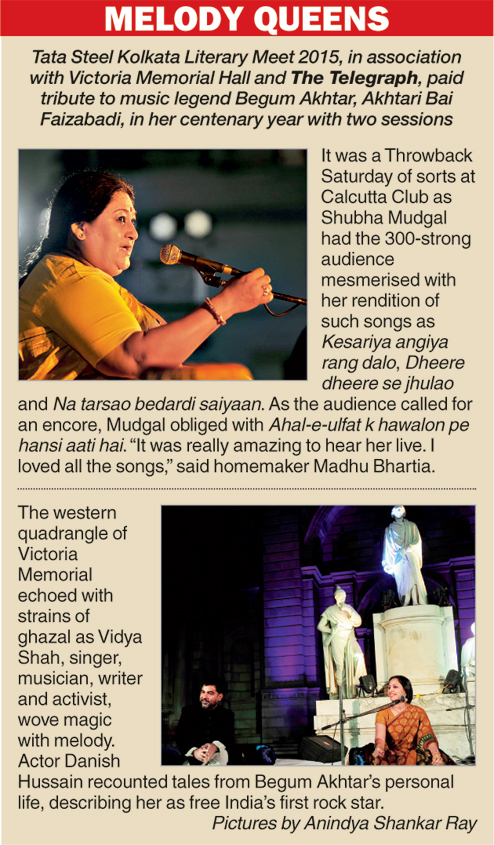

Pictures by Anindya Shankar Ray and B. Halder