|

Not everyone who works at Lalbazar is a cop. That was my first lesson as I roamed the corridors of power in an attempt to know a little more about the historic building that houses the headquarters of the city police. I had imagined bright, long corridors with serious-looking policemen briskly going about their business of protecting the city and cracking difficult cases.

But I found out that policing is as much about gun-toting cops in smart uniforms as meticulous, painstaking — and often unrewarding — paperwork and research, carried out by government officials who do not enjoy the distinction of being cops but are an inseparable part of protecting the city.

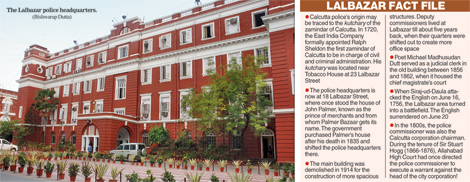

The first glimpse of Lalbazar from the inside is impressive. Four tall buildings painted a crisp red and white stand facing each other, enclosing a courtyard. Mostly white (and some red) police vehicles dot the courtyard and leafy trees provide green relief. Some of the upper floors have bougainvilleas sprouting from the balconies.

Opinion is divided about the origin of the name Lalbazar. Some say the reflection of the red Old Fort William (which stood where the GPO stands today) on the water of the tank led to the name Laldighi. And thus the nearby area came to be called Lalbazar. Another legend holds that Indians started calling the area Lalbazar because it was occupied and controlled by pink-complexioned Europeans only.

Whatever the reason, one assumes the Left Front government was mighty pleased with the nomenclature when it came to power in 1977!

Of the four buildings at Lalbazar today, the south wing houses the administrative section, the north wing the control room, the east wing has the traffic department and the west wing the detective department.

The detective department had been set up by Sir Stuart Hogg following the murder of an alleged prostitute, Rose Brown, on April 1, 1868, on the pavement of Amherst Street. And I thought this guy only gave us Hogg Market (New Market that is)! The fledgling detective department had one inspector, four darogas, 10 head constables, 10 second-grade and 10 third-grade constables, all headed by a superintendent.

Led by joint commissioner Damayanti Sen, the number of squads, cells, sections and bureaus that make up the department now boggles — and reassures — the mind. There’s the homicide squad, dacoity and robbery squad, antique theft squad, fraud section, cyber crime cell, environmental cell, anti-rowdy squad, women’s grievance cell, missing person’s squad, dog squad, bomb squad, anti-terrorist cell and the criminal record section, to name just a few. Phew!

My first stop was the office of police commissioner R.K. Pachnanda. Thump, thump, my heart was already travelling towards my throat. What would I say to the senior-most officer of the city police force? What if he thought I was wasting his time? Why do I get myself into these situations!

I needn’t have fretted at all. When I told the police chief that I wished to write about the Lalbazar building, he was so enthusiastic that I forgot my tongue-tied self and sat merrily chatting about the history of the police force. On the wall behind the commissioner’s chair hangs portraits of Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda. Below them is the white and navy blue flag of Calcutta police. On two walls are pictures of all the police commissioners of the force, right from S. Wauchope, who became the first commissioner of police in November 1856 to the infamous Charles Tegart (1923-31) and the first Indian commissioner S.N. Chatarji, who assumed office on August 15, 1947, to the modern-day incumbents.

One corner of the room is decorated with three helmets, one white and two navy blue. I was thoroughly intrigued to learn that while the white one belongs to Calcutta police, the other two bear the insignia of Thames Valley police and Northamptonshire police. “They must have been token gifts from visiting officers from these forces,” explained the top cop.

Taking his leave, I went on a guided tour of the buildings. My guide was inspector Soven Banerjee, who is compiling a history of Lalbazar.

The insides of the buildings are much like any old government office, with files stacked right up to the tall ceilings, spacious staircases worn out under decades of passing feet, old curtains in need of a wash, simple office furniture and a dinosaur-aged lift. But as I passed by the entrance of the police control room (they, of course, didn’t let me in), I spotted a sleek electronic lock embedded into the whitewashed wall, much like the ones you would have seen on CSI on STAR World. I was impressed.

Inspector Banerjee explained to me what happens when the control room receives an alert. The OC (control) relays the message to the joint commissioner (headquarters) or the commissioner, depending on the importance. Then the movement cell springs into action and sends instructions and forces. There’s always a team at Lalbazar ready to be deployed in under five minutes of receiving an alert. I recalled seeing a picture in the commissioner’s room of this ready-to-be-deployed force in pre-Independence times, captioned “Ready to fly”.

The four buildings are four storeys high, above which is the roof. Is the roof accessible, I asked. Inspector Banerjee contacted the office of OC (Buildings), whose department is responsible for the maintenance of Lalbazar along with the public works department, and up we went through a spiralling stairwell that reminded me of my Shahid Minar climb.

“It may be just four storeys high but these old buildings are as tall as eight floors of our modern highrises,” remarked my tour guide, soothing my huffing-puffing ego. The parapet is almost one human-high, which meant I didn’t get too good a view of the surroundings. But standing atop the very nerve centre of the city police force, I felt a heady rush — was it the height or the trappings of power”?

Samhita