|

|

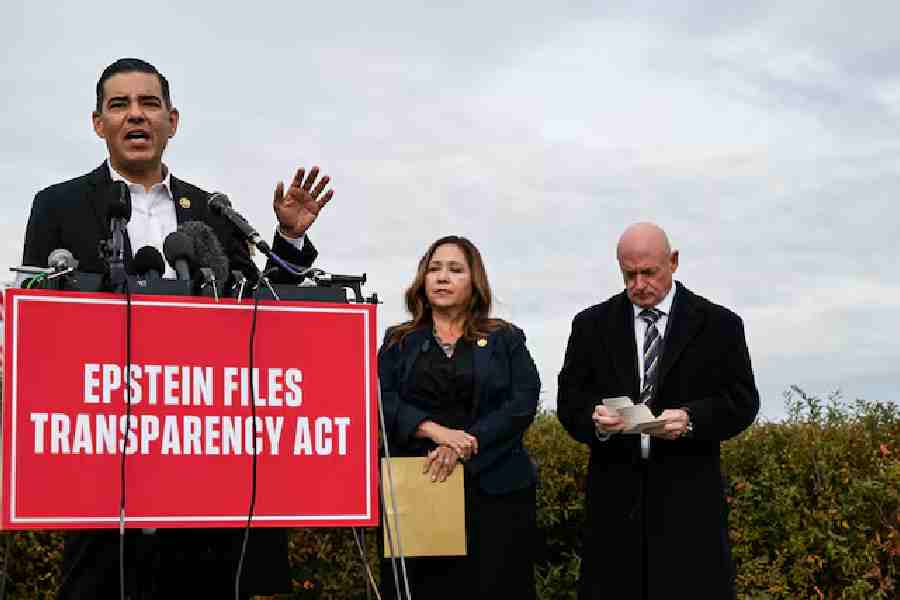

| (From top): Clive house on the mound as it used to look earlier; The restored sections flaunt a brand-new look |

Governor Gopal Krishna Gandhi, in his address to a recent workshop on Dalhousie Square, had made his views known on conservation and restoration.

To quote him verbatim: ?We Indians cherish our history, but neglect our heritage. We commemorate, we do not conserve. We substitute the responsibility of caring with the exhilaration of celebrating. We decorate where we should restore, we ?beautify? where plain cleaning is called for, preferring to renovate, refurbish, rename and even to replace rather than repair, renew, restore.?

It would be advisable for anybody carrying out a conservation project to remember these words, for this city itself has witnessed many travesties of such undertakings.

The Raja Rammohun Roy residence on the street named after him is a glaring example.

Another is the group of columns of the Sabarna Choudhury aatchala in Barisha, rebuilt of late.

And look at those horrendous ?old-world? lamp posts planted of late under the Park Street flyover. These were surely inspired by Bollywood productions aimed at locating Sarat Chandra novels in cloud cuckoo land.

So, those who feel strongly about the need to preserve and conserve our heritage, even if it happens to be linked with a rather embarrassing chapter of our history, must have been pleased when the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) declared in 2003 that it will take over the dilapidated Clive house in Dum Dum, Hastings? equally derelict building in Barasat, the man-made ruins of Currency Building in Dalhousie Square and the two synagogues in the city.

People in this state still feel very strongly about both Clive and Hastings and, in a way, hold them personally responsible for their subjugation for 200 years. Opinions were divided over whether Clive house should be restored at all, particularly when no help was forthcoming from the British government.

But what is known as Clive house predated the man who helped establish British rule in India. It was, in fact, an overlay of structures. Even about 10 years ago, it was in fairly good shape and the roof was intact, though spongy. Some monsoons later, its only roof was the open sky.

The core of the building was piled high with debris that hang loose and the beautiful columns looked wobbly.

It was already overgrown with huge trees. Squatters ? about 20 to 25 families in all ? had occupied the rooms and the peripheries of the building from Partition. Braving chunks of hurtling masonry, they are still there, although officially the building belongs to the ASI. Yet, Clive house, built on the mound that has of late yielded the remains of a township several centuries old, looked terribly romantic.

Now, depending partly on conjecture and partly on the structure revealed after clearing away the debris, the ASI has made an effort to ?restore? the unoccupied portion. So, while the windows on the side facing the playground have been sealed with tin sheets, and water still falls in spurts from a pipe attached to an occupied chamber, the ?restored? section looks brand new. It has the unreality of a film set.

Bimal Bandopadhyay, superintending archaeologist, ASI, Calcutta Circle, says work on the western side walls was taken up first as they could have collapsed on the shanties around the building.

The deep-rooted trees were removed and the huge mass of debris on the southern side was cleared. After removing the debris blocking the northern side, a semi-circular stairway leading to the arched opening was discovered.

The pillared verandah in a precarious state was consolidated. Some stairways were restored but the main staircase on the north-western side remains untouched.

?Work is hampered by the existence of the families. The government as well as the municipality have issued vacation notices but the occupants claim rehabilitation,? says Bandopadhyay. He fears that if there is any accident, they will pin the blame on the ASI.

He expects work to be completed in two years? time and would like to turn the building into a museum where the artefacts discovered under the mound will be displayed.