|

At one time, a veil of secrecy swathed No. 85 Park Street opposite St. Xavier’s College. Gradually the two huge gates disappeared, and now the crumbling, sprawling building at the far end of the lawn has lost its mystique and is exposed to the public gaze. The Murshidabad estate was once the seat of the descendants of Nawab Nazir Mir Zafar Mirza, the first puppet ruler of the British who in Bengal is still the archetype of treachery. Wasif Ali Mirza was the second and last nawab of Murshidabad. The property now belongs to the Bengal government and has been in status quo for over a century.

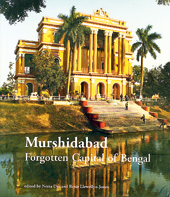

The miserable condition of the Murshidabad estate reflects the mess that the last independent capital of Bengal is in today. Murshidabad has some parallels with Calcutta. Murshidabad rose when the capital of Bengal shifted to that city from Dhaka. Murshidabad was eclipsed by Calcutta once it was declared the capital of British India. But Calcutta lost its primacy to Delhi once the capital shifted in 1911, when Calcutta’s decline began. Marg’s wonderful new book, Murshidabad: Forgotten Capital of Bengal, edited by historian Rosie Llewellyn-Jones and conservation architect Neeta Das, presents a holistic view of the city that has lent its name to the densely-populated district adjacent to the Bangladesh border, Sahebganj and and Pakur districts in Jharkhand and Burdwan and Birbhum in Bengal. The Bhagirathi river runs through it.

With contributors like Pratapaditya Pal, Jerry Losty and Llewellyn-Jones, who are well known in their field, the text is highly readable and comprehensive. The recent photographs, which complement the views in the old paintings, miniature and otherwise, add to the delight of thumbing this slim and informative volume. Llewellyn-Jones reveals that Murshid Quli Khan, after whom the city was named, was a convert, probably from Odisha. Such facts may be known to students of history but not many laypersons would be aware of this. However, Indians may have a problem with her unqualified acceptance of the British version of the Black Hole episode as a historical fact, particularly after Partha Chatterjee’s insightful The Black Hole of Power: History of a Global Practice of Power. As we know, it is not a matter of taking sides any longer.

Her essay on the palaces and pleasances of the city is highly informative, the accompanying building plans, photographs and illustrations making it even more interesting. Rajib Doogar’s excellent essay on the Jains of Murshidabad once again underlines the fact that in this country, even during Moghul rule these merchant princes held the purse strings. They still do. Neeta Das’s essay on religious buildings gives us a clear idea of the cosmopolitan nature of Murshidabad. The Armenians, Dutch and Portuguese, not to speak of the British were all there. Their houses of worship and cemeteries testify to their presence.

|

| RD Burman has found a permanent place in Calcutta, close to 36/1 South End Park where he spent his childhood. A half-bust statue of the composer was installed at the initiative of the Amit Kumar Fan Club and unveiled by Amit Kumar on Pancham’s 20th death anniversary. Usha Uthup and Indranil Sen were among those present. Picture by Arnab Mondal |

Jasleen Dhamija’s essay on textiles could have been a little more detailed, although Jerry Losty’s study of Murshidabad paintings more than makes up for it. These artists had been exposed to the contemporary art of the West, and they changed their style according to the tastes of their clientele. Not all these paintings were great works of art, but the reader gets the picture, so to speak, on viewing them. Murshidabad could have been Matiabruz considering the showy Muharram “mournings” (can this observance be termed a “festival” as the caption does?) and tolerance of Hindu festivals. Pratapaditya Pal’s essay on a particular Durga tableau carved out of ivory is a good example of how scholarship can throw light on a socio-cultural conundrum. In her concluding piece on present-day Murshidabad, Neeta Das justifiably voices her concern about the poor condition of the built heritage and the once-famous crafts which are all but forgotten. The Danes have come to the rescue of Serampore. Perhaps the heritage commission will wake up from its slumber. This book may help.

CINI milestone

Babu Dey was brought to CINI’s Sealdah centre from a nearby slum and admitted to a school but he couldn’t cope with studies. It was then decided that he would be sent off for vocational training to another city. But Babu didn’t want to leave Calcutta. He decided to work with slum children in and around Sealdah.

“One decision changed my life. Thank god CINI didn’t force me to leave the city. I’m still on the streets but now I’m helping thousands of helpless children,” said the child-beneficiary-turned-CINI employee at CINI’s 40th Foundation Day celebrations at Town Hall.

A book, Samir’s Choice — Forty Years of CINI Through the Life of its Founder, was released on the occasion. “The book is a collection of memories. CINI has been a long and fruitful journey,” Samir Chaudhuri said.

Contributed by Soumitra Das and Showli Chakraborty