April 17: Retired ship engineer George Nicholson's narration of the riverfront development in London and Calcutta is curiously titled "From Coin Street to Calcutta: A Tale of Two Pizza Restaurants".

That's because both riverfronts have a pizza restaurant. A thriving one on the South Bank at Gabriel's Wharf in London that speaks volumes about the success of public use of riverfront space and an old forlorn one called Scoop in Calcutta that stands at the Man-O-War jetty.

The state of the pizza restaurant in Calcutta is symptomatic of the riverfront development in the city, where initiatives happen in sudden spurts. Scoop was thriving during the 80s when planning for Millennium Park was in the works. But as the park came into being on another stretch in front of the Hooghly, Scoop lost its clientele as its portion of the riverfront stood derelict and forgotten.

Nicholson, who chaired the London Rivers Association (LRA) from 1987 till 2007, is going to make a presentation on the riverfront development in London and Calcutta at the London Festival of Architecture, scheduled for June.

As a member of the Greater London Council, Nicholson sees gaps in responsibility and policy-making both in London and Calcutta. "Town planning was always focussed on land use, and there was no policy on water space," he said. "The planning system was effectively blind to river development."

The London Rivers Association was created by the Greater London Council and local authorities to frame policies for water space management. "It took 40 years to develop the riverfront here," said Nicholson, chatting with Metro at Gabriel's Wharf on Good Friday afternoon.

A plaque to Ernie or John Hearn, a community activist who popularly went by that name, commemorates his struggle to keep the waterfront free of encroachment. A portion of the river still has the sandy beach with pebbles in front of Gabriel's Wharf where sand artists would create artwork, people ran their dogs and children built sand castles. Promenades on the South and North Banks of the Thames enable people to walk, jog and stroll around the waterfront.

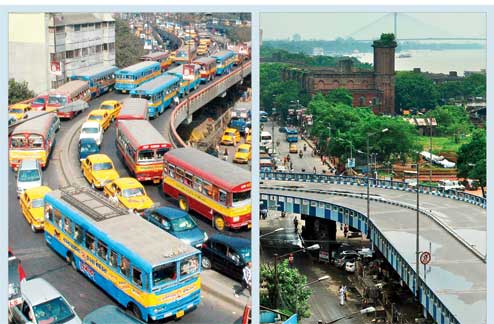

Cut back to Calcutta, where much of the riverside used to be walled in, denying people a direct view of the waterfront. "The riverfront was totally derelict and walled in when I visited Calcutta for the first time in 1987. The only public space was the Man-O-War jetty. The dock wall closed the river to the public," Nicholson recalled.

The then Left Front government revived old plans for riverfront development on either side of the Hooghly and asked Nicholson for his opinion. "Calcutta produced a plan drawn up in the 80s. Howrah had one as well. The Calcutta plan had an elevated flyover all the way over the waterfront, which I thought was absurd and told them so," Nicholson recounted. "We told them (the state government) to have a park on the waterfront. The millennium was approaching and they wanted a beautification project; so the park was created. I was surprised that it actually happened. There are too many stakeholders there," he said.

Millennium Park has since had two extensions - one to the south till Floatel, another from Fairlie Place to Howrah Bridge. "Now you need to stretch it up to the Mullickghat flower market," Nicholson recommended.

As for the warehouses along the river, Nicholson, whose presentation to the state government was titled "Development of Warehouses along the riverfront", told the local authorities to restore the colonial architecture of these buildings. "The Strand Warehouse was tragically gutted, but there are the Canning and Clive warehouses that can still be restored. These could well be restored as part of the development of Millennium Park. These warehouses were so well-built, they are still there," he said.

Nicholson's suggestions fall into place like a puzzle. Riverfront development always happens in bits and pieces fitting into a larger jigsaw. "The London riverfront has been developing for decades...Oxo Tower is an example of how old, derelict buildings can be adaptively reused. The Strand Road warehouses can be similarly reused," Nicholson said.

An example of adaptive reuse is, of course, London's defunct Bankside Power Station that now houses the Tate Modern.

But for Nicholson, the inspiration to make the river central to development came from Calcutta. "The concept of the river being holy made me start my campaign. Back then, all buildings had their back to the waterfront. Till the 70s, when you walked along London Bridge, all you saw were backyards. I started campaigning with the LRA and started to build a pro-river attitude. It took 10 years of campaigning and now prime residential property are all built river-facing," he said.