|

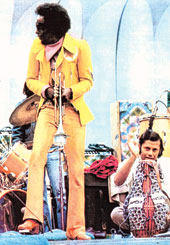

| All that jazz: (Above) Badal Roy (seated) with Miles Davis at a concert; (below) with Ornette Coleman |

|

This story has been recounted frequently enough in jazz circles, but it never ceases to amaze. In the summer of ’68, a young man from East Pakistan goes to New York to pursue a PhD in statistics. He takes up a job as a busboy in a fast-food joint to help pay college fees. To supplement his meagre income, he decides to make good use of his hobby of playing the tabla and teams up with a fellow countryman — who happens to play the sitar — and manages a slot for regular evening gigs at Taste of India, an Indian restaurant at Greenwich Village.

It’s a heady atmosphere: in the decade of peace, free love and Vietnam, and to a West seeking salvation in all things Indian, patrons simply can’t have enough of the tabla-sitar duo. Quite a number of them, in fact, become regulars, taken in by the raaga-roti combo.

One of the regulars, a young man with a quicksilver touch on the guitar, is so enthralled by the music that he even starts performing with the duo, though not regularly. After jamming with them for about six months, he asks the tabla player whether he would like to record an album with him — a proposal that’s met with an immediate nod.

The album that hit the shelves in June 1970 was called My Goal’s Beyond. The guitarist was John McLaughlin. The tabla player was Badal Roy. The rest, to use a cliché — is history.

Roy might have gone to the US with statistics on his mind, but 40 years later, he is one of the most-sought-after jazz tabla players in the world, having performed with the who’s who in music — artistes as diverse as Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Herbie Mann, Dave Liebman, Don Cherry, Pharoah Sanders, Lonnie Liston Smith, Andreas Vollenweider, Steve Turre… even Yoko Ono. He has been an integral part of Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time since 1988 and has collaborated with Brazil’s Duofel, an instrumental guitar duo.

Roy’s story, very like the genre of music he plays, is an eclectic mix of various elements: rags-to-riches, fairytale wonder and — above all — serendipity. With no formal training, he may not be as virtuosic as Zakir Hussain or Trilok Gurtu, the two mostly credited as having taken Indian percussion to the West, but that’s what makes it all the more remarkable. At home in Hooghly’s Konnagar (he still considers this “home”, despite being a permanent resident of New Jersey for over four decades), he recounts how, after recording the album, McLaughlin came down to him one day and told him that a certain Miles Davis — with whom he used to play those days — wanted to check him out.

|

| Badal Roy. Picture by Bhubaneswarananda Halder |

“At that time,” recalls Roy with a chuckle, “I didn’t even know who Miles was. But I decided to meet him anyway”. So, during a break in performance at Taste Of India, he landed up at The Village Gate, “just a couple of blocks away, tablas in hand”, where Miles was performing, and played some beats for the great man. “Miles said: ‘You sounded good!’, and that was that. This was in ’71. Early next year, I get a call from Teo Macero, Miles’ producer, who told me Miles wanted me to play on his album, On The Corner. I couldn’t believe it.”

If the prospect of playing with Miles was nerve-racking, the first day of recording wasn’t for the faint-hearted. Roy landed up with his tablas at the Columbia Studios and took up position amongst the likes of McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock and Jack DeJohnette, among others. “There was no rehearsal, and when Miles strolled in, none of us knew what to do,” he recounts. “All of a sudden, Miles tells me: ‘You start’ — no music, no nothing, just like that. Realising I have to set the groove, I just start playing a TaKaNaTaNaKaTin rhythm. Herbie nods his head to the beat and, with an ‘Yeah!’, starts playing. For a while, it’s just the two of us, and then John and Jack join in. Then all the others start and, to me at least, it’s pure chaos. I’m completely drowned out by the sound. I continue playing, but for the next half hour, I can’t hear a single beat I play.”

When On The Corner released in 1973, it produced a whole range of reactions from critics, mostly unfavourable. To most, Miles’ switchover from modal jazz to dirty street funk — eschewing soloing for the groove — was sacrilegious. It became the worst selling album in his career at Columbia.

Now, of course, it’s a different story. The album, with its “cut-paste” approach, it is thought, prefigured the advent of a whole lot of genres — from nu-jazz, jazz funk, experimental jazz, ambient to even world music.

Roy himself calls the music “several years ahead of its time”, adding he didn’t like it at all when the album had come out. “I didn’t even listen to On the Corner. In the meantime, I played with Pharoah Sanders and started collaborating with Ornette. My son was born in ’77 and went to Rutgers graduate school in ’95. One day, he comes home excited, waving an unopened copy of On The Corner that I had in my basement. ‘Dad’, he says, ‘Students in my college are taking autographs from me because you’re on the album!’ It was then that I finally listened to the CD... and got completely blown away by the sound,” he says. “So many years down the line, with the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to get bowled over by the magnitude of it all and the breadth of Miles’ vision. When I hear hip-hop or nu-jazz, I can identify some of the beats and patterns from On The Corner and I think, Hey! We did that 35 years ago.”

If Miles had provided him the first big break, Roy’s later collaboration with another legend — saxophonist, violinist, trumpeter and composer Ornette Coleman, as part of Prime Time — embodies the jazz-fusion genre at its most mature. And it is here that Roy’s self-taught playing came in most handy. Unfettered by the idiom of classical tabla, he had little problem fitting right in and setting the groove to rhythm structures that were often demanding and frustratingly complex. And Roy is keenly conscious of this. “I am no classical player, nor have ever claimed to be one. I do what I do — and leave the classification to the critics. Coleman, too, found an excellent collaborator in him, and has often described Roy’s music in superlatives.

For someone who’s achieved so much already, Roy is surprisingly unassuming and would rather let his tablas do the talking. Conversing with him, one gets the feeling that the man himself is rather like his music — largely improvisational, always taking baby steps, taking life as it comes, never thinking too far ahead.

Roy narrowly missed out on a Best Contemporary Jazz Album Grammy in 2008 when the critically acclaimed album Miles from India — a “cross-cultural celebration of the music of Miles Davis by India’s foremost musicians collaborating with the legendary musicians who comprised the various Miles Davis bands over the years” — lost out to Herbie Hancock’s River: The Joni Letters. But he isn’t bothered, dismissing it with a shrug.

He’s won over the West all right, but to Indians, Badal Roy still has little recall. To those who equate tabla with classical music, and whose ears are attuned to the sharp tukras of Hindustani classical, his style of playing — a groovy, bassy sound — would sound alien.

But don’t let that fool you. If you have trouble believing the dictum that music is a universal language that transcends barriers, Roy’s story should provide all the proof you ever need.