|

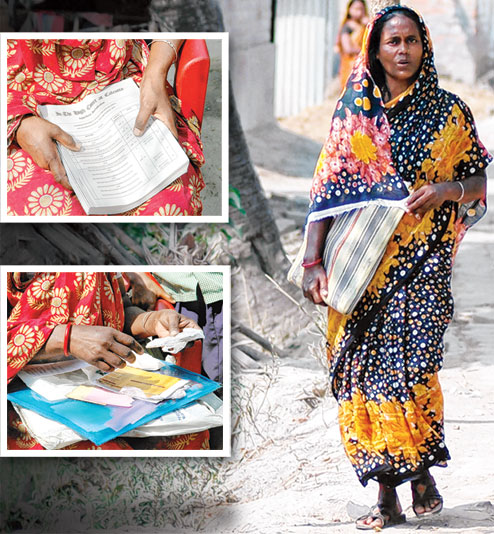

| Sharifa Bibi near her home in Habaspur and (left) the case papers, her daughter’s pictures and other documents she carries in her bag. Pictures by Bishwarup Dutta |

Sharifa Bibi knows the details by heart. She has told her story too many times. On the morning of February 17, 2012, she asked her daughter Amina (name changed), 13 years old then, to go to the brick kiln in their village. Not for a proper work session, but to dry the sand. It had rained the previous night.

Mother and daughter had worked for a week at the kiln and had earned Rs 1,600, and some of it they had happily spent at the Kumorpara fair in the neighbourhood.

Amina had left at 10am and was not yet back at 11am. She was a “good child” and it was not in her to come back late. An alarm went off in Sharifa’s head. She knew something was wrong.

Dumping all her household work — Amina was her first child, followed by two sons and another daughter — she ran into the village. It is more than a year now, but Sharifa is still running from village to neighbouring village in search of her daughter.

She still drops everything and rushes to wherever she sees a glimmer of hope. She will meet anyone, in the villages, in her area, in Calcutta, for that’s the farthest she can come, where recently she has moved the high court.

“I am a madwoman,” says the barely literate Sharifa, a handsome, stout woman who should be in her thirties by her account, though her official age is 47. “I want my daughter back.” It is difficult for her, with her three young children and a husband who earns little, but she will not give up. Her elder son, 12, now works in the fields with his father.

A day after a Haldia fast-track court delivered an exemplary judgment awarding the maximum prison term to traffickers and a compensation to the victims, Amina’s case is a reminder that the course of events in Haldia is exceptional.

But in these restless months of looking for her daughter, Sharifa has accomplished something police could have been proud of, only if they had done a bit of what they were supposed to. With the help of none but a neighbour, she has more or less cracked what she believes to be a trafficking network operating in and around Habaspur, her North 24-Parganas village near the Bangladesh border about 75km from Calcutta. She submitted all the details to the police months back, not to much effect.

On the day Amina disappeared, at three in the afternoon, Sharifa, visiting houses Amina could be in, heard that she had called at the village grocery store, where the phone is used by everyone.

Amina had said that she was at the Taki crossing and being taken away somewhere. She wanted to come home.

That was when Sharifa began her list of phone numbers. She called the number from which Amina had called, and spoke to someone called “Robi”, who claimed that his friend had taken Amina away. Sharifa was asked to call at 9pm at night, but no one took the call.

This was the beginning of a long, elusive trail of names and numbers, usually featuring only the first names of young men who arrived and disappeared suddenly, as ever-changing as their identities and phone digits.

This was also Sharifa’s entry into the slippery, fly-by-night, but immediate, world of “agents” and “agencies” that connect rural Bengal with the big cities.

For three months following Amina’s disappearance, Sharifa would leave for Hasnabad police station, about 5km from Habaspur, at eight in the morning, in a bus, or a “Magic” gari (Tata Magic), and spend the whole day there. She knows the road from her home to the police station by heart too, as she does the faces of the officers.

Her house is at the end of Habaspur, a poor, but neat and pretty village that stretches along the Sonatoli, or Sanatani, which was once a branch of the river Icchamati but now is a long, placid canal after a dam was constructed on the river nearby. The dam meant an end to fish cultivation in these waters as a livelihood for many in the village, some complain.

One day after Amina’s disappearance, Sharifa lodged a general diary (GDE No. 790/12 dated 18.02.2012) with Hasnabad police station, saying that her minor daughter was missing. On March 18, she wrote a complaint letter to the police station that was treated as an FIR and criminal proceedings were initiated in Hasnabad police station in case No. 89/12 against “unknown persons” under sections 363, 366A and 372 of the IPC.

Around that time, through Anwar, an official of Childline, the government helpline for child-related problems, Sharifa met a set of people.

Two persons appeared in the village from Delhi, a woman called Rima and a man called Bapi. Sharifa had made several copies of Amina’s photograph, in several sizes, and Rima said that she had seen the girl. “She told me that Vivek Agent (people operating in villages for placement agencies in cities where girls are taken are established “agents”) knew about my daughter. I tracked him down, in a deserted spot in Lebukhali village in Hingalganj,” says Sharifa.

The journey was strange. “We travelled for three hours to reach a desert-like place,” says Ashraf Ali, Sharifa’s social worker neighbour. With them were Anwar, Rima, Bapi and Bapi’s father Habibur.

According to Sharifa, Vivek told her that he had given up his profession but knew her daughter was with “Bishwajit” and “Akash” and an “agency” in Delhi called Lakshmi Mata Service.

She and Ashraf Ali convinced Vivek to come to Hasnabad police station, but he escaped meeting the investigating officer, though he met the circle inspector. “They came to the police station on July 21,” says Ashraf Ali.

Sharifa had also met up with a young woman from the village, who had disappeared around the time that Amina did. She was trafficked to Delhi but had returned to the village. She was wary, but Sharifa worked her way into her confidence and got the number of a person that looked familiar, though Sharifa did not know the “English” numbers. She matched it with other numbers she had, and this number turned out to be Bapi’s.

Sharifa knew she had made a connection. She was fairly convinced that her daughter was with these men and in Delhi. She claims all of the people, including Anwar, were part of a trafficking network. She wrote it in a complaint to the CID. (Anwar denied the charge, saying he was helping “victims’ families” and the people he knew were “agents” who gave girls respectable work in the cities.)

The police had done nothing so far except arrest a person called Gobinda Biswas on May 5, 2012, from the locality, who turned out to be the driver of a vehicle from whose phone Amina had made a phone call.

He was in police custody for 10 days .

Sharifa had also found out by now that Amina had been whisked off on a motorcycle carrying two men. “She was wearing a pink salwar kurta and had a nose-ring,” says Sharifa.

“I want my girl back. I am ready to give up my house if required,” says Sharifa. “I had her when I was very young. The doctors scolded me. But we kept her alive by working hard. My husband and I worked in Salt Lake in construction sites near the stadium and she stayed with my mother,” says Sharifa.

She had begun to despair, though, after six months. She had met about half a dozen people she suspected of being part of trafficking network and given all the leads to the police. But they groaned on seeing her back again and shooed her and Ashraf away, she says. She stopped her trips to the police station.

Then she decided to move higher authorities. On October 5, she submitted an application to the CID missing persons’ squad at Bhabani Bhavan, listing eight names and phone numbers of persons and Delhi “agencies” she thinks are connected with Amina’s disappearance.

Her case came to light when she met a group of journalists from Calcutta and other places in the state at an event in Basirhat on December 15. Sharifa also attended the public hearing (see below) on cases of violence against women that came out of the Basirhat event in Calcutta on March 2.

Before attending the public hearing, however, Sharifa moved the highest court in the state. On January 13, 2013, she filed a petition (W.P. No. 1864 (W) of 2013) at the high court with the help of Human Rights Law Network, which offers legal aid free to its clients, demanding why her daughter has not been rescued.

At all public platforms, Sharifa speaks quietly but firmly. Only at Hasnabad police station did she show signs of nervousness. At the waiting room of the police station, a slightly grotesque place — where on one wall hang the pictures of two unidentified dead, young women,who were murdered, and on another a tastefully framed NGMA print of S.H. Raza — Sharifa lost her voice as police officers stared at her. Basirhat sub-division is trafficking-prone, says Baitali Gangopadhyay of NGO Jabala. A girl who had run away from a Delhi home was rescued in the area by the police and NGO workers on Saturday.

An officer from the police station had left for Delhi in February with two cases of missing girls, one of them Amina. He went to look for the agency “Lakhmi Mata Service”, mentioned by Sharifa, in the Nehal Vihar police station area in Delhi. Its owner, Rajkumar Sardar, and his wife, turned out to be inhabitants of the Hasnabad locality. His house was raided in the second week of February but he was not found.

The officer-in-charge, Anupam Chakraborty, said the police had taken some time to act because the phone numbers reached them through the Childline official. He said they had tried to contact the numbers but not all were accessible.

The police said that Sardar was now the key to finding Amina, who was likely to be back. It did not seem to have much effect on Sharifa.

She will keep searching for Amina, she says. “Where haven’t I looked?” she asks. “Raghabpur, Bokchhora, Ghonarbone, Jalseria, Shankchuro, Dhoaberia, Naldi, Najat…”

TRAFFICK FIGHT TO-DO

On December 15, 2012, a group of women in Basirhat, survivors of violence or family members of such women, met journalists at an event organised by SAWM (South Asian Women in Media) and Human Rights Law Network (HRLN). The gathering led to a series of public depositions. At a public hearing later, held at the National University of Juridical Sciences (NUJS) in Calcutta on March 2, organised by Jabala Action Research, Self Help Promotional Group, HRLN, NUJS Legal AID Cell and SAWM as a follow-up of the Basirhat event, 21 women from various parts of the state presented their cases. The 14-member jury made the following observations and recommendations. Sharifa Bibi had attended both events.

OBSERVATIONS

Trafficking survivors are mainly school drop-outs

Agents operate at the local level. Traffickers, even those who have been jailed, often continue illegal activities without facing social censure

There is a nexus between traffickers and police. There is also indication of support by political leaders

The police often do not act on complaints. They do not arrest accused, file chargesheets or follow up after filing chargesheets

The accused often get bail within a short time in the absence of evidence

RECOMMENDATIONS

Cases be taken up at the police superintendent or even higher level, and especially by the special women’s cells of state police and CID

The police should be pressured to act by political, social or local community-based organisations

Police should maintain a database of jail-returned traffickers

Panchayats should identify trafficking-prone areas and vulnerable families. They should have a list of traffickers

The cases be heard at fast-track courts

The human rights commission and the state women’s commission focus on these cases and work with community-based organisations and legal-aid institutions

Immediate stopping of the practice of sending girls to work or marrying them off before they are legally eligible

Special counselling for girls be arranged at primary and middle schools. The NUJS legal aid cell has promised help to the individuals and NGOs involved in trafficking cases