|

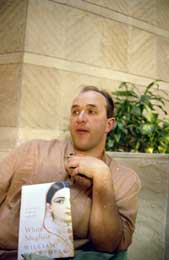

| William Dalrymple talks about his novel and its sequel in Calcutta on Thursday. Picture by Pradip Sanyal |

He might look like a pucca sahib, light eyes, fair skin and all, but in fact, he has a small amount of “Bong blood” in him. William Dalrymple, author of In Xanadu and City of Djinns, found out this “interesting tit-bit”, and many more besides, about his family history while gathering material for his latest book, White Mughals. It’s a factual, yet fascinating, non-fiction novel about a tragic love story of an English ambassador of the East India Company in Hyderabad and a Muslim noblewoman.

“My great-great-great-grandmother was a Bengali. Her husband was a Frenchman stationed in Chandernagore. She converted to Christianity and took the name Marie Monica. There are no records of what her name was before that. So, whether she was a flamboyant Chatterjee or a lowly sweeper I will never know. They both lived and died in India. Their daughter married a Dalrymple,” says the Scotsman, in the city to promote White Mughals.

Another ancestor, who features quite prominently in the book as a “gooseberry between the lovers”, was James Dalrymple. “I was looking through documents and the name ‘Dalrymple’ just popped up. I was quite surprised,” he recalls. “In fact, he later married a Hyderabadi Muslim himself.”

The revelations poured in through five years of rigorously researching the lives of officers of the East India Company, in the pre-Raj period. “To borrow from Salman Rushdie, there was a ‘chutnifying’ of culture from about the 1780s to the 1850s. The British imbibed as much as they gave… I wanted to dispel the myth of the stereotypical, uni-dimensional cardboard cut-out colonial Britisher. I found documents proving they had Indian wives and families, whom they openly acknowledged. At the end of the 1700s and the beginning of the 1800s, one in three British men were leaving their wills in the name of their Indian wives and children. It was like social history being rewritten,” he says.

Dalrymple’s Indian connection began by chance in 1984, when the 18-year-old student-backpacker landed up in Delhi “through a series of accidents”. The love affair with Mughal history and Islamic culture that began all those years ago is still as strong as ever. His next project is a continuation of the Anglo-Indian saga, about how things changed and the lines clearly drawn between the “colonial masters and natives” in Victorian times. It includes a lot of material he hasn’t yet used and can’t ignore. “Things were very different in the 18th Century than the passport-form mentality that became the norm in the Victorian period and still exists today. The need to compartmentalise people by their religion or nationality wasn’t so rigid,” he adds.

Historical books for the average reader is not really available in the Indian market, declares Dalrymple. “They are very academic. That’s perhaps why my book is so popular. There is a huge scope for this in Britain and America, too,” he says. The recent spurt of interest in Islam has added to the popularity of his previous works, he admits. Besides, love stories are always timeless.

“In this case, I found a plethora of material from both continents that I doubt I will ever find again. The sad thing is that the British arm of the family has swank middle-class lawyers in London, and the Indian arm has gone down the social ladder,” he sighs.

For now, Dalrympyle’s basking in the glory of “the best story I have yet discovered”, before he renews work on the ‘sequel’, another take on the enigmatic relationship between the British and the Indians.