The world’s most obese people. Once upon a time, the world’s richest. And for the Mukherjees of New Town Heights, perhaps the most memorable they have met.

That in a nutshell is Nauru for Sandip and Kalpana Mukherjee, retired hoteliers who have worked across the globe. Yet, no experience compares to their time in the tiny Pacific island nation, north of Australia, with its utterly unique culture and customs.

“Our time in Nauru began quite by chance, after I met their President in Delhi,” Sandip recalls. “In 1989, I was manager at Hyderabad House, India’s state banquet venue in Delhi. Nauru’s President, Bernard Dowiyogo, had come for official work and, by the end of his visit, offered me a job. In 1993, Nauru was to host the South Pacific Forum for 16 heads of state and needed someone like me, who knew diplomatic protocol.”

Sandip accepted the post of general manager at the Menen Hotel in Nauru, while Kalpana joined as executive housekeeper. Their young daughters, Nupur and Madhavi, joined them for the adventure too.

Money for free

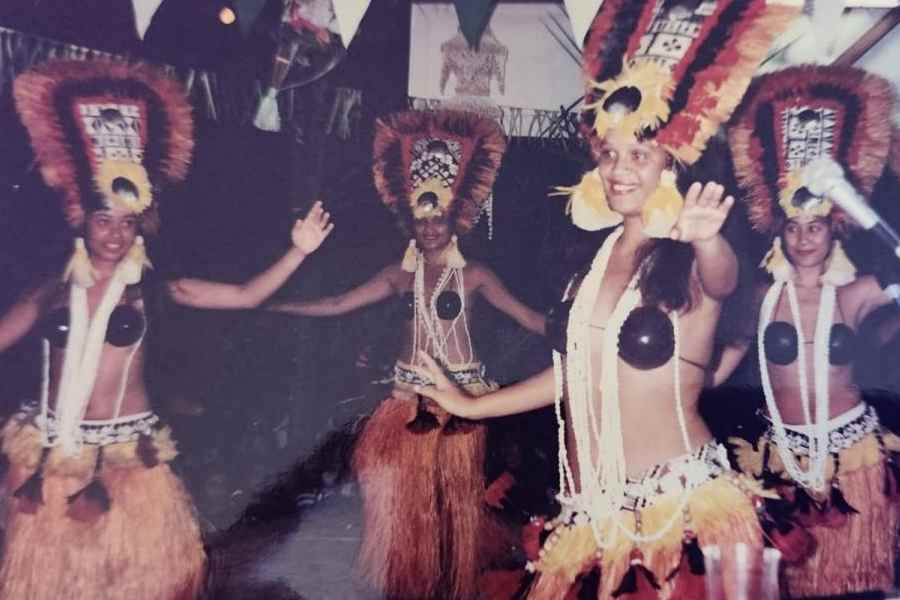

A file photograph of Nauruan dance, clicked by the Mukherjees

Perhaps the first thing that struck the Mukherjees was how arduous the journey was — a three-day trip, hopping from Delhi to Singapore, Manila, Guam, Pohnpei, and finally Nauru. “The island is so small (we could drive around its perimeter in 35 minutes) that there’s barely space for an airport,” Kalpana recalls.

With no dedicated hangar, planes were parked right beside the road, and whenever a flight landed or took off, police cars would block the traffic, like at railway crossings. “But we witnessed the country develop on war footing for the international summit in 1993, which also marked Nauru’s 25th independence day (before that, the country was administered jointly by Australia, New Zealand, and the UK),” Sandip says.

At that time, Nauru was the world’s richest republic per capita. Its soil was laden with the guano bird’s droppings, that had fossilised over millennia to produce the precious mineral phosphate. With a population of under 10,000 and no taxes, it was a tax haven. “Outsiders would arrive in the morning and, by evening, have set up a company, parked their money and left,” Sandip says.

Far from paying taxes, every October, the natives would receive generous royalties from the government for phosphate sales. “Even the hotel janitor would earn thousands of Australian dollars — we’d see them go to the bank, take off their shirts, fill and tie them up with wads of notes, sling them behind their backs and walk out. It was hard to get anyone to work with the incentive of money, since they didn’t need any. But they were patriotic and had a sense of duty,” Sandip says.

Land of milk and honey

Replicas of cannibal cutlery once used on the island

The sudden influx of wealth, however, had its downside. “Nauruans became the world’s most obese people. They ate, drank and smoked almost constantly, and their supermarkets sold the most delicious cheeses, wines, sauces and ice creams. Since they didn’t need to toil anymore, diabetes became rampant,” Kalpana notes.

Sandip’s office was right by the sea, with the waves splashing on its French windows and dolphins dropping by to say hello. “Nauru has gorgeous beaches, but you can’t swim there as the water is full of sharp pinnacles (coral formations) sticking out of the water, and the sea floor abruptly drops 15,000ft. But it does attract deep-sea divers,” Sandip recalls. “Since there were no tourists and only government guests, the hotel perpetually ran at a loss. During my tenure, we earned a profit — a princely sum of $45. The authorities were so pleased, they gifted us a Toyota!”

What’s mine is yours

The island nation of Nauru on the map of Oceania

Culturally, Nauru resembled what one would recognise from images of Hawaii — similar music and dance, and a warm way of life. “There were about ninety-five Indians on the island, and when we celebrated our festivals, the locals would join in. Christianity prevailed, and the nation was divided into nine districts, each with its own church and school. Most teachers were Australian, so the schools taught in English, but for college, everyone went to Melbourne,” Kalpana recalled.

Saturated with phosphate, the land could grow only three types of trees — pandanus (a fruit used to make cheese cake), coconut (which grew three times larger than those in India), and breadfruit (named so for its bread-like smell and texture when cooked). But all these trees had brittle branches, always ready to snap. Fish was the staple, with almost everything else, even food and water, imported on ships that exported phosphate. “It rains any time in Nauru. So to save water, we’d lather up the car and go out for a drive in the rain,” Sandip smiles.

Kalpana tried to start a kitchen garden, but everything would be pilfered. “The culture is one of sharing: if someone likes something on your porch, they’re free to take it. If you invite 10 people, you cook for 20, so the extra can be sent home for their friends and families. Conversely, for Christmas, people would leave expensive gifts at our doorstep, anonymously. To this day, we have no idea who gave us what, year after year,” she says, amazed.

The Mukherjees left Nauru after four years, taking with them some of their fondest memories. “The President himself bid us farewell, and the staff at Menen Hotel presented a signed memento — the only one I’ve ever kept from my career,” Sandip shares, sad at the country’s fate today. “Decades of intensive mining have exhausted the phosphate reserves and plunged the country into an economic crisis. Nauru’s nickname was Pleasant Island, but today Australia uses it as a detention centre.”

The Mukherjees mull visiting the island again, but till that happens, they amuse themselves with a souvenir set they brought back with them — imitation cannibal cutlery. “In the past, Nauruans were cannibals and had special utensils for the meal — a round-topped stick to hit on the head, another to split the skull, and a third to scoop out the treat!” Kalpana laughs.

Write to saltlake@abp.in