|

One of the many fascinating figures in MIT professor Vivek Bald’s book on the history of the first Bengali migrants to the US has jumped out of its pages to guide his African American granddaughter to his roots in Hooghly.

The journey of discovery for the very Bengali-looking Fatima Shaik, 60, began with her ancestry being traced by Bald in his Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America, a revelatory account of how the first Bengali migrants quietly merged into America’s iconic neighbourhoods.

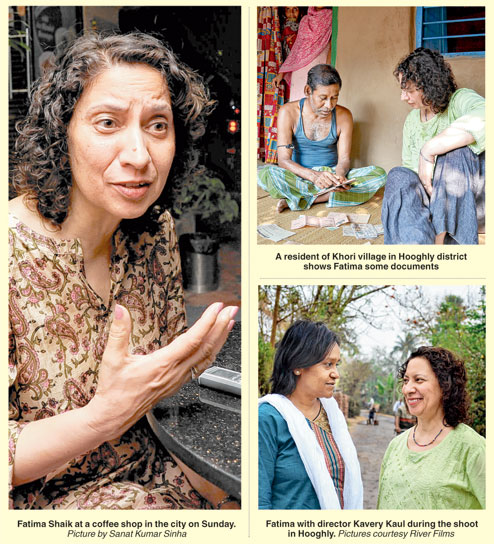

“I consider myself a Black American but I am here on a journey back to my family roots,” Fatima, whose grandfather was a Bengali Muslim from a village in Hooghly, told Metro over masala chai on Sunday.

With Fatima is Calcutta-born and US-bred Bengali film-maker Kavery Kaul, capturing her “African American Bengali Catholic” friend’s cross-continental voyage of discovery on camera for a documentary tentatively titled Streetcar to Calcutta.

The idea of a film had evolved 10 years ago when Fatima met Kavery at the Writers’ Room, a rented space with personal desks in New York. “I found out that she was from Calcutta and we joked that one day we would go to Calcutta together. Then we didn’t see each other for almost 10 years until I ran into her on the street. She was living just around the corner and said to me that now was the time we should seriously do something about it. It was almost like the spirits bringing us together,” Fatima recalled.

After two years of sitting over coffee and scouring through pictures, stories, letters and old records to connect the dots, Kavery earned a Fulbright-Nehru senior research fellowship that would fund her film. She arrived in town in January to do her groundwork while Fatima landed this month.

“It wasn’t just a story about Fatima’s dadu (grandfather) but a story about the Indian diaspora that fits into both sides of my upbringing. This is also about what we have given to America… a story that I want to give back to India, to America and the rest of the world,” Kavery said.

What makes Fatima’s story extraordinary is the lack of any documented history of her community.

“There is no written African American history for specific reasons, all the way through the Civil War…. All the stories were oral or through gospel singing. It was always an underground thing…. Bengali immigrants couldn’t integrate with the White community either; they had the same restrictions as the Blacks because of their appearance. Consequently, stories about Bengalis or Mexicans or French coming into the community were never written,” she said.

It was only a month ago that Fatima, who is from the Creole Seventh Ward in New Orleans, discovered a second African American Bengali within that group.

“In that area, I stand out a little but there are many light-skinned Blacks. They come in every shade, so none of us fit the mould of what one understands by African American. My father had a very definite Bengali look too. The nose mainly. They called it the Shaik nose and he was also tall, skinny and narrow faced. He used to joke about it and say, ‘Oh! I am not from here… I am a Bengali!’ He was always making Indian friends,” Fatima reminisced.

Fatima’s grandfather Shaik Mohammad Musa had left home in Khori, a village in Hooghly, and sailed to the US in 1893.

In 1896, he married Fatima’s grandmother Tinnie, a Black Catholic, and they settled in New Orleans. They had two daughters, Noiman and Haliman. Musa died in 1919, a few months before his son and Fatima’s father, Mohammad Joseph Asad, was born. The children grew up following African American traditions.

“When my grandfather was alive, a lot of Indians from the neighbouring areas would come visiting. But after he died, my grandmother moved to her side of the family. They stayed in that African American community and lost touch with the Indians. Whatever my father learnt about his father was through his sisters’ memories of him,” Fatima said.

In her younger years, the little that Fatima knew about her Bengali origins was through stories circulated within the family.

“My aunt Haliman had done some genealogy studies but when the Internet became popular and you could find genealogical records online, it became a lot easier. I started looking up documents of his arrival at the port of New York in 1894. I found the marriage licence between him and my grandmother and names of other men who came with him. They were a group of Bengali peddlers. Most of them went to New Jersey and New York while my grandfather was the only one that came down to New Orleans.”

One of the highlights of the film-in-the-making on Fatima’s ancestry is the journey to Hooghly, where Shaik Musa came from. It’s a journey that film-maker Kavery describes as “somewhat a detective story”, especially locating Khori, the village where Fatima’s grandfather spent the earlier part of his life. “It’s lovely how Bengalis get excited about all kinds of quests. After asking around and making phone calls, we finally found Khori!” she said of her eureka moment.

The other places from Fatima’s past that she and her friend are revisiting include Collin Street and the remnants of Kalingabazar, where men from Shaik Musa’s village would come to sell embroideries.

“There’s nothing much happening there but we want that. Also Kidderpore, where the ships sailed from. We researched lists of passenger ships and that’s how I found out that he had set sail in 1893,” Kavery said.

More than nostalgia, Fatima’s journey to Hooghly has been “a revelation because I came with no expectations”.

So has she discovered any common traits with Bengalis in Calcutta?

“The hospitality in Khori reminded me of New Orleans, where we sit on the edge of the bed, talk and someone brings out food. That generosity is very much common. And there’s a lot in common in appearance too. Now I am actually starting to wonder if all the African Americans I know in New Orleans might have Bengali roots that they don’t know about!” said New York-based Fatima, who writes fiction and non-fiction and teaches at Saint Peter’s University.

There are also a few stereotypes that she happily fits into. “I am from New Orleans, which is a large port, and eat fish all the time. I love fish! I have also noticed that Bengalis speak loudly and with emphasis. That’s familiar to me because my aunt Haliman and her daughter speak with that same authority, and now I know where it comes from! That’s a Bengali streak.”

What is your message for Fatima? Tell ttmetro@abpmail.com