One has only to flip through the profusely-illustrated pages of the book titled Arpita Singh with text by Deepak Ananth, the Paris-based art historian, to grasp the full and amazing extent of the artist's protean creativity. This well-designed, handy book with good reproductions of Singh's works published by Penguin Studio and Vadhera Art Gallery is the first comprehensive book on the artist, considered a front-ranking practitioner. So much for the soundness of the Indian art establishment's judgement!

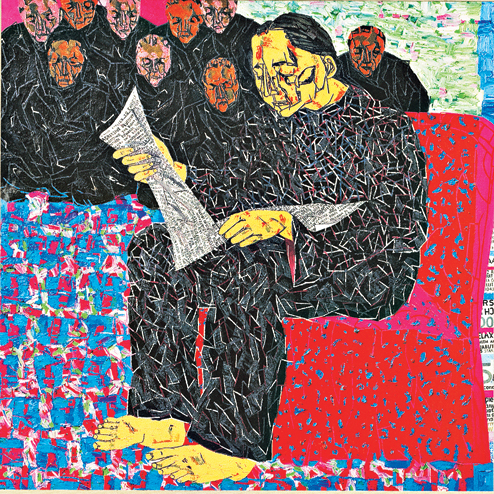

Whatever her medium, be it watercolour or oil paints, Arpita Singh (born 1937) has from the beginning brought together disparate, incongruous, disjointed elements - at times with disturbing effect - within the pictorial space. With the passing of years, this trend became even more complex and idiosyncratic as she evolved a personal language that involved inherited memories and reverie, and broke the bounds of labels such as surrealism that earlier came close to defining her art. For, in the meantime, being an avid reader, Singh had kept her mind open to diverse stimuli - everything from folk art, garden-variety details of everyday life, feminist writing, myths, poetry, textiles (the kantha, in particular), ancient anatomical drawings, cartography, signage... the full panoply of images, words and ideas that earlier books and now the Internet have exposed us to.

This has given Singh's art an elusiveness, unpredictability and ambiguity that is difficult to grasp or pin down. She does this without straining a nerve, easily and effortlessly. One of the pleasures of viewing her paintings is that they are open to diverse interpretations, and who's to stop one if the stippling that characterises much of her work (which Ananth links to running stitches on a kantha) are instead ascribed to the regular marks that fleck the surface of a grinding stone? These are details of domesticity that seem to fascinate her.

So Ananth is justified in connecting the richness and ambiguity of her art to free association, her "childlike vision" and her predilection for "making light" of even the gravest of situations, a quirk he dubs "ludic", which in simple terms means playfulness. Arpita Singh loves to lead you down the garden path till you find yourself in the middle of a conundrum, a gun fight, a street crowded with toy cars, a brace of toy ducks, soldiers emerging from a lily pool, or a sky with aeroplanes winging across it.

In her sketchbook for her daughter are penned a few lines of verse in Bengali (perhaps written by the artist) that speak of an unarmed girl going to a battlefield where she is urged to look for her own weapons, Deepavali, and the magic of the classic, Thakurmar Jhuli. Perhaps they are the open sesame to Arpita Singh's world.

The monograph charts her career which began in the early 1960s, and makes a mention of the Progressive Artists' Group founded in (then) Bombay in 1947, which, Ananth says, represented the "internationalist option". To set the record straight, the Calcutta Group was already in existence in 1943. Ananth writes: "Indian artists were exiled from mainstream modernism, in as much as the conditions that would have enabled them to actively enter into dialogue with it became fully available only after the country had shaken off the yoke of colonial rule." Little wonder Indian artists of that generation found inspiration in modern masters like Chagall and Paul Klee. Another contemporary of Arpita Singh, the late Dharmanarayan Dasgupta, discovered his visual metaphor in Chagall's gravity-defying figures, although for him these were pictorial tropes for poking fun at middle-class mores and venery. At this point one wonders if Arpita Singh's sportive spirit was derived from Mikhail Bulgakov's masterpiece, The Master and Margarita, where the flying lovers summon up associations with Chagall.

Ananth is most thorough in his analysis of Singh's childlike vision with its element of fantasy and her passion for textiles. "Her mannequin-like figures appear like gravity-less objects, as unmoored in the nebulous space as the chairs and tables and fruit and foliage. The topos recalls a generic dreamscape familiar from surrealist painting...." He goes back to the days when Singh graduated from the Delhi College of Art and worked as an artistic consultant for the Weaver's Service Centre, where many major names in contemporary Indian art began their careers. "The textile arts claimed Singh's attention, specifically the traditional kantha embroidery.... Thus, the proliferation of floral or vegetal or avian motifs... all these traits of many different métiers of weaving and quilting and needlework are also distinctive features that come into play in the representational strategies adopted by the painter from the 1980s."

Ananth's power of observation becomes apparent when he expatiates on the impassivity of Singh's figures and the spatial conception of her pictures. "In Singh's case, it is as if the verticality of the figure/ground gestalt of modernist painting is perpetually in tension with the horizontally oriented ornamental all-overness of handcrafted textile practices." Ananth is obviously learned and he quotes copiously from umpteen learned treatises and books. This can get in the way of our appreciation of his writing. One wishes he could make light of jargon, following Arpita Singh's example.

He is also unaware that Arpita Singh is a Bengali who spent her childhood in Baranagar, a Calcutta suburb, and much of her imagery and sensibility was absorbed from what she saw around her.