Calcutta: The village quack has emerged as Bengal's best bet in rural health care with a little training and a new, honourable professional profile.

The state government, struggling to send enough doctors to the villages, has started a certificate course for quacks in basic medicine, ethics of medical practice and legalities so that they can take health care to the grassroots.

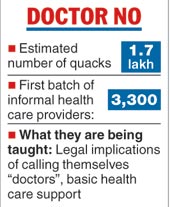

According to an official estimate, 1.7 lakh quacks are active across the state. The first batch of 3,300 candidates from among them will complete their six-month training later this month and become "informal health care providers".

The training module for this new health care army is based on a pilot project started in 2013.

"People selected for the programme are trained to identify when to send a patient to a doctor and what to do when someone requires immediate lifesaving intervention. They are also informed about the legal implications of unauthorised persons prescribing drugs," said an official of the health department.

The minimum qualification required of a candidate for training as an informal health care provider is higher secondary or equivalent.

Bengal currently has a shortage of around 2,000 doctors, mostly in rural health care. The training programme for quacks willing to make the transition to informal health care providers is meant to partially fill the gap. "They are the ones to whom most people in rural Bengal turn to first whenever they fall sick," the health official said.

Villagers with medical conditions that can be treated at primary health centres are often forced to visit state-run teaching hospitals in Calcutta because there is no professional they can rely on closer home. These hospitals are overcrowded at all times despite the government discouraging referrals.

The informal health care programme that seeks to correct the imbalance is similar to that in the US and the UK, where a trained medical service provider is called a "physician assistant" or a "physician associate".

The informal health care providersbeing trained in Bengal are expected to coordinate with professionals and provide basic health care to a patient before a doctor steps in. Almost 90 per cent of the population in villages does not have access to health care institutes within 30 minutes of travel. Most block primary health centres do not have adequate staff.

"Our informal health care workers are already there, whether we accept or deny it. People in rural areas consult them and so it is better to provide them training," said Chandrima Bhattacharya, the minister of state for health.

The second batch will be trained from January. "We expect training to make them more responsible," said Abhijit Chowdhury of the School of Liver and Digestive Diseases at SSKM.

Chowdhury is also the secretary of the Liver Foundation, West Bengal, which had conducted the pilot project.