|

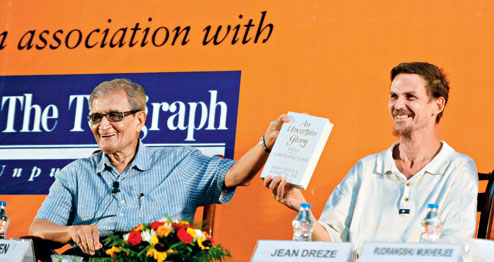

| Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze launch An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions, organised by Penguin Books India in association with The Telegraph, at Nandan on Monday evening. Picture by Amit Datta |

Nobel laureate Amartya Sen busted a few myths about himself in front of a near full house at Nandan-I on Monday, interspersing discourse with doses of humour to debunk in the process myths about India and its celebrated story of growth.

Myth No. 1: Sen does all the hard work while co-authoring books with development economist Jean Dreze.

“I am delighted that Jean has done 90 per cent of the work. His memory is faltering because when I first told him that he did 90 per cent of the work and I got 90 per cent of the credit. He protested and said I thought it used to be 95 per cent [laughs], so it’s been downgraded a little from that,” the 79-year-old said.

Dreze had said moments earlier that “Amartyada tends to do most of the work and I get most of the blame!”

Myth No. 2: Sen’s ready stock of B.R. Ambedkar quotes means he likes slogans.

“I am very suspicious of slogans, always.”

Myth No. 3: Sen is a great believer in the “trickle-down” effect of economic growth.

“I have never used that term. I don’t think it sounds good either.”

Myth No. 4: Sen (and Dreze) advocate a return to the culture of subsidies.

“We are basically against subsidies, but for some reason the book has got identified with food subsidy, partly because of Jean’s activism on that subject…. I saw in a newspaper that I was being described as the ‘father of food subsidies’. That seems to me to be the closest thing to a paternity suit that I have ever faced!”

For the most part, the launch of An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions, organised by Penguin Books India in association with The Telegraph, alternated between a friendly push and a gentle prod for the audience to realise how growth can be a chimera for a country still far from the cusp of change in terms of public welfare.

Sen and Dreze’s arguments were restrained rather than impassioned, the thought behind the sentence seldom overshadowed by the force of the words spoken. In a way, it mirrored the long, arduous road that two of India’s foremost economists have taken to bring development economics out of the ambit of scholastic pursuit and policy making.

If Dreze described his third collaborative book with Sen as a “wake-up call” for those who had failed to see beyond India’s economic growth over the past decade and more, the Nobel laureate said it was wrong to assume that the book was a challenge to the tangible impact of the economic path that the country had taken.

At its core, Sen said, Uncertain Glory was an effort to engage and tell India how and why it has ended up behind an economically far weaker country like Bangladesh in key human indicators.

“We believe that India is in a very difficult situation now and the glitter of the achievement might well hide that. We do want many, many changes that include reforms, which has made a contribution to India and could make more but it requires not just policy changes, it also requires quite a fundamental change in politics and the political economy of the country.”

Sen iterated that there was “no quarrel” with the pro-reform agenda but “there is some quarrel with being contented just with pro-reform and not seeking those very basic changes that the country needs”.

|

Ambedkar, whose philosophy Sen and Dreze refer to several times in the book, again came into the picture when the Nobel laureate spoke about what Uncertain Glory seeks to achieve. “The moving spirit of the book is captured well by a phrase that we use, I think, repeatedly in the book from Ambedkar: educate, organise and agitate.”

Sen said “to educate” was crucial because “being misinformed about what’s ailing Indian society and the economy had a huge responsibility in our not doing the things that we should be doing”.

“Education is very important to see and that’s why we don’t apologise for the 50-60 pages of tales; we ought to know what the country is like, that includes some success stories but it also includes a lot of non-successes and failures. It includes the society as well as the economy, the public as well as the government and the governing party as well as opposition in Parliament and all the other institutions that go with it, the media, NGOs and so on.”

When a face in the audience who identified himself as a medical practitioner suggested that Sen should take the initiative in introducing “medical economics” for MBBS students as health care was such an important component of public welfare, Sen brought the house down with his response.

“I am sceptical of people in medical schools doing economics and even more sceptical of my doing it! Medical schools do need to have more discussions about why they are doing what they are doing, what they can do and so forth and a lot of these issues relate to economics, so that I agree with.”

To a question on how far the WHO slogan “Health for all by 2000 AD” had been achieved, Sen responded with a story. “I don’t know about the WHO slogan. I am very suspicious of slogans, always. When I first arrived in Cambridge, one of my teachers told me, ‘Look, you have to be very careful, you have now come to a village’ — we always used to call Cambridge a village — where no economic theorist rests until a theory has been converted into a slogan. And the WHO slogan isn’t a very good slogan either!”

At the Q&A session, moderator Rudrangshu Mukherjee from The Telegraph asked Dreze whether the book’s opening quote from Shakespeare’s The Two Gentlemen of Verona — “O, how this spring of love resembleth/The uncertain glory of an April day” — meant that the “looming shadow of inequality and poverty” would blight India’s progress to the extent that it becomes two different nations, one resembling sub-Saharan Africa and the other California.

Dreze, as understated as he is unassuming, said: “No, I don’t think it’s an all or nothing scenario. I think it’s a mixed picture. And the main point is that all depends on what we do.”

Sen had earlier summed up his enduring partnership with Dreze by pointing to “believing in the same thing” as being the bedrock of their collaboration.

He said the fundamental idea they were trying to explain was essentially a simple one — that economic growth is very important but pointless without addressing the human condition.

“Let me comment on a few things that we do want to say and that we, in particular, do not want to say. It is sort of dialectical, what I want to say and what is it that we are denying and, in the context, what is it that we are asserting,” Sen explained.

“It (the book) is really a joint work and we have worked together and in different parts with greater emphasis in some cases on Jean and other cases on me, and I am delighted that we are able to arrive at a position with which both of us are in agreement. It is quite important to agree with your own book [laughs]; it could be very difficult to defend it otherwise,” he said.

Defend the duo did. And how!