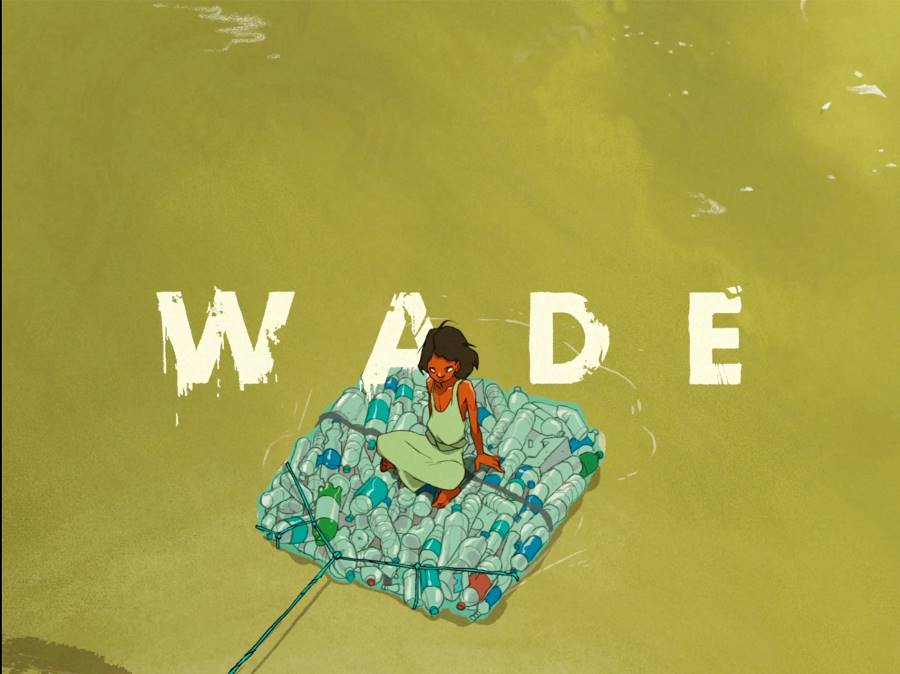

A blind girl sits on a raft made of discarded plastic bottles floating in depressing green waters. One end of the raft has a rope affixed. A woman who might be the girl’s mother — there is no way of knowing for sure as there is no dialogue or text on screen — pulls along the rope even as she braves the waters to move through a cityscape. The viewer will recognise the outline of Howrah Bridge, of Victoria Memorial, the stretch that is Park Street.

The familiar markers in an unfamiliar and the most extraordinary state achieve the same effect as apocalypse films. According to Kalp Sanghvi, 26, who has made Wade with Upamanyu Bhattacharyya, 28, the 10-minute animation film belongs to the genre “climate change horror” or “ecological horror”.

The storyline is simple: pushed by climate change, the rising sea has taken the city hostage. Human beings have been driven out of their habitat and so have the tigers. And when they come face to face, a tussle for survival breaks out.

A scene from the film Wade Courtesy, Kalp Sanghvi and Upamanyu Bhattacharyya

A quiet urgency imbues the animated characters. The man who leads the humans has a mask covering the back of his head; it is meant to trick the tigers into thinking they are being watched. The soundtrack enforces the doomsday effect. Bhattacharyya reasons, “We wanted it to be like a horror film where climate change is the ghost or villain.”

According to Wade’s creators, the trigger for the film was a 2015 newspaper report on the sinking and shrinking Ghoramara islands of the Sunderbans and climate-change refugees. Says Bhattacharyya, “It shocked us to know that the islands were beginning to go under water because of climate change and not because of tidal activities. People were being displaced and rendered homeless. People being forced to move as a direct result of climate change is worrisome.” Sanghvi adds, “We thought it is already happening, Calcutta is next.”

The film is at once a creative exercise and a red flag. The attention to flesh out the locale is deliberate; it is meant to enforce the urgency of the situation. “Park Street is such a happening part of the city. Imagine it being under water... The pink board of Flurys is a reminder of all the happy times,” says Sanghvi.

Frames change. A pack of tigers appears out of the water taking the humans by surprise. The humans counter with knives and sharp-edged sticks. The leader of the man-pack is killed. An infant bawls and for fear that the noise will draw the attention of the tigers, it is drowned. The baby struggles a bit and then goes still. A tigress delivers a cub. A tiger is killed and the humans cut its limbs and eat the flesh.

A scene from the film Wade Courtesy, Kalp Sanghvi and Upamanyu Bhattacharyya

To work out the consequences of the imagined state of the city, the duo read books, surveyed the city on foot, photographed it extensively. The film was ready by November 2019 after a crowdfunding campaign wherein Bhattacharyya and Sanghvi achieved their target of Rs 4.5 lakh in under three days. For the next three months, they travelled with Wade all over the country for screenings at private venues for a select audience. In May 2020, it premiered at Germany’s Stuttgart Trickfilm International Animated Film Festival.

Audiences, however, seem to have taken note of Wade only post the supercyclone Amphan that ravaged Bengal in May. It seems many sent in photographs of the post-Amphan scene and pointed out the similarities with the film.

The visuals from Wade show how the bustling metropolis has been reduced to a silent swamp. Garbage all around. Crocodiles lurking on the main thoroughfares. Frogs in front of the Metro station. Crows cawing ominously, buildings overgrown with shrubbery, waterlogged streets, abandoned railway stations and deserted tram depots.

Says Sanghvi, “People think they have enough time to figure out (climate change) just because it is not visibly affecting us. One does not realise that time is passing, climate change is creeping into our lives and soon we will have to face the consequences.”

Would they reimagine the film if given a chance, post Covid-19 and the cyclone? The duo says, “We wouldn’t, because people haven’t changed much even after it.” In the film, a snake slithers past an electricity box plastered with torn posters that read, “Climate change is a lie, AC install.”

Bhattacharyya calls both the virus and the supercyclone “tips of the iceberg”. He says, “It is inevitable. You may disagree about sea level and by how much it is expected to rise, but what cannot be contested is that people are going to lose their homes, their livelihoods and be forced to move.”

He adds, “We know an animated short film cannot alter the way people think about climate change, but it is time to wake up.”

A scene from the film Wade Courtesy, Kalp Sanghvi and Upamanyu Bhattacharyya

The Heat Is On

- The Indian government prepared the first ever national report on climate crisis this June

- India’s average temperature has increased by 0.7° Celsius between 1901 and 2018

- The temperature is expected to rise by 2.7°C by 2099. In a worst-case scenario, there will be a rise of 4.4°C

- The projections mean that there will be longer dry spells alternating with very heavy rain

- An increase by 2.7°C is enough to contribute to food insecurity, higher food prices, income losses, adverse health impacts and population displacements

- Climate change can also cause India’s GDP to decline by up to 9 per cent