Prosit Roy's film, Pari, was scary no doubt. Moreover, the fact that it was shot in Calcutta and the South 24 Parganas, made it all the more difficult to shake off that eerie feeling in a hurry. You couldn't help look over your shoulder for a week at the very least.

And yet, Bengal and Bengali literature have typically been known for a most endearing menagerie of spooks. Ghost stories out of Bengal have been funny and imaginative and nuanced, and also a crafty commentary on that which was the past - the Sanskrit word for which is also bhoot. Far removed from horror, the ghosts of Bengal, genial and convivial, highlight the horrors and pathos of the human condition. Here's an off-the-cuff tally:

Subalterns

In Leela Majumdar's works we come across the subaltern bhoot - the mahout, the fisherman, the tribal. Her short story, Tepantorer Paarer Bari, is about the ghosts of refugee children. It goes thus. A house-owner has been trying to sell his ancestral home for years but without success. It is rumoured to house ghosts. At long last an organisation approaches them. It wants to buy the house and turn it into a shelter-cum-school, but there's a condition. Someone has to spend a night at the house and scribble the lord's name all over its walls. The desperate house-owner enlists the help of two little boys, named Notey and Guru, with the promise of 15 rupees and an elaborate midnight meal.

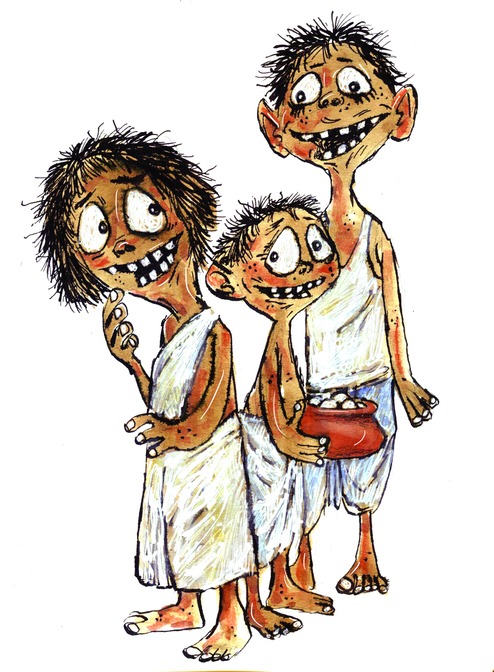

When the two boys approach the deserted house, they find it swarming with a bunch of rowdy children - thin, emaciated, ill-clad, seemingly unwashed, hair tousled. The ragamuffins want to know what is inside the tiffin carrier. Upon seeing the contents - kachuri, alu chaat, achar and jibhe goja - they fall upon them, as if hungry for several centuries.

As it turns out, they might be lacking in manners but not in heart. To express their gratitude for the food, they help the boys scribble " Hori naam" and win their bet. And before the two bravehearts take their leave, they extract a promise - nothing but the shelter must come up here, or else...

Ahididir Bondhura is another short piece by Majumdar. Here, the protagonist is a childless woman who cooks and feeds a bunch of perpetually hungry children. None of them can talk, a fact that perplexes Ahididi. Months later, when she shifts residence, someone tells her that the house she used to live in was haunted - by ghosts of children who had had their tongues chopped off by a cruel merchant.

Do-gooders

The subalterns have their own set of problems but they are principally do-gooders. Take for instance, this one from Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay's novella, Hetamgarher Guptadhan. Madhab Chaudhuri is a displaced descendant of the zamindars of Hetamgarh. One day he comes to meet Nandakishore Munshi, a neighbourly spirit perched atop a tree. By way of reflex he is about to chant Ram naam, except that numbed by fear he has forgotten Ram's name. He mutters, "Er that fellow. The elder son of Dashrath. The one who snapped the Haradhanu like a twig. The same who married Sita. Arre, that one who fought Ravan."

Munshi patiently hears him out and then offers gently, "You must be looking for the word 'Ram'."

Mukhopadhyay tells The Telegraph, "I don't want to scare my readers. Besides, I personally believe in ghosts as possessed of the milk of spooky kindness, and the writings are the personification of this belief."

Most often than not, these friendly ghosts come to the rescue of children. Lonely children, ailing children, convalescing children, children who have been rebuked by their parents, children who are not exactly shining in school.

You realise that even then, mathematics was a bigger ana-thema for schoolgoers than any ghost variant. In Gosai Baganer Bhoot, Mukhopadhyay's protagonist is Burun, who, shamed by one and all for getting 13 out of 100 in mathematics, wanders into a den of ghosts. There, a ghost, Nidhiram, takes the sulky boy under his wing and works on his flag-ging spirits.

Years ago, in Aahiritolar Bari, Majumdar also wrote about a boy who ran away from home - after failing in mathematics in the final exams - to the abandoned mansion of his forefathers, where the ghost of a progenitor lent him an ear and also the family mathematics tutor, Kutti.

HaveLots

The owner of the mansion in Aahiritola, Shibubabu, is a departed aristocrat, possibly from the 19th century. He wears a flowing robe, headgear, nagras with curly tips on his feet and a huge gemstone on his right ring finger. At the drop of a hat he barks orders to his menials. "Pardesi! Ameen!" he hollers. They serve the boy snow-white luchis, sandesh, chhana makha on a silver platter and a glass full of badaam sherbet.

If Aahiritola mirrors the class hierarchy, in his play Bancharamer Bagan, Manoj Mitra underlines the class struggle. There is a poor gardener, Bancharam, and an avaricious zamindar, Chhakari. When alive, he wanted to cheat Bancharam of his plot of land, and even in death he remains single-mindedly greedy. His son Nakari continues to abet Banchha to commit suicide so he can acquire the land.

Mitra's play is more satire than ghost story, but more effective for thus invoking the nether world to emphasise the enduring land lust of the HaveLots.

Satyajit Ray introduces us to a different type of aristocrat bhoot in his Tarinikhuro series. Tarinikhuro, a wanderer turned storyteller, meets the spirit of king Shatrughna Singh who had put a trigger to his head, apparently driven mad by an exotic emerald that he had acquired. Then there is the ghost of another royal, Adityanarayan, who had been killed in a palace intrigue by his own brother. By Ray's own admission, the ghosts in this series are a conflicted but deeply dignified lot.

Ladies

But perhaps more universally resonating than any class conflict is the power struggle between husbands and wives. Not surprisingly, a lot of these stories written by men in an era when divorce was not an option, echo a wish to be rid of the wife. Sometimes, as in Troilokyanath Mukhopadhyay's Lullu, it is said half in jest. One evening, the human Amir happens to say " Leh, Lullu," when a passing ghost by the name of Lullu assumes someone is offering him something of his choice. Full of mischief, he makes away with Amir's wife.

In Bhushundir Maathe, Rajshekhar Basu makes his point about marital arts in rip-roaring fashion. The story begins with a tormented husband, the upper caste Shibu Bhattacharyya. He and his wife, Nrityakaali, have this perennial bicker going. One day, things get out of hand and Nrityakaali brings the broom down on Shibu. A deeply humiliated Shibu prays to Ma Kaali to send a bout of cholera his wife's way. The gods mix up the request; after a hearty meal of roast fowl, curry and eight Devil chops, Shibu dies of acute dysentery.

Basu, who wrote in the Forties and Fifties, indulges in some wish-fulfilment of his own. The Sahib bhoots, he writes, have limited freedom after death and are largely confined to a waiting room that they cannot leave without a pass.

And Shibu's story unravels thus. In time he discovers a camaraderie with two other ghosts. Kariya Piret, who speaks in Hindustani and seems like a servile bhoot, and Nadu Mullick, the retired daroga. Both Kariya and Nadu were much-persecuted husbands when alive and both had been set free of this bondage naturally, when their wives fell prey to chicken pox and the 1947 famine, respectively. But kinship cannot plug the vacuum in Shibu's heart.

For a while he cannot decide between the three pretty women in his immediate vicinity - a petni, a shakchunni and a dakini. After much introspection, he decides to marry the dakini. And then comes the shock. On the appointed day, the new bride unveiled turns out to be Nrityakaali. Interrupting the reunion, the rebuffed shakchunni and dakini also burst on the scene. They are Shibu's wives from his earlier births. And the next thing you know, Kariya Piret and Nadu Mullick - Nrityakaali's husbands from her previous births - are also raising hell.

You might want to keep that in mind.