tired climbers from the 1960 expedition

There is something called the near point of the human eye. If anything is kept at a distance nearer, the eye finds it difficult to focus. And that is why we must begin our story from the far point - that farthest point at which the image still retains clarity, doesn't blur to the eye. That is why we begin our story with Poland.

World War II saw the tiny nation in central Europe pillaged in turns by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Then came the Cold War followed by the Communist regime. Sliced, diced and violated in every possible way, the crushed country gave birth to a strange tribe, a brood of climbers with an indomitable spirit who surmounted peak after Himalayan peak, inadequate alpine equipment and insufficient funds notwithstanding.

Indeed, Jerzy Kukuczka, Krzysztof Wielicki, Piotr Pustelnik, Wanda Rutkiewicz and others made the world sit up in the 1970s and 1980s.

But fact is, almost a century before them, surmounting a different set of odds altogether, the first civilian mountaineering expeditions had rolled out of here, India, and the state of Bengal.

Piyali Basak is thrilled. The 35-year-old primary schoolteacher from Chandernagore, the erstwhile French settlement 50 kilometres from Calcutta, has just returned from a solo hike to a village in Nepal.

Thame, which is close to the base camp of Mt Everest, is home to many famous sherpas - the name for the ethnic group in Nepal skilled at mountain climbing. Piyali was told it is the birthplace of Tenzing Norgay, the first man to summit Mt Everest with Edmund Hillary. She says, "It was a pilgrimage as well as an altitude acclimatisation exercise before I set off for an expedition to a high peak."

Piyali is no novice to Himalayan terrains. Between 2008 and now, she has scaled four 6,000m peaks and Mt Kamet, in the Garhwal region, which stands even taller at 7,756m. She has taken advanced courses in climbing at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling and the Indian Mountaineering Foundation (IMF) in New Delhi. Come September, she plans to summit - the term used by mountaineers to connote climb or ascent - Mt Manaslu (8,163m) in Nepal.

Women like Piyali are a minority in this male-dominated adventure sport. That apart, Piyali is a lone ranger of sorts. This means organising funds on her own, training on her own, arranging her mountaineering gear, food and everything else one might need during an expedition. But this is not the norm. Most mountaineers are members of clubs, some of which, in turn, are affiliated to the IMF, the apex national body for organising and supporting mountaineering and rock climbing expeditions. Bengal today has 150 clubs, many of them affiliated to the IMF. Shyamal Sarkar, secretary of one such club, Parbat Abhiyatri Sangha, says, "Not all clubs function properly. Often disgruntled members of a club split to form a new club."

The Mountaineers' Association of Krishnanagar was founded in 1986 in Nadia district. Basanta Singha Roy and Debasish Biswas are members here. In 2010, they made the first successful civilian expedition to Mt Everest from the state. This was followed by successful climbs to Kanchenjungha and Annapurna.

These summits gave a tremendous boost to climbers in the state. "Many young men and women have come forward to become mountaineers after this," says Debasish, who encourages and guides youngsters like Piyali. His accounts of expeditions have been turned into Bengali bestsellers - Everest Shirshe Bangali, Kanchenjungha: Swarnashikhare Bangali, Aparupa Annapurna. "It fills my heart with joy when I go through the annual list of expeditions carried out in India and find that 65 per cent of them are from Bengal," he says. The list is put together by the IMF.

Malay Mukherjee is one of Debasish's protégés. The 37-year-old member of the Howrah District Mountaineers and Trekkers Association has scaled many difficult peaks - Mt Kamet, Mt Nun, Nanda Ghunti and Mt Everest.

Says Malay, who is a part-time yoga instructor and trekking guide, "My dream is to scale the Seven Summits [highest peaks in each of the seven continents] and be the only Indian to scale the most number of 7,000m peaks." He has scaled four thus far, out of a list of 40 in India alone.

The Polish mountaineers would sing, " W góry, w góry mily bracie/Tam swoboda czeka na cie." Meaning, "To the mountains! To the mountains, dear brother! - There freedom awaits you."

Those who showed the way to the Piyalis, Debasishes and Malays, lived and laboured at least a hundred years ago. Babu Sarat Chandra Das was one such, a headmaster at a Darjeeling boarding school. He went on an expedition to Tibet in 1879. We are told he discovered a new route through the northern valley of the Kanchenjungha. There were others, such as journalist Jaladhar Sen and writer Umaprasad Mukhopadhyay. We know of their treks from their carefully noted travelogues, diaries and autobiographies.

Piyali had said that pilgrimages undertaken with her parents to Kedarnath, Gomukh and Amarnath had kindled within her an abiding love for heights. Turns out, these pilgrimages used to be the base and summit of the mountaineering spirit of many a man and woman from Bengal even half a century ago.

Contrary to popular belief, the first training institute for mountaineers in South Asia came up, not in Nepal, but in Bengal. In 1954, chief minister B.C. Roy, with the support of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, set up the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling.

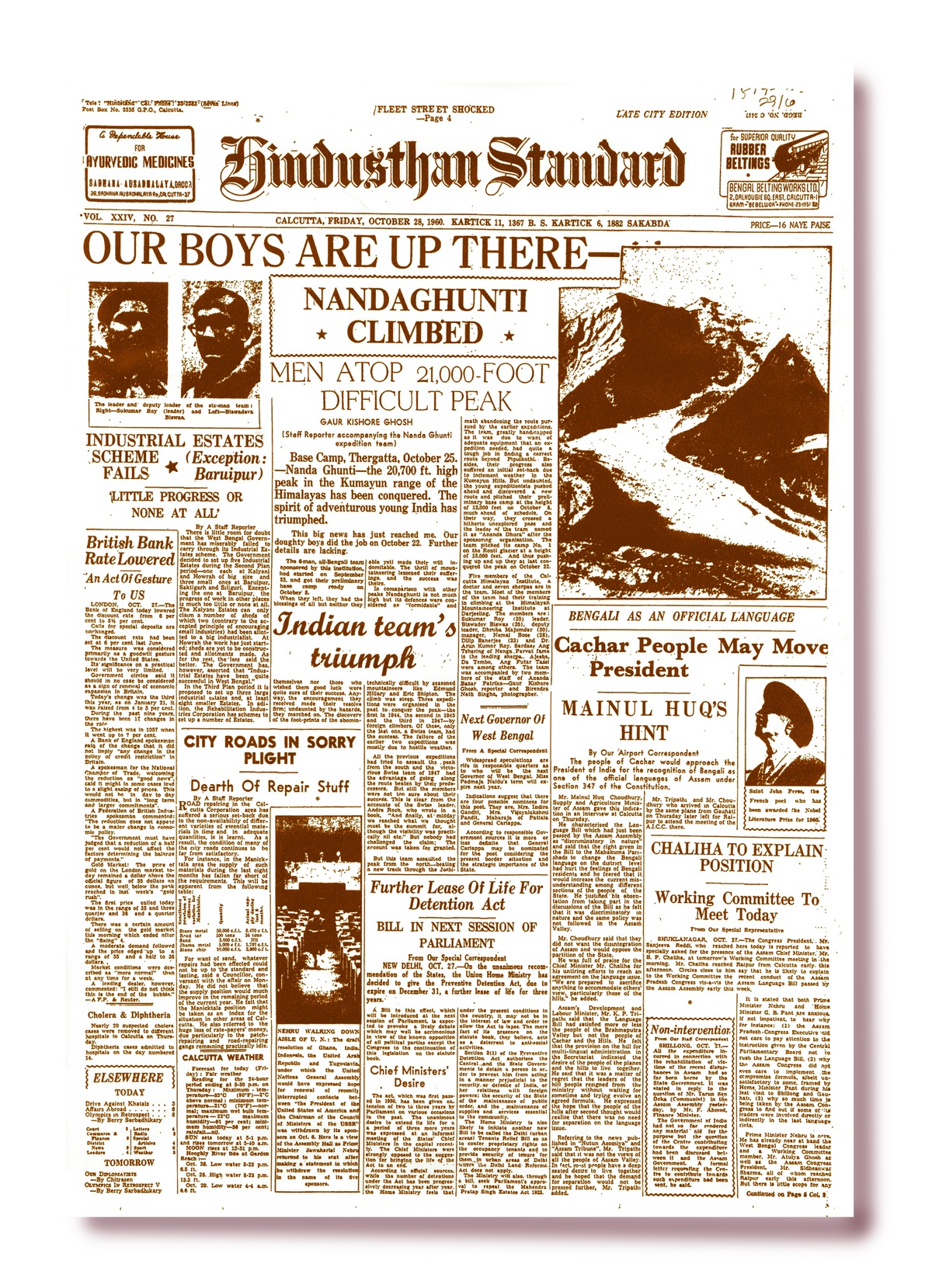

But the dream soared to new heights when a group of mountaineers from Calcutta scaled Nanda Ghunti, a 6,309m peak in Garhwal, in 1960. Led by an employee of the Calcutta Corporation, Sukumar Roy, and sponsored by the Anandabazar Patrika group [which owns this newspaper], these six mountaineers discovered a new route to the summit.

The team was accompanied by a rep-orter and a photographer, Gourkishore Ghose and Birendra Nath Singha. On Oc-tober 28, 1960, the front page of Hindusthan Standard [owned by the Anandabazar group] read: Our boys are up there. Nanda Ghunti climbed.

The Himalayan Association, the club that organised the expedition, soon spawned a number of mountaineering clubs across West Bengal.

Like a lot of their Polish counterparts, most mountaineers of Bengal were and continue to hail from lower middle-class families. They have Himalayan respon-sibilities and meagre sources of livelihood. But it is the desire to conquer distant peaks that propels them through the mundane, bring out super-human qualities, and catalyses a Clark Kent-to-Superman kind of transformation.

On her schoolteacher's salary, Piyali runs a family of four. Her father, a retired businessman, suffered a cerebral stroke some years ago and is now afflicted with Alzheimer's disease. Every evening after returning from school, Piyali spends three hours practising taekwondo. Other than that, all her spare time is spent trying to garner funds. She needs Rs 7 lakh for the upcoming expedition to Manaslu. She tells us, "I expect to get about Rs 2 lakh from the youth affairs department of the West Bengal government, but that won't be enough."

Photographs by Josh Haner, The New York Times

Go tell it to the mountains

A perennial lack of funds often forces mountaineers to cut costs and corners. Piyali remembers how her team had to cancel an expedition to Mt Kamet because they could not arrange for food and expedition gear.

Malay is also busy hunting for sponsors for his expeditions. He tells The Telegraph that an expedition to Mt Everest can cost around Rs 24 lakhs - a royalty fee of Rs 7.5 lakh has to be paid to the Nepal government, fees to the tune of Rs 5 lakh for the expedition agency that will provide porters and other services, sherpas have to be paid Rs 3 lakh each and so on.

Sometimes climbers take hefty loans, mortgage property and family jewellery to fund expeditions. For his first summit in 2014, Debraj Dutta - he holds a part-time job as a trekking guide - had arranged for Rs 18 lakh, but the expedition was called off after an earthquake. When the expedition finally happened two years later, Debraj had to pay Rs 32 lakh in all; costs had gone up. He had found himself sponsors, but even after that he had to take a loan of Rs 4 lakh. He says the first thing he did after reaching the summit was plant flags of all those organisations that had funded his expedition. "You are under tremendous pressure to succeed because so much money is involved, even though sponsors never force you to risk your life for a summit," he says.

In the summer of 2016, 11 people from Bengal set off for Mt Everest. Two others attempted the neighbourhood peaks of Lhotse and Dhaulagiri. While most were successful, four of them - Subhas Paul, Paresh Chandra Nath, Gautam Ghosh and Rajiv Bhattacharya - died.

Later, it emerged that those who succumbed to death had gone for the expedition with little preparation for the brutal circumstances at such high altitude. Rather than focus on rigorous physical fitness and proper planning, they were forced to focus their energy on scraping funds until two days before the expedition kicked off.

Recalls Malay, who successfully made the summit on the same day, "I found them climbing up while I was descending. They started quite late; the delay must have turned fatal." Debasish chips in, "They should have quit when they were fatigued and got delayed during the ascent."

While the body of Subhas, a truck driver from Bankura, was retrieved, the corpses of Gautam and Paresh remained lost in the snow for more than a year. It took eight sherpas and an arduous expedition sponsored by the Government of West Bengal to retrieve those bodies, which were then flown to Kathmandu. It is ironical that while there is no one, or easy, way of accessing funds for expeditions, the state readily spent Rs 2.5 crore for repatriation of the dead.

Sabita is Paresh Chandra Nath's wife. She lives in Durgapur with their 10-year-old son. Two years on, she is somewhat coming to terms with the death of her husband. The West Bengal government helped her get a temporary job in the local municipality. When we call her, she has just returned home after ferrying her son from one tuition to another. She is happy to reminisce at length about her husband, whom she very obviously valorises.

She talks about how he dared to climb Mt Everest at 58 and died of the effort, how he had lost his left hand to an accident in his childhood. "He sewed backpacks and tents for trekkers and mountaineers to feed his dream and earn a livelihood. He was so good at it that he could make a huge tent for 15-20 people." With one hand? She says with pride, "He could navigate the ropes, fix carabiners and handle the ice axe with equal proficiency. He had trained so many young climbers."

Piyali says she had ascended Mt Tinchenkang notwithstanding a large tumour. It had to be operated later. "Ever since, I don't feel scared of the worst avalanche, landslide, blizzard," she says.

Debasish nearly died of a cerebral stroke during his last expedition to Dhaulagiri. He had forgotten to carry with him a vital medicine. He says, "You can die of hypothermia. You may lose a body part to frostbite. Death lurks in the crevasses."

We learn from Malay that mountaineers are used to walking past corpses during the climb. He says, "One time I had to share tent with the corpse of a dead mountaineer. What could I do?" He is not scared of death. He has just got engaged to another mountaineer from Alipurduar. He adds, "She knows about the risks."

In the foreword to the posthumously published autobiography of the Polish mountaineering legend, Jerzy Kukuczka, titled Challenge the Vertical, his wife, Cecylia, writes: Mountains were his life and the mountains claimed his life. There he remained. Could it have been otherwise?

Sabita Nath also says, " Uni pahad bhalobashten. Tai pahadei pran diyechhen. Pahad-i chhilo onar bhagaban... He loved the mountains. And therefore, it was fitting that he died among them. He venerated the mountains."

Near point is too close to the eye - so close that it sometimes blurs to the attention, if not to the eye.