The much-talked-about TV show Adolescence, which explores a teenage murder fuelled by social media toxicity, is encouraging calls for a social media ban, or at least regulation, in many countries. Actor Faye Marsay, who plays Detective Sergeant Misha Frank in the Netflix drama, has backed calls to stop children under the age of 16 from having social media accounts.

Equally problematic are artificial intelligence chatbots. According to a New York Times report last week, Google plans to roll out its Gemini artificial intelligence chatbot for children under 13 who have parent-managed Google accounts. It is being considered a push by tech companies to attract young users with AI offerings.

What action is being taken around the world to curtail children’s access to social media?

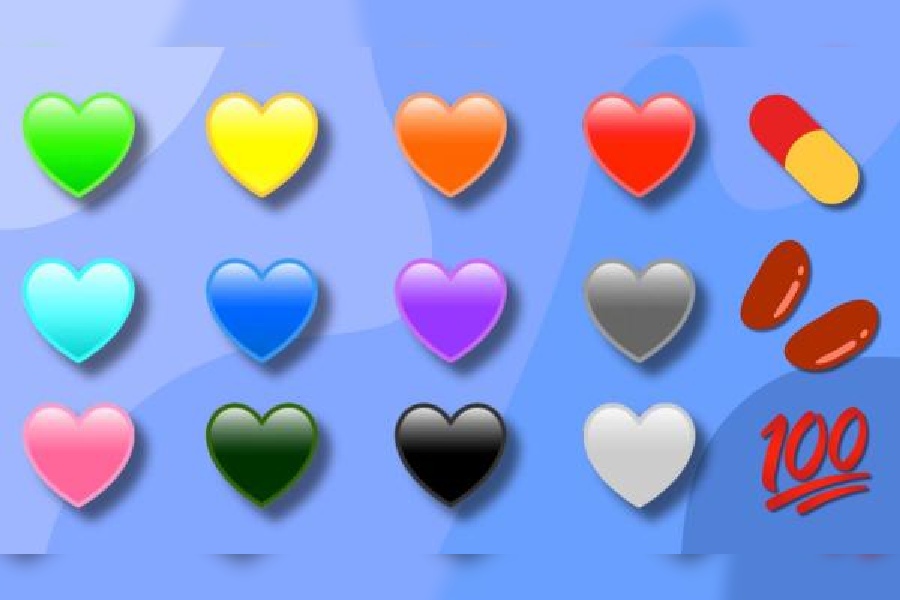

A collection of emoji discussed on Adolescence Collage: Getty Images

ADOLESCENCE EMOJI

• 100 emoji: On the show, the ’80/20’ rule is discussed. The character of Adam Bascombe says: “Eighty per cent of women are attracted to 20 per cent of men. Women, you must trick them because you’ll never get them in a normal way. Eighty per cent of women are cut off... she’s saying he’s an incel (a portmanteau of ‘involuntary celibate’).”

• Red pill: Adam talks about the ‘red pill’ to his dad Luke. “The red pill is like: ‘I see the truth.’ It’s a call to action by the manosphere.” The manosphere is a collection of websites, blogs and online forums that promote masculinity and misogyny while opposing feminism. The ‘red pill’ is borrowed from the film The Matrix. It now represents awakening to the ‘truth’ behind gender dynamics.

• Heart: Adam talks about what different colours of heart means to youngsters: “Red means love, purple — horny, yellow — ‘I’m interested, are you interested’, pink — ‘I’m interested but not in sex’, orange — ‘You’re going to be fine’. It all has a meaning. Everything has a meaning.”

Australia: A defining moment

Australia has put in place one of the world’s most restrictive social media laws. It bans children under 16 from using platforms like TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram.

Last year, the country’s Internet regulator, eSafety, found that more than 80 per cent of Australian children aged eight to 12 use social media or messaging services that are meant for over-13s. The platforms that were examined for the study were Discord, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Snapchat, TikTok, Twitch and YouTube.

The law gave birth to a framework that can be replicated in other countries. The legislation puts the onus on social media companies, which could be fined for systemic failures to prevent underage access.

Opposition came in the form of Elon Musk, the owner of X (formerly Twitter), who called the law “a backdoor way to control access to the Internet by all Australians”. In a submission to the Australian parliament, X said it had “serious concerns as to the lawfulness of the bill”.

Even Snap, the parent company of Snapchat, didn’t side with the ruling. The Guardian reported the company saying: “Many experts have highlighted the significant unintended consequences of this legislation, notably that it could deny young people access to valuable mental health and wellbeing resources, while potentially driving them toward less regulated and more dangerous online spaces than the mainstream, highly regulated platforms covered by the bill.”

Teen accounts and age verification

In India, there are no specific legal restrictions on protecting children from online harm. But earlier this year, Meta expanded its teen accounts feature on Instagram to India. The protections for such an account involve who teens interact with, the type of content they are exposed to, and how they manage their time on the platform. The safeguards are turned on by default, and for users under 16, any adjustments to make settings less restrictive would require parental approval.

To help manage time spent on the platform, teens will receive notifications “prompting them to exit the app after 60 minutes of daily usage”, said a Meta statement. Also, sleep mode will be enabled between 10pm and 7am, muting notifications and automatically sending replies to direct messages overnight.

The challenge lies in how effective age verification measures can be. Instagram said that “additional verification steps will be required in certain situations”, like when someone attempts to create an account with an adult birth date.

On the issue of barring children under age 13 from using social media, the Supreme Court of India, in April, said “it’s a policy matter” and told the petitioner’s counsel to “ask Parliament to enact the law”.

The US has had the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) for a long time, requiring parental consent for websites to collect personal information from children under 13.

When former US surgeon general, Dr Vivek Murthy, announced last year that he was planning to push for a mental health warning label on social media platforms, he was met with cheers from many parents and teachers, but most tech companies remained indifferent.

Even with some basic regulations in place, age verification remains an issue even in the US. Meta, Spotify, Garmin, Match, and others are lobbying that age verification should be the responsibility of app stores, and not the apps themselves.

It will save the apps from the work involved in age verification. Google, for its part, says Meta is trying to “offload” its responsibility to keep kids safe. Utah in March became the first US state to enact a law requiring app stores to verify user ages and obtain consent from parents before minors can download or purchase certain apps. Lawmakers in the House and Senate are planning to introduce similar legislation in the coming months.

In 2023, China floated the idea of limiting daily smartphone screen time among children to two hours. But the rules may have deep implications for companies such as Tencent and ByteDance, which run some of China’s biggest mobile apps.

Look towards Europe

The push for legislation around children’s access to social media is particularly strong in Europe. In 2023, France passed a law requiring social platforms to obtain parental consent for minors under 15 to create accounts. Last year, a report by experts commissioned by president Emmanuel Macron, recommended stricter rules, including banning cellphones for children under 11 and Internet-enabled phones for those under 13.

In October, Norway said it would increase the minimum age limit on social media to 15. The Norwegian prime minister, Jonas Gahr Støre, conceded it would be “an uphill battle” but said politicians must intervene to protect children from the “power of the algorithms”.

In Italy, children under the age of 14 need parental consent to sign up for social media accounts, while no consent is required from that age upwards.

Denmark will ban mobile phones in schools and after-school clubs on the recommendation of a government commission that found that children under 13 should not have their own smartphone or tablet. The minister for children and education, Mattias Tesfaye, told Politiken: “There is a need to reclaim the school as an educational space, where there is room for reflection and where it is not an extension of the teenage bedroom.”

Screen-time control

The pandemic highlighted the screen-time issue. Educators and psychiatrists are continuously stressing on educating children and young people about the safe use of Internet/social media. For this to happen, adults also need to be aware of the world of social media and influencers; ignorance is not an option.

Former England football manager Gareth Southgate, delivering a lecture in March, warned about the dangers of “callous, manipulative and toxic influencers” and demanded better male role models.

There are a few tools you can use to control screen time. For example, Apple’s Screen Time is a free set of parental controls built into the iPhone’s operating system. It allows parents to manage their child’s iPhone or iPad remotely, curb access to the phone at bedtime, and set limits on how much time a kid can spend on specific apps, on categories of apps, or generally on the phone.

Google Family Link is a free app to manage their child’s Android phone. Parents can limit how much time their child spends on the phone, schedule the phone to be inaccessible at bedtime, and block the use of individual apps, as well as set time limits for individual apps.

Perhaps the question parents need to discuss with their children is has social media improved lives and do we know the boundary between reality and what’s on social media?

Psychiatrist Dr Jai Ranjan Ram in his column in The Telegraph wrote: “If you are concerned about excessive screen time, express concern, not anger. Do not humiliate. There is a difference between voicing criticism and resorting to humiliation.”