I am often reminded of a song by one of my favourite reggae bands, UB40, when I am asked: “Doctor, how much can I drink?” The song Higher Ground has a line: The more I learn, the less I know about before.

When I was training to be a psychiatrist in 1990, it was widely thought that a glass of red wine was actually good for health. The amount of alcohol that was considered safe to drink every week was higher compared to what we now believe in 2025. With time, I have learnt more and realised how little I knew earlier.

The consensus belief in 1990, as per guidelines, was that men can drink up to 21 units of alcohol per week and women can drink 14 units per week. I gave the same advice to my patients. Now, I wonder how many people I have misguided, including myself.

One of the perils and wonders of modern medicine is that it falsifies previously held knowledge, and therefore keeping yourself updated about the ever-changing developments is mandatory for doctors. And so, when someone asks about safe drinking, I find myself pausing, searching for an answer that is both evidence-based and compassionate.

There are two questions about drinking that many doctors come across regularly. They are: “Is it safe to drink?” and “How much can I drink without harming myself?’ These are fair and extremely apt questions, as many of us enjoy social drinking. The problem is that the answers have been muddled by a whirlwind of changing advice from health experts over the years. For decades, we have heard that a little alcohol might help the heart, only to be told there is no safe amount at all. This flip-flopping has left many of us, including medical professionals like me, confused about what to advise.

Is a little alcohol good for your heart?

Back in the 1990s, many believed a daily glass of red wine could protect your heart, thanks to the so-called “French Paradox” — the idea that French people had lower heart disease rates despite a rich diet, possibly due to wine. But fast-forward to 2025, and the idea of “healthy drinking” is rejected. The consensus opinion has now shifted because older studies suggesting heart benefits were flawed. Older research compared moderate drinkers to non-drinkers without accounting for things like income, exercise, or diet — factors that made moderate drinkers seem healthier.

Newer research, like a 2023 study published in a prestigious medical journal, JAMA Network Open, found no real survival advantage from moderate drinking. So, the verdict? A little alcohol is not the heart-saver we once thought. The belief that alcohol in moderation is protective to the heart is now known to be erroneous.

Sadly, the buck does not stop there. The World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2023 clearly said that there is no safe level of alcohol. Even small amounts, like a weekly glass of wine, increase risks of cancer and other health issues, outweighing any debatable heart benefits.

The other major health organisations around the world have reached similar conclusions.

American Heart Association (AHA, 2025): The AHA says any heart benefits from moderate drinking are tiny and likely due to other factors, like a healthy diet or lifestyle. If you don’t drink, don’t start thinking it’ll help your heart.

World Heart Federation (2022): Recommends avoiding alcohol altogether for heart health, as the evidence for benefits is weak.

US Dietary Guidelines (2020-2025): Suggest that even ‘moderate’ drinking (up to one drink a day for women, two for men) doesn’t significantly improve overall health.

So, sadly and much to the disappointment of many of us, there is no ‘safe’ amount of alcohol that can be consumed without damaging health. This reality brings me to the next question. If there is no safe amount, how much alcohol is ‘okay’ to drink?

Health authorities now take a cautious approach, urging people to drink as little as possible.

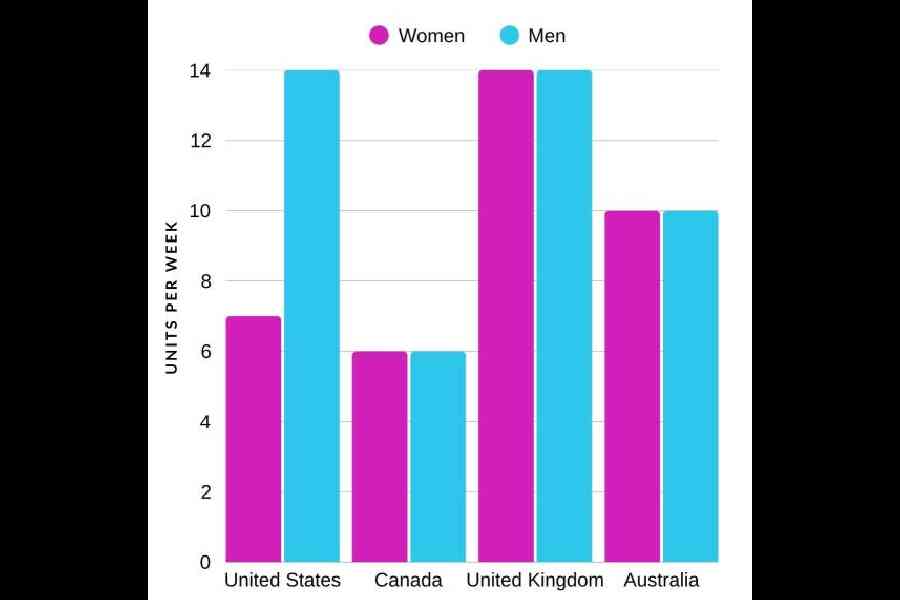

Here is what ‘okay’ looks like in 2025, measured in standard drinks (one unit is about a 330ml beer or 100ml glass of wine, or 30ml shot of spirits, containing ~10–14g of alcohol):

US: Up to one unit a day for women (seven per week) and two for men (14 per week) but less is better.

Canada (2023): Very strict — two units or fewer per week is low risk, three to six is moderate risk, and seven or more is high risk. No more than two units at once to avoid injuries.

United Kingdom: No more than 14 units per week (for both men and women), spread over at least three days, with alcohol-free days.

Australia: Up to 10 drinks per week for both genders, with no more than four drinks in one sitting.

WHO: No specific limit, just a clear message: The less you drink, the better.

Certain groups — pregnant women and people with liver disease — should avoid alcohol entirely.

The takeaway? Drinking less is always safer, and zero is best. A real challenge many mental health professionals face is trying to convince a heavy drinker to give up alcohol. Many of us are in denial that excessive drinking of alcohol causes multitudes of life-threatening illnesses, which at times can be fatal. Cirrhosis of liver is probably the best known amongst them, but it is definitely not the only one.

Many of my patients tell me they have relatives or friends who have been drinking for years and have not developed cirrhosis of the liver. They use this logic to justify that they, too, will not develop cirrhosis.

It is a valid observation, and it raises an important question: Why do some heavy drinkers develop cirrhosis, while others do not? The answer lies in a mix of biology, lifestyle, and even a bit of luck. Let me break down the key factors that determine whether heavy drinking leads to this devastating disease, so one can better understand the risks and make informed choices.

What is cirrhosis?

Cirrhosis is the liver’s cry for help after years of damage. The liver is a remarkable organ — it detoxifies harmful substances, produces vital proteins, and stores energy. But heavy drinking overwhelms it. Alcohol is metabolised into toxic byproducts, like acetaldehyde, which inflame and scar liver tissue. Over time, this scarring (fibrosis) builds up, replacing healthy liver cells and impairing function. If untreated, cirrhosis can lead to liver failure or liver cancer.

However, it is true that not every heavy drinker ends up with cirrhosis. Studies suggest that only 10–20 per cent of chronic heavy drinkers develop this condition, even after decades of excessive alcohol use. So, what makes the difference? Several interacting factors, like the amount of alcohol consumed, the genetics of the individual and other co-existing health conditions of the person, matters.

Some of us inherit genes which make our livers less efficient in clearing the toxic byproduct of alcohol. They are more likely to develop cirrhosis. Several variables play a role, and they interact in complex ways. Our genes also decide how the liver repairs itself or fights inflammation. If our genes make our liver less efficient at healing or more prone to scarring, we are at a higher risk.

In addition, our gender and body type matter. Women are more vulnerable to alcohol-related liver damage than men. This is because women generally have less body water and lower levels of alcohol-metabolising enzymes, meaning alcohol lingers longer in their system, causing more harm. Women also tend to develop cirrhosis at lower alcohol doses and in less time than men.

Body weight and fat distribution play a role, too. People with higher body fat may process alcohol differently, and obesity itself is a risk factor for liver damage. Previous viral infections which cause hepatitis make the liver more susceptible.

Our lifestyle can either protect or harm our liver. A healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins supports liver repair, while a diet high in sugar or processed foods adds stress. Smoking, often paired with heavy drinking, increases inflammation and cirrhosis risk.

If I am honest, luck does play a part in deciding whether someone develops cirrhosis or not. However, that does not give us a licence to drink beyond limits on the assumption that we all will be lucky. It is as safe as playing Russian roulette.

What can we do?

IF YOU DO NOT DRINK: Do not start thinking it will help your heart. Exercise, a good diet, and not smoking are far better options to keep our hearts healthy.

If you drink: Aim low — two drinks a week (Canada’s low-risk level) is safest. Spread drinks out, avoid binges, and take alcohol-free days.

Know your risks: Women face higher risks at lower amounts. If you have health issues, skip alcohol.

Talk to your doctor: Get personalised advice, especially if you are unsure about your drinking habits.

Dr Jai Ranjan Ram is a senior consultant psychiatrist and co- founder of Mental Health Foundation (www.mhfkolkata.com). Find him on Facebook @Jai R Ram and on Instagram @ jai_psychiatrist