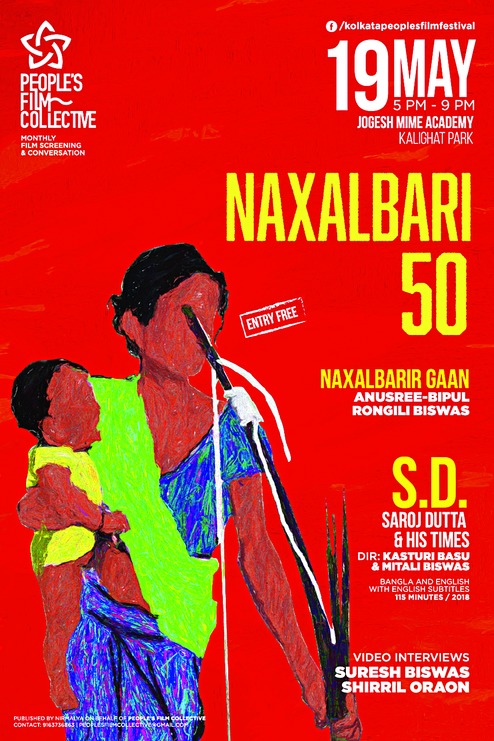

The auditorium of Jogesh Mime Academy in south Calcutta was packed with people that Saturday evening. The posters outside - the same that adorned many walls of the city - were a flaming red and announced, "Naxalbari 50". The Naxalbari peasant uprising broke out in the summer of 1967, and "Naxalbari 50" is part of jubilee observations rolling out since last year.

The programme was two-fold. The first part, musical - Naxalbarir Gaan or a showcasing of songs written in the course of the peasant movement. The second was the screening of a film - titled S.D. - on the missing Naxal protagonist Saroj Dutta.

"As a prelude to the film, we decided to travel back to those tumultuous times with songs from those times," says Kasturi Basu, director of S.D. and a member of the People's Film Collective (PFC), which organised the event. She continues, "People can easily relate to songs. We brought on stage those people who have kept the songs of Naxalbari alive."

On stage was a woman in a white Dhakai sari, standing upright and singing to the accompaniment of a flute and a madol, an indigenous drum. In her raspy voice, she sang in Oraon and Sadri, tribal languages spoken in many parts of eastern India, including the Darjeeling hills.

The lyrics ran thus: Sor sor sor sor hawa aai/Laal jhanda uri phar phar ki/Ladhai ki maidhaan/Aaj chala kisan, chala majoor nikalila... Her pitch rose and fell and her voice quivered like an ancient bird. The beats were reminiscent of a folk song.

The singer, Rongili Biswas, is the daughter of Hemango Biswas, singer and composer from the 1940s. Biswas was an active member of the Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA) - the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India - which was formed against the backdrop of World War II and the Bengal famine of 1943. Some notable members of the group were Prithviraj Kapoor, Balraj Sahni, Ritwik Ghatak, Utpal Dutt, Salil Chowdhury, Pandit Ravi Shankar and Jyotirindra Moitra.

That day there was little scope for conversation, but the day after Rongili speaks to The Telegraph about the " ajasra" or countless protest and folk songs she has curated and archived over the last eight years. These include Naxalbari songs as well. She clarifies, "My father did not compose songs for the Naxalbari andolan. But they were part of his collection."

Biswas passed away in the late 1980s. Rongili shows us a book written by her father on the socio-cultural history of Bengal and that has some songs. She also talks about his letters and diary entries on songs and their backstories. She tells us about the songs she sang that day at the mime academy.

" Sor sor sor sor hawa aai was originally sung by Naxalbari peasant Shukra Oraon and was recorded by Utpal Dutt for his play Teer or The Arrow which is about the beginnings of the tribal-peasant movement of Naxalbari.

She also sang Bir Pradhana, Bir Pradhana/Darjeeling ko chia bari/Sarmayadarko thailo/Timlai lal salam chho... Written by Nepali activist Kalu Singh, this song is an ode to those who fought the tea estate owners of Darjeeling. Bir Pradhana was a tea garden labourer and the song is a tribute to him.

Rongili tells us the songs she learnt from her father and the songs she found in his collection were written by the leaders of the Naxalbari movement as well as by peasants.

The songs were created mostly by the peasants. The composers arranged these. The songs Rongili had picked that day were, at the time of the movement, sung at krishak sabhas or farmers' assemblies and protest meetings, and only later became popular with the masses.

Bipul Chakrabarti's performance was over by the time we had reached that day. He sang with his wife, Anusree.

The first song they sang, we were later told, was - Torai kande go. The song was written by Santanu Ghosh in 1967 and is about the troubled geography of the Terai - the name for the lowland areas of southern Nepal and northern India. It goes: Torai kande re/Jolche amar hiya/Naxalbari math jole/Sapto kanyar lagi ar/Khun dheleche hajaar chashi/Ektu jami chai/Nil kheter oi khunete khun/Meshalo Torai...

In a crowded coffee shop in south Calcutta we meet Chakrabarti two days after the event. He says, "The song reminds us about the struggles of the indigo farmers, the share-croppers' demands during the Tebhaga movement of 1946 [they were fighting to increase their share from half to two-thirds of the produce]."

He also sang Tor uttore giriraj Himalay written by Kamal Sarkar in 1969, Suresh Biswas's Ahalya go ma janani and Sagar Chakraborty's Phansidewar chashi badhu, both written between 1967 and 1969 and O Naxalbarir Maa - the last by Dilip Bagchi, sung in the Kamtapuri dialect of the Rajbanshis.

Chakrabarti tells us his story. He was 19 when he returned to Calcutta after a wandering childhood spent in different parts of Bengal. That was 1974. Calcutta was burning. Naxalites were being hunted down. College students, journalists, poets, singers, no one was spared.

He says, "I was depressed. Every day I would hear that one or the other youth from my locality had died, some were my friends. I remember how the police would come looking for Naxalites and attack innocent boys playing carrom in the clubs. They would slash the boards, pick up the youth randomly, question them, torture them. I was not a supporter but I did appreciate some of their activities and opposed some."

He tells us how he had once accompanied a friend and Naxalite to a meeting in Krishnagar. "Four or five people sat around and discussed ideologies, sang songs and wrote poetry. It is there that I learnt the song Tarai kande go."

According to Bipul, the term "Naxalbarir Gaan" cannot and should not be restricted to compositions from 1967 and thereabouts, but should connote every song composed thereafter and speaking to the Naxal cause.

That evening at the dimly lit, old-fashioned, AC-less auditorium of Jogesh Mime Academy, there was barely any space to stand. The crowd was an uneven mix of young and old. A research scholar or two squatted on the ground and took copious notes. Some people made audio clips on their mobile phones.

"Naxal seems to be a forbidden word today. But the uprising is very important to the history of Bengal as the leaders were fighting for an egalitarian society," says Kasturi Basu. She asks, "How can one narrate the history of Bengal by deleting those years from collective memory."

But what would the young among the audience make of the references? Would those songs and narrations even resonate with them?

Chakrabarti tells us how after he sang his own song, Ei kada payer chhap - meaning, those muddy footprints - someone from the audience asked him if he was aware of the situation in Bastar, about the atrocities of the security forces on the people.

Chakrabarti says, "I told him I don't know about the specifics. But if you listen closely, it is all about the same thing - repression, repression, repression."