Picture Credit: Sudipta Bhowmick

The Old Kenilworth Hotel, the second oldest hotel of Calcutta, is being torn down. Only recently, the Fairlawn Hotel of Shashi Kapoor fame changed hands. That both properties were owned by Armenian families is no co-incidence, however.

On the atlas, the Eurasian Republic of Armenia looks like an ink splatter. Its area is slightly less than Kerala's. Its population, almost the same as Meghalaya's. It is then surprising to imagine that at some point, the people of such a tiny nation owned such a lot of Calcutta.

They were mostly merchants who went on to build some iconic structures that adorn the city today - The Oberoi Grand, Stephen House, Park Mansions, Queen's Mansion - two clubs, several schools of which only the Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy (ACPA) and Davidian Girls' School remain, and three churches. The Armenian Ghat on Strand Road was also built by them and so also was the ghat near the Kali temple at Kalighat. Structures such as the Victoria Memorial, Saturday Club and Dalhousie Institute were built with generous contributions by community members. In fact, entire neighbourhoods were named after them - Armenian Street, Sookias Street. The Lower Circular Road Cemetery houses 332 Armenian graves.

Ranajoy Bose of the Christian Burial Board, Calcutta, which looks after the cemetery, says , "Before the Marwaris came to Calcutta, the Armenians were the Marwaris of British India."

But why did they come to Calcutta? And before that, when did they get here first? There is a quarrel about the when. The epitaph on the oldest grave in the Armenian Holy Church of Nazareth in the bylanes of north Calcutta's China Bazar dates back to 1630. It belongs to one Rezabeebeh, wife of Mr Sookias. But the church itself was built in 1724.

Achinto Roy and Reshmi Lahiri Roy, co-authors of the paper, "The Armenian Diaspora's Calcutta Connection", quote existing literature on the Armenian diaspora to establish that Armenian merchants from New Julfa in Persia came to Bengal in the 17th century. In an email from Australia, Achinto tells The Telegraph, "The Armenians played a key role in securing the royal farman from the Mughals to enable the British to set up their trading posts in Calcutta. Armenian merchants played the role of middlemen in negotiating such deals as they had command over Persian - the Mughal court language - and were not subject to caste taboos, which made them comfortable dealing with people from other parts of the world."

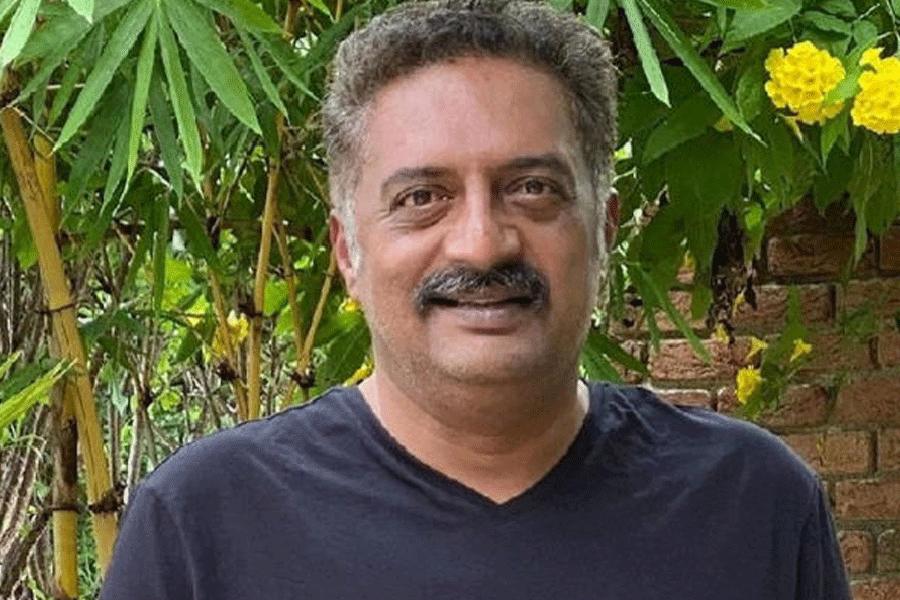

More than 300 years after the first Armenians arrived here, Andranik Matevosyan landed, under very different circumstances.

Picture Credit: Manasi Shah

Matevosyan was all of 11 when his mother broke the news. He was to be sent to Calcutta, a city 4,557 kilometres away from his home in west central Armenia's Ejmiadzin. Matevosyan had never been out of the country before, never been on a plane, scarcely ventured out of the neighbourhood even till then without parental supervision. But he had heard of Calcutta from television commercials about the ACPA. Something about it being one of the oldest Armenian educational institutions in the world.

On January 26, 2001, Matevosyan and 31 others were bundled into a flight and that was that. Two days, two time zones and three flights later - Yerevan to Moscow, Moscow to Delhi and Delhi to Calcutta - they arrived. "The first thing I remember was feeling hot. January, in Armenia, is chilling; temperatures drop to 3°C. From there, we were suddenly at 21°C in layers of warm clothes," says Matevosyan. It has been 17 years since. Matevosyan has stayed on.

He is not alone to have done so. His mates from that January day, Karen Mkrtchyan and Davit Gevorgyan, have not left either. Mkrtchyan graduated in German Studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, and Davit is pursuing a programme in Sports Management from George College, Calcutta.

It is not just about one year or one batch. Every few years, for the past two decades, there has been a steady flow of Armenian students from Armenia, Iran, Iraq and other parts of India into Calcutta. The college - which seems to be the main draw and had witnessed an exodus with its student number falling to 1 in 1996 - currently has 85 young people in its registers.

The three batchmates do not dwell on the memory of being uprooted or the difficulties of adapting to a strange land beyond the essentials - spicy food, strange language - but leafing through the 2015-16 yearbook, reading the accounts of the students, one gets a sense of the enormity of the shift. Almost all of them are about missing family and home, but they also articulate career dreams - becoming an architect or a lawyer. Reading these, it is not difficult to imagine working-class parents in a faraway land steeling themselves to take a giant leap of faith, only to secure the future of their young.

But it is still not clear how one vintage institution can inspire such a huge move and if it is at all related to those 16th century traders.

Talking to various community elders and the Armenian diaspora experts, this is what emerges - previous generations of wealthy Armenians have created a system that ensures most Armenians do not have to pay for their education in India.

Take the case of Sir Catchick Paul Chater, who was born to a family of Armenian merchants in Calcutta in 1846 and later went on to become a business tycoon of Hong Kong. He continued to plough back generous donations to the city of his birth and for his people here. Co-ordinator of ACPA Armen Makarian tells us, "La Martiniere was in a grave financial situation at one point. That is when Sir Chater stepped in as a benefactor and his generous contributions have been the reason why Armenians get full scholarships to study here, even now."

Meritorious students of the ACPA are, in fact, sponsored by the Armenian church and the college to continue higher studies in India in any stream of their choice from any university in India. Says Makarian, "Whenever Armenians leave the country, they submit their property related papers or money to the church. The church uses this corpus to bring students and pay for their education."

In fact, the television commercial that got Matevosyan down here in the first place was by the governing body of the Armenian Apostolic Church - Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin - which is also in charge of the college. And Mkrtchyan's mother was alerted by church authorities in Armenia.

It does not end with the college and grants. The community has developed certain oases of familiarity in this alien geography to help the youth adapt. Matevosyan tells us about the Bara Club on Park Street and the Armenian Sports Club near Red Road. He says, "We gather there to sing, dance and eat. Every January 6, we celebrate Armenian Christmas at the sports club. Church on Sundays is another major social mixer."

While a lot of young people returned to Armenia and Iran - where Armenians are the biggest minority community - after finishing school, and many more moved on to the US, France, Australia, a decent number stayed back in India.

Another such construct of Armenianness is rugby. It is a known fact that all Armenians in Calcutta are die-hard rugby enthusiasts. But in the 2011 documentary, My Armenian Neighbourhood, owner of Old Kenilworth Hotel and coach of the Armenian College team, David Purdy, tells filmmaker Samimitra Das that Armenia is by no stretch a rugby playing nation. He says, "Before Armenians come to Calcutta, they are not rugby players. They learn it in the Armenian College."

But this was not how it was in the interim years - in the run-up to Independence and immediately after. The 92-year-old Sonia John has seen and lived the denouement. She has a different story to tell when we meet her at her Ripon Street residence in central Calcutta.

John, who married into the family that owned the erstwhile Continental and Carlton hotels, came to India in 1931 from Shiraz in Iran when she was only five. "My grandmother bought me here at the request of my father who had studied here. I came here and joined the Calcutta Girls' School and never saw my father after that. He died of pneumonia when I was 11," she says, her old eyes mirroring that child grief.

John had a difficult time at school because she could not speak anything other than Persian and Armenian. Things changed for the better when she joined La Martiniere, where she met other children from the community. "A lot of Armenians also taught there," she adds. And in 1957, when she returned to Calcutta after higher studies in Delhi, and a couple of teaching stints in the city, she opened a private school herself.

After Independence, things changed. Once the British left, the Armenians experien-ced for the first time a certain kind of racial animosity. Says Makarian of ACPA, "The Armenian community was here for business, so when business suffered they left the country - went to Australia, the UK, other places. During that time Armenia was under the USSR, so people couldn't go back to Armenia either."

But the karmic wheel turned again and the Armenians were back in the city at the turn of the century. Today, Matevosyan holds a job here in the retail sector. Mkrtchyan is taken for a Himachali or Kashmiri and prefers it that way. Gevorgyan has developed a taste for spicy food.

As Sonia John puts it, "Armenians basically are survivors." Now we know.