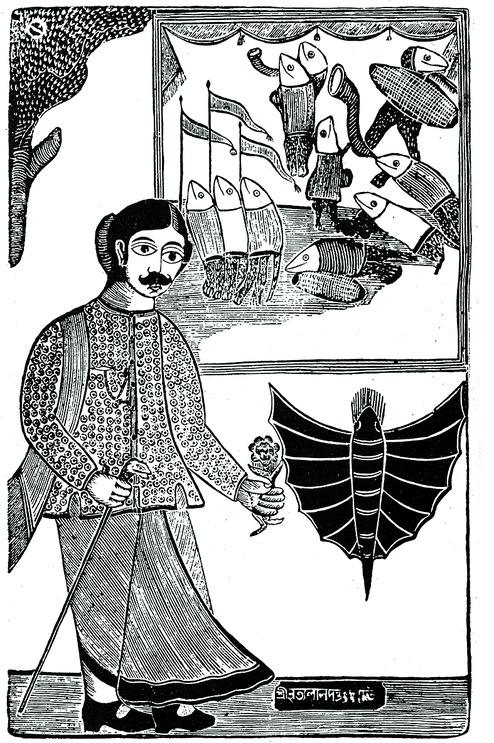

Pictures courtesy: Ashit Paul

Victoria Memorial's Albert Hall. The last day of April. A talk titled "19th Century Swadeshi Art in Bengal: woodcuts, woodblocks and lithographs". The discourse and the documentary screening preceding it are distillations from an exhibition underway at Victoria Memorial and curated by artist Ashit Paul. The show will travel to the National Museum, Delhi, soon.

Paul had also put together another 19th century art show in Delhi last year, but that focused on rare oil, oleographs, litho paintings and prints of the pre-Bengal School.

That day at Victoria Memorial, when the documentary started to play, it was the content that followed the colon in the title to his talk - woodcuts, woodblocks, etc. - that seemed to occupy screen space.

A fortnight later at his residence in southwest Calcutta, Paul tells The Telegraph, "My focus has been woodcuttings - illustrations, advertisements, and ads and illustrations of gods and goddesses in panjikas (almanacs) - from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century."

But we were more intrigued by the "swadeshi" bit. What did he mean by swadeshi art? Patriotic art?

Not necessarily, says Paul, and launches into a bit of art history. "Till the mid-19th century, the only school of art in Bengal was the Kalighat ' pat' art. Knowledge of the art form was passed down from one generation to another in artists' families. Other artists would imitate British themes and techniques. Wood and metal engraving were already being used by the British. In 1816, the first Bengali book with illustrations, Annanda Mangal, was published. It had two metal carvings and three woodcut illustrations, but we find only one artist attribution, Ramchand Roy. Here is a native author, a local story, a native publisher, a native illustrator, nothing British. So this art is 'swadeshi' in that sense, too."

According to Paul, woodcutting was not a traditional art form. He says, "The technique was used in the sari industry, but its evolution as an art form was entirely need-based. Publishers felt the need to illustrate books. And woodcutters were trained for the task."

He talks about how the pat artists eventually graduated to making litho prints and filling in colours to meet evolving demands. "It dawned on the woodcutters that they, too, dealt in outlines (which is what the litho prints were about). So, instead of limiting themselves to carving for book illustrations, they could carve on larger blocks of wood and reproduce copies for commercial gain. Thus came large display pictures - and they found place of pride in the homes of babus. These illustrations dealt primarily with social issues and satires, especially on the ' babu' culture. This transition was not conditioned or through training. So it was 'swadeshi' in that way, too."

Paul hands us a booklet published by Vic-toria Memorial Hall in collaboration with Akar Prakar, the Calcutta-based art gallery. It has images of prints, some coloured, mostly black-and-white. Some of the most eye-catching ones - with titles such as Lobster with Fish, Cat with Lobster - come sans artist names.

We keep flipping the pages - advertisements, lithographic prints. The last category shows some fairly elaborate drawings. There is one that is apparently of Shiv, rays emanating from his third eye and a serpent tangled in his dreadlocks. Behind him there is an embracing couple and a kneeling woman. One can see the Himalayas in the background and a couple of coniferous trees and behind them a youth with a flowery bow. It is titled The Oriental Cupid in Flames and dated 1878. Yet again no artist credit, but it does say Calcutta Art Studio.

Paul tells us that the Calcutta Art Studio was established in 1878 by Annadaprasad Bagchi and two others - all products of the Art School, which is now known as the Government College of Art and Craft. This was the first Indian studio in this part of the country. "Bagchi's motto was that though I have learnt from the British, I shall work with Indian motifs and styles," says Paul.

The studio provided the nouveau Art graduates the opportunity to print their works, make them easily available. But what of all those anonymous artists? Was their anonymity an accident or someone's design?

Says Paul, "As far as swadeshi art is concerned, I don't yet have an answer to that. Patuas never signed their scrolls or mentioned the place of production, they still don't. It's different with woodcutting, though. Blocks usually have names of carvers engraved but that doesn't necessarily mean they were also the designers of those pictures. They were, in fact, catering to the requirements of the authors or publishers."

And, then, there was rampant plagiarism. "I have found a picture of Durga, along with the name of the engraver, in one edition of a panjika of a particular publisher. The same image appears in another panjika but with a different attribution," says Paul. Not all of it was the doing of plagiarists though; many a time it was about plates being stolen from a printing press and landing up with others.

Paul talks about another possibility too. "Say four or five panjikas were being printed at one particular press. The printer or the manager of the press would use the same image in two or more of them arbitrarily. I have also come across pictures that had appeared in some panjika or the other being used to illustrate Barna Parichay kind of children's books. What mattered more was the appeal of the picture, not who the maker was."