|

Vinod Scaria is a doctor and Manoj Hariharan studied biology in university. The two researchers, however, have spent the past several months discovering high-speed computers and software in a laboratory in New Delhi. And they have pitted their newly-acquired skills to unravel the mysterious “peace pacts” between some people and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that causes the dreaded and incurable AIDS.

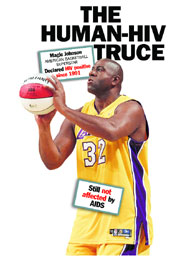

The human - HIV truce in some, albeit rare, is no secret. The first signals surfaced during the 1990s ? about a decade after the discovery of HIV ? when doctors realised that a tiny fraction of HIV-infected people remained in good health years after infection. When doctors track HIV-infected people over many years ? whether it’s commercial sex workers in Kenya or haemophiliacs in the US ? they typically find some “lucky individuals” whose immune systems remain intact despite their exposure to HIV.

Scientists believe that the explanation for this resistance to HIV displayed by some people lies in their genes. The HIV uses molecular gateways on human cells to gain entry into them. Variations in these gateways might block the entry of the virus into cells.

|

| GENE TRACKERS: Hariharan and Scaria at work at the IGIB, New Delhi. |

Now Scaria and Hariharan, guided by the director of the Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (IGIB) in New Delhi Samir Brahmachari, have used software to unravel another piece of the peace pact puzzle. They have predicted that tiny segments of genetic material called microRNA in humans have the potential to deactivate a crucial HIV gene that the virus needs to replicate after it has invaded the body.

The molecules that make up genetic material are DNA and RNA. The standard decades-old dogma of biology has been that DNA makes RNA, which makes proteins. However, microRNAs are a relatively new concept in biology that emerged only in the mid-1990s. These short genetic sequences of RNA do not code for proteins. Instead, they function as genetic switches to turn protein-coding genes on and off.

Over the past two years, scientists have been building a database of all microRNAs discovered in all organisms, including humans, and the entries are growing month after month. The search has turned up more than 300 microRNAs in humans alone. They are believed to play a role in myriad processes ? from the creation to the death of cells.

Brahmachari, a biophysicist, coaxed his team to look at how microRNAs might interact with viruses. “Viruses expose their genomes completely to the host cellular machinery,” said Brahmachari. “It’s an opportunity for the host to target viral genome. MicroRNAs are intriguing. We wanted to find out whether they do something to viral genes,” he said.

Computational prediction

|

|

| Samir BraHmachari, Biophysicist (Top) and Shiv kumar, Research scholar |

As a first candidate, the IGIB picked HIV. Scaria and Hariharan used multiple software programs to study whether any microRNAs in the human body might interact with any of the HIV genes. Their number-crunching exercise revealed that five human microRNAs do indeed interact with four genes of HIV. Two of these microRNAs ? coded in the database as hs-mir-29a and hs-mir-29b ? interact with HIV”s nef gene. The nef gene is important for viral replication. When nef is deactivated, the virus cannot replicate.

“The computational prediction looked beautiful, but we need to establish that it is true through real biology,” said Brahmachari. He assigned the task to Beena Pillai, a scientist who joined IGIB after completing her doctoral programme at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. The first thing Pillai had to do was to show that the microRNA in question is indeed produced in T cells, the target cells of HIV. From raw data on microRNA expression in T cells generated by independent scientists outside India, Pillai extracted information that showed that not only was microRNA produced in T cells, the levels of the microRNA also varied from individual to individual. While it’s merely a hypothesis for the moment, Pillai said, such variations in the microRNAs might partly explain why some people react differently to HIV. In another set of experiments, Pillai and her colleagues showed that blocking the microRNA actually drives up the production of the nef protein.

|

|

|

| (From Top) Beena Pillai,Geneticist, Manoj hariharan, Computational biologist and Vinod scaria, Doctor |

A number of leading scientists believe that microRNAs will be part of explanations of viral infection and host immunity against viruses. “It seems completely possible that microRNAs could be involved in both HIV infection and HIV resistance,” said Scott Tenenbaum, a molecular geneticist at the University of Albany in New York. Tenenbaum and his colleagues last year produced fresh data showing that not all HIV-infected people become sick. He found that severe haemophiliacs with exposure during the early-1980s to infectious HIV- contaminated clotting factor concentrates through transfusions had low levels of immune responses, but remained negative and apparently uninfected. Reporting their findings in the Virology Journal, they said the study supports “the possibility of HIV exposure without sustained infection and the existence of HIV negative natural resistance in some individuals”.

In a paper published in the journal Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, the IGIB scientists said the study of differences in the microRNAs among HIV-infected persons as well as HIV-infected persons who have not developed any signs of disease over a long period of time could provide further insights into the role of microRNAs in the disease progression. Such studies could only be done through collaborations with doctors who have been tracking HIV infected people in India.

Non-progressors

If what the IGIB scientists have predicted through computational biology and preliminary laboratory studies is true, people who have not fallen sick for several years despite infection with HIV would presumably have higher levels of microRNA that can switch off the HIV nef genes. Doctors call such persons “long-term non-progressors”, a term to describe the lack of progression from just HIV positive to full-blown AIDS, a condition in which the viral population shoots up, immunity fades away, and opportunistic microbes take over to ravage and eventually kill the patient.

“Long-term non-progressors are seen all over, and they should be present here in India too,” said Ramesh Paranjpe, director of the National AIDS Research Institute in Pune, where doctors have been following up HIV infected patients for several years. “But this exercise started only in the late-1990s, and true non-progressors should have stable immune systems for at least 10 to 12 years after infection,” he said. At the IGIB, researchers say that if the findings are confirmed through the studies being planned now, it might be possible to design synthetic microRNAs and use them as therapy against HIV.