I've humbly realised that doctors aren't always indispensable. When I was three, a compounder - a doctor's assistant - allegedly saved my life. Dehydrated from severe dysentery, I was ashen and lifeless. My blood pressure was falling and I would soon lose my pulse. I needed fluids urgently. An experienced paediatrician could not get a line into my collapsed veins. When hope seemed lost, his compounder gingerly offered to try, and got fluids inside my veins on the first attempt. My pulse and colour returned and I lived to hear the tale from my mother.

So, on a recent trip to India, I was intrigued by Birju, a compounder in my ancestral village in Bihar, who the villagers revere like a doctor. After assisting a city physician for ten years, Birju had started his own practice. He has no formal training in healthcare. Even his education was partial - he left school at fourteen to help his father, who also was a compounder.

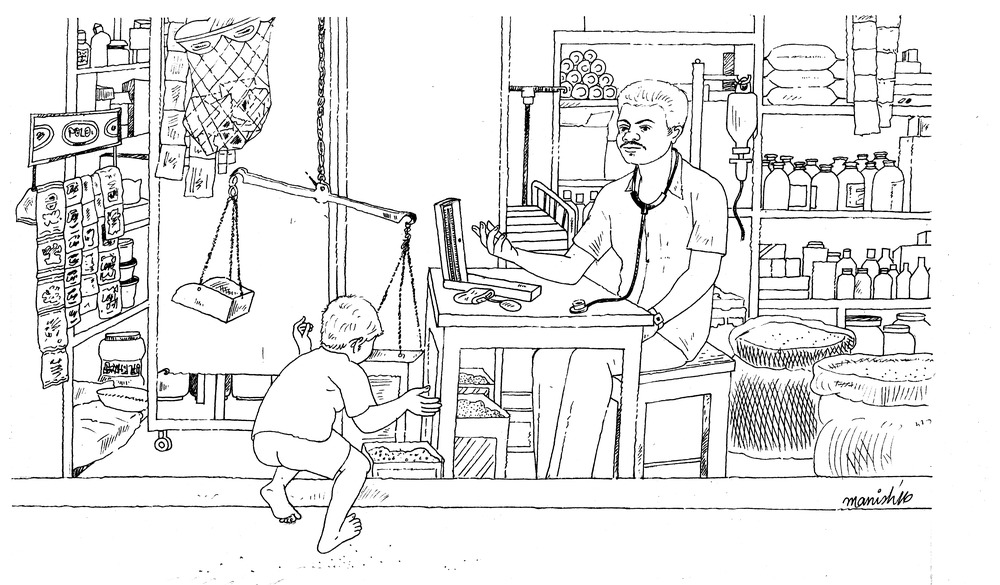

I wanted to see Birju practice his craft. So, I visited his clinic which is actually a shop. Birju sells stationery, conveniences such as shaving foam, and medications, which was just as well, as I needed Imodium to calm my angry Americanised bowel.

Birju's first patient was a child with belly pain, possibly from appendicitis. In Philadelphia, we exclude appendicitis using blood tests and CAT scans. Birju used a cheap and nifty test - observation. Glancing briefly at the child, Birju instructed him, " Kudo" (jump). The child began jumping. Birju then said "kudtai raho" (keep jumping). The child kept jumping and smiled uncertainly. Finally, he offered cake, which the child ate eagerly. Birju reassured the mother that the child had nothing serious.

When doctors suspect appendicitis they press the belly, looking for "rebound tenderness," where a patient hurts more when the belly is released, than pressed. Jumping is an ingenious way of uncovering rebound tenderness. If the child had even mild appendicitis he would have winced with pain. Birju has never heard of rebound tenderness. He has never read a medicine book. He learnt the "jumping test" from the physician he assisted. Early in our medical training we are all theory, no practice. Birju was the opposite, all practice, no theory, an apprentice in the purest sense.

Birju's next patient was a lady complaining of appetite loss and body aches. Birju, with attention to her modesty, pulled down her eyelids to look for jaundice, asked some perfunctory questions and, within a minute, decided that the diagnosis was beyond his pay scale. Birju's triage [order of treatment] is simple. He sends patients with acute conditions, which could kill the person in hours - such as water in the lungs - to nearby Bihpur, a small town with X-ray and other facilities, five kilometres away. He is good at spotting the seriously ill. No one has died at his doorstep. He sends patients with chronic problems to Naugachia, a medium-sized town with CAT scans and specialists. He sent the lady with body aches to Naugachia.

Just like a good doctor is supposed to do, Birju follows up on his patients. He saw the boy with belly pain the next day. During the cholera outbreak, Birju visited people in their houses to start them on fluids, and returned to ensure the drip still worked, and that they weren't over hydrated. His business model is simple. He charges patients for medication, but not the consultation or the follow-up. He gets a cut from the sale of medications and from referrals to physicians. In the US, Birju would be imprisoned for violating anti-trust laws and receiving kickbacks. In rural India, Birju's tight network lowers the costs for the villagers. The kickbacks feed his family.

Clayton Christenson, a Harvard professor, believes if healthcare is partly delivered by cheaper, but good enough, alternatives to doctors, such as nurses, which he calls "disruptive innovations," the costs can be reduced. I'm certain Birju has never heard of Christenson but he's an example of a disruptive innovation which has arisen because doctors are a luxury for the two-thirds of Indians living in villages.

The Indian Medical Association controls who practices medicine. Birju's practice is clandestine, at best. But if Indian doctors don't serve the villagers, they have no business regulating who does. Instead, the government should help village compounders better communicate with city doctors by, for example, buying them the latest smartphones.

As I was leaving, Birju advised, "When the angry American stomach calms down, stop taking the medication otherwise you'll have a silent Indian stomach." He was right.

Dr Saurabh Jha is associate professor of radiology at the University of Pennsylvania. Raised and educated in the UK, he is a native of Bihar and often visits there