Hiding inside every apple is a little bit of secret geometry. To reveal it, cut the apple sideways, straight through the core. There you’ll find five seeds in the shape of a star.

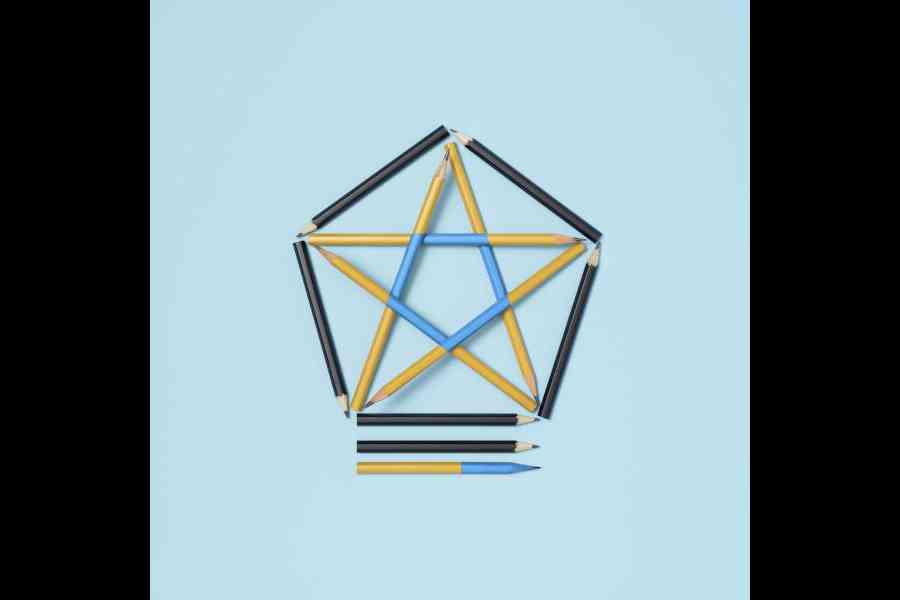

In its idealised form, this kind of five-pointed star is known as a pentagram. In mathematics, the pentagram is a poster child for “self-similarity”, a symmetry that’s like worlds within worlds. The shape contains infinitely many smaller and smaller copies of itself, like nested Russian dolls.

To see self-similarity in action, imagine connecting the star’s points with straight lines.

The newly created pentagon immediately calls attention to a smaller pentagon nestled inside the star.

A famous number known as the golden ratio describes the proportions of the smaller parts to the whole. The parts add up: a blue segment and a yellow segment, laid end to end, are exactly as long as a black segment. Or, small plus medium equals large.

Moreover, the parts are in the same proportion: medium is to small as large is to medium. That common proportion defines the golden ratio, which is approximately 1.618: 1.

In 1509, an Italian mathematician named Luca Pacioli ascribed cosmic significance to the golden ratio in his book On the Divine Proportion. The book included many illustrations by his friend Leonardo da Vinci, including a 3D shape (a dodecahedron) made from identical pentagons.

Years earlier, Leonardo had performed his own study of proportions, based on the theories of ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. This led him to draw an iconic image known as Vitruvian Man.

Did he hide the golden ratio in it?

This much we know: with his arms spread wide, Vitruvian Man fits perfectly in a square — his wingspan equals his height.

With arms and legs splayed, he also stands comfortably on the circumference of a circle, which his middle fingers extend to touch. At the centre of it all is his navel.

Leonardo’s handwritten notes specify many of the man’s proportions as fractions of his height.

“From the hairline to the bottom of the chin is one-tenth of the height of the man.”

“From below the chin to the top of the head is one-eighth of the height of the man.”And so on.

Yet nowhere does Leonardo quantify the location of the man’s navel. This omission seems surprising, given the navel’s centrality in his scheme.

Some commentators claim that Leonardo positioned the navel to divide the man’s height according to the golden ratio.

But Leonardo doesn’t mention the golden ratio, either in the drawing or in his notebooks.

In fact, a 2015 analysis by architect Vitor Murtinho found that the placement of Vitruvian Man’s navel does not quite comport with it. The man’s height in the drawing is 181.5 millimetres, and the height of the navel is 110 millimetres, for a ratio of 1.65-to-1. That’s close to the golden ratio (1.618-to-1), but surely Leonardo could have come closer if he’d meant to.

Is it possible that Leonardo really thought 1.65 was the correct anatomical proportion for a well-shaped human being? And what, in fact, is the typical number? Presumably, it falls on a bell curve — or should we say bellybutton curve.

As for what’s most desirable, proponents of the golden ratio insist on a divine proportion. The ideal navel should divide the upper abdomen from the lower abdomen, not in half but in a ratio of 1.618-to-1.

Indeed, a 2015 study published in the journal Aesthetic Plastic Surgery asked participants to select the most attractive navel position on digitally altered pictures of bikini models and found that the golden ratio was ideal.

On the other hand, a 2022 eye-tracking study in The Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, in which volunteers looked at digitally altered images of a female patient, found that a 2-to-1 ratio of upper to lower abdomen was more pleasing than the golden ratio.

Divine proportions? Meet diverse ones — they can be beautiful, too.

NYTNS