Punching in emojis and hashtags, we might pride ourselves in thinking we are singularly placed in history but we would be much mistaken. Across time and civilisations, human beings have improvised on signs and scripts to communicate effectively. Bahata Ansumali (in pic), a software technologist turned researcher, was in town recently for the Kolkata Literary Meet. Prasun Chaudhuri spoke to her about her work on the Indus Valley Civilisation script and symbols. Here are excerpts from

the interview.

Q In the recently concluded Chennai seminar on the Indus Valley Civilisation, where you were an invitee, Tamil Nadu chief minister M.K. Stalin announced a grand prize for anyone who can decode the script of the Indus Valley Civilisation. What is the Indus script and how was it used?

The roots of the Indus Valley Civilisation can be traced back to 7,000 BCE. Over the next three millennia, thousands of Indus settlements comprising cities, towns, craft-centric and agriculture-centric settlements were built, spanning almost one million square-kilometres of the northwestern part of the India-Pakistan subcontinent. Between 2,600 and 1,900 BCE, the economy became so complex that a section of merchants, artisans’ guilds and certain settlements came together to standardise taxation, commercial licensing and measurement systems. It is they who came up with a standardised mercantile script to communicate commercial administrative information.

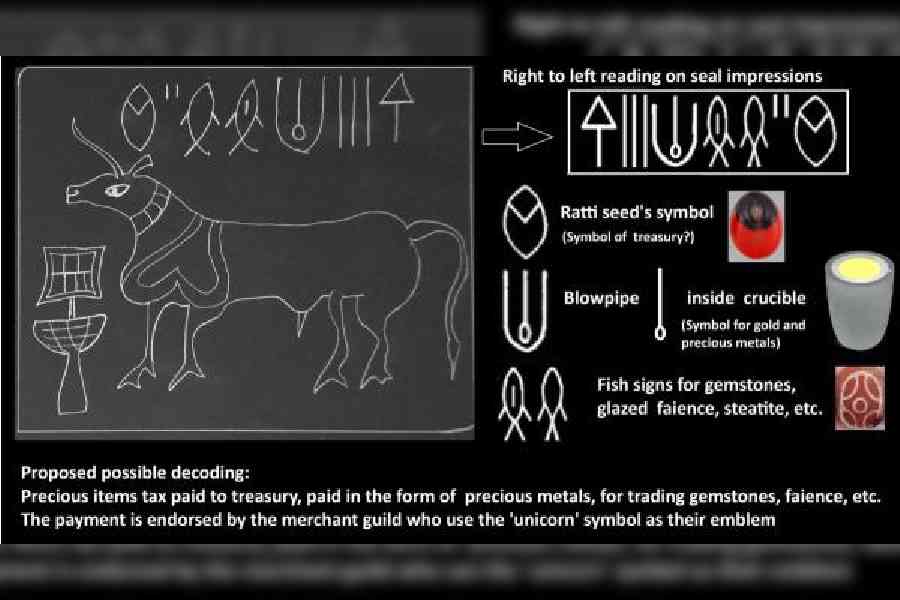

The Indus elite had controlled trade by building fortified cities with narrow gateways and a system wherein guards and tax-officers checked the incoming and outgoing merchandise, collected commodity-specific taxes and stamped small soft-clay tags using stamp-seals to endorse that traders had paid their dues. The stamp seals encoded types of taxes and licenses, names of taxed commodities and emblems of issuing authorities. Even traders from distant and linguistically diverse settlements could understand and accept this mercantile script of meaning-symbol, as it avoided language-based symbols most of the time.

Q Could you cite an example?

They used the symbol of a blow-pipe and crucible to denote gold and precious metal. They were important goldsmithing and metallurgical equipment, their use as the precious-metal symbol was acceptable to all communities of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Such crucible blowpipe-based symbolism for metals and metalsmithing was also used in Egyptian and Mesopotamian scripts, and in ancient Indian languages.

Illustration by Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay

Q Have you managed to decode any other symbol?

Yes. The Indus scribes used the symbol of the ratti, gunja or kunri- mani seed (Abrus precatorius) to denote the gold-measuring unit. The weight of the seed was the basis of their weight-system. Ratti is still used as the Indian equivalent of the carat, which is a measure for gold and gemstones. This symbol was mainly used in seals, and was also engraved on an Indus goldsmith’s tool excavated from Mohenjo-daro, possibly to denote the purity and/or weight of the gold alloy.

Q If the Indus script was largely non-linguistic, why did your Chennai paper talk about ancestral Dravidian symbolism?

Because, in order to express more abstract meanings, the Indus scribes sometimes used a mechanism used by many other ancient scripts, wherein the symbol of one easy-to-express word is used to denote another similar-sounding word whose symbol will be difficult to express pictorially. For instance, the Sumerian script used an arrow symbol to signify the concept of “life”. This is because in Sumerian language both arrow and life were pronounced “ti”. Since the Indus fish sign inscriptions were often engraved in seals found in jewellers’ shops and gemstone factories, I argue that the fish signs were related to gemstones, and certain other glazed precious commodities. In the Indian subcontinent, it is only in the Dravidian group of languages that the words for glittering things such as fireflies, stars, lightning, coins, gemstones and fish are coined from the proto-Dravidian root word “min”, which means shining, polishing, etc.

Q Do we have evidence to confirm that ancient Dravidian languages were spoken in the Indus Valley Civilisation?

There is ample evidence provided by archaeogenetic, linguistic, ethnohistorical and archaeological studies. I have also written about it in a paper published in the Nature group journal Humanities and Social Sciences Communications in 2021. The Indus word for ivory used across ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia, and the widespread Indus word for the toothbrush tree “miswak” was “pilu”. This was derived from the proto-Dravidian word for ‘tooth’. Currently, Prof. K. Rajan and his team are analysing more than 15,000 graffiti on pottery excavated from Tamil Nadu and exploring why some of the complex graffiti symbols are so similar to certain Indus script signs.

Q Can the Indus script ever be completely decoded?

With the data available at present, we can only partly decode the script. Imagine you have arrived from a distant planet and discovered traffic symbols at some spot. By correlating the features of certain signages with the location of those signages, you may understand some of them. But not all traffic symbols can be decoded without the help of a manual. Likewise, you would need a dictionary or an Indus document that has the same meanings written in the Indus script, and a known script. Rosetta Stone was such a document that helped decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Q Can’t some artificial intelligence (AI) system help in decoding the Indus script?

AI can definitely help, if we use it properly.