Four-year-old Pompa sat beside a flight of stairs leading to a pond in their ancestral house in Binodpur, a village in Sunderbans’s Kultali block, 100 kilometres south of Calcutta. She had been playing with a doll and also watching her brother Aritra, 13, who was enjoying a dip in the pond.

This was last July when the ponds were filled to the brim after the monsoon showers. The ambience was exhilarating, unlike the cloistered space of Pompa and Artitra’s rented apartment in Bansdroni, in the southern fringes of Calcutta.

After a while, Pompa noticed that her brother was missing. Panic stricken she started to wail. Alerted by her distress call, her mother, uncles, aunts and neighbours rushed to the pond. Says Aritra’s father Diptendu Bikash Dey, “Many of them dived into the pond, but they couldn’t find him anywhere.”

More than 10 minutes had passed and dozens of people from the surrounding area had arrived. Some of them were beating the water surface with sticks and chanting invocations to Goddess Sasthi, who is believed to protect children from danger. There were others cursing the evil spirits.

“Amid the chaos, my wife noticed bubbles emanating from a spot in the middle of the pond,” said Diptendu. Bubbles in such a scenario suggest a drowning person’s struggle to breathe.

Sukumar Halder, a marginal farmer, had heard the hullabaloo from a distance. He rushed to the spot and he seemed to know what was happening. He jumped into the pond, the very spot from which the bubbles were emanating. Within minutes he found Aritra lying at the bottom. He threw him over one shoulder and swam towards the shore. As he laid the boy down on the grass, Halder noticed that he had turned ashen. He touched Aritra’s wrist and felt a feeble pulse. He was not surprised that many superstitious villagers had come forward to practise their ancient voodoo technique: spinning the boy’s body in the air while chanting incantations.

He was well aware of the fact that the mumbo-jumbo had already killed scores of victims of drowning. So, he shoved them away, and assisted by two companions started applying CPR or cardiopulmonary resuscitation on the listless boy to prevent an imminent heart attack.

Litres of water were pumped out of his stomach. Halder told The Telegraph, “I was able to revive him within minutes and then arranged for oxygen support locally.” The nearest medical facility is 25 kilometres away. Diptendu arrived from Calcutta with an ambulance and drove him to a big hospital in the city. He added, “Doctors found remnants of pond muck in his lungs which led to a near-fatal infection. It took him about three months to recover.”

Aritra is the 10th person Halder has rescued. He said, “Another minute and he would have died.”

It turns out that Halder had been trained in life-saving skills at the neighbouring village of Baikunthapur by the Calcutta-based Child In Need Institute (Cini), a non-profit that works to promote health, nutrition, education and child protection. This organisation has forged a partnership with the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and global agencies such as The George Institute for Global Health (TGI), Australia, and the UK’s Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI).

Said Sujoy Roy, national advocacy officer, Cini, “We have been implementing a comprehensive programme to prevent child drowning. The programme includes rescue and resuscitation training of community members with lifesaving skills.”

So far, Cini has trained 2,500 volunteers like Halder who are ready to respond to drowning emergencies.

Child drowning deaths are a “silent crisis” in the Sunderbans, otherwise known for the beauty of its mangroves and for being a crucial habitat to a wide variety of flora and fauna, including the endangered Royal Bengal tiger.

An extensive survey carried out in the region — 19 blocks across two districts — from 2016 to 2019 by Cini, TGI and RNLI revealed that the area also has the world’s highest child drowning mortality rate. “Most children drowned in ponds within 50 metres of their homes when they were unaccompanied by their primary caretakers who were engaged in household work,” reads the survey.

Some children do get rescued, but only three out of 50 receive care from licensed doctors. According to Roy, drowning deaths, especially among toddlers are highly preventable through low-cost interventions.

He said that the crisis

remains hidden because most drowning deaths masquerade as “unnatural deaths” in the police files. For that matter, it’s not just in the Sunderbans. Usually, when the police investigate a drowning death anywhere in India, they typically file it as a case of “unnatural death” because drowning, while often accidental, can also be the result of foul play, suicide or negligence.

Besides, since many cases are not reported by the victim’s kin to the police, post-mortems are rarely conducted to officially confirm drowning.

To show me how rampant child drowning in the Sunderbans is, Roy took me around some of the households in Baikunthapur village. Most of the houses have multiple ponds attached to them. “Infants and toddlers often just walk into the water while chasing ducks or roaming around unattended. The little ones don’t consider ponds a threat,” said Roy.

In one of the households we — Roy and I — met a mother who lost her five- year-old daughter recently. We found the distraught mother beside a pond. She and her mother-in-law narrated the story of their loss. The girl had wandered out and slipped into the water, unnoticed. Said the mother between sobs, “I was busy cooking and my mother-in-law had gone to the market.”

In 2024, the World Health Organisation launched its first-ever Global Status Report on drowning prevention. It revealed that 3,00,000 people died by drowning in 2021; and 90 per cent of these occurred in low and middle income countries. Almost half of all drowning deaths occur among people below the age of 29 years, and a quarter occur among children under the age of five years. Children without adult supervision are at an especially high risk of drowning.

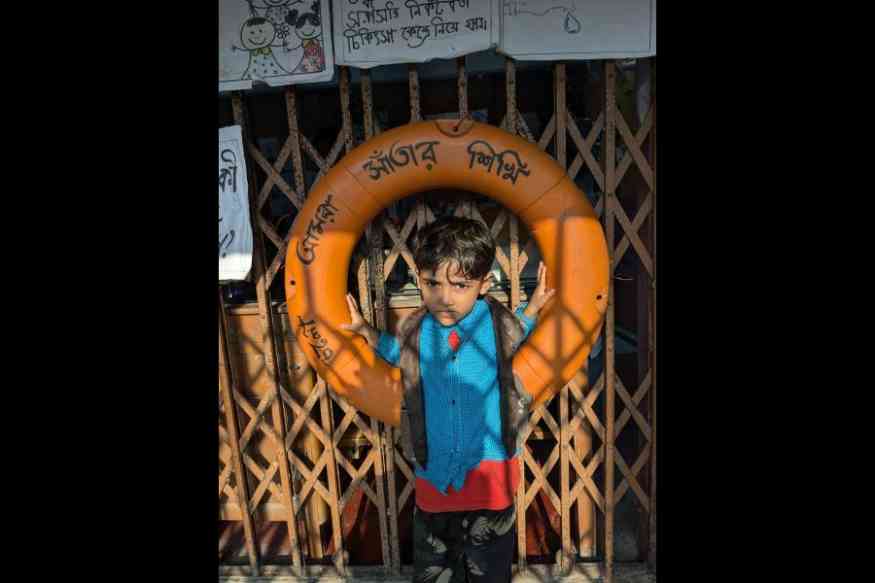

As a part of drowning prevention, Cini with the support of ICMR started a Kavach centre at Baikunthapur, a creche that offers a safe space for mothers to drop-off their children — from morning to afternoon — while they work, and support pond-based pools to teach children swimming and water safety measures.

In the pool next to the creche, children are taught to swim and trainers enact plays to recreate drowning scenarios and present ways to avoid risks to prevent it. Adult volunteers like Haldar are trained to be “first responders” in case of drowning emergencies.

Mriganka Mouli Das, 53, is a certified trainer who teaches children between 6 and 18 to swim in a scientific way and older people life-saving techniques. “It takes 12 classes spread over three months to learn the ‘float to live’ technique,” said Das.

In short: if you find yourself struggling in the water, the experts recommend you be calm, tilt your head back with ears submerged, and move your hands to help stay afloat. It’s okay if your legs sink, and you should spread your arms and legs to improve stability.

Apart from swimming lessons, Cini also conducts water safety education and advocates villagers to erect fences around ponds and impart water safety education workshops for schools.

“They have been playing a significant role in reducing drowning deaths among children through various interventions,” said Dr Manas Pratim Roy, assistant director general, ministry of health and family welfare, New Delhi. “Their work has been recognised internationally, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) showcasing their achievements across the world.”

Meanwhile, Aritra has decided to learn swimming at the Baikunthapur training pool and become a lifeguard like Sukumar Haldar when he grows up.