Scientists have announced their discovery of marine tubeworms and molluscs thriving at the bottom of two trenches in the Pacific Ocean at depths up to 9,533 metres, the deepest known occurrence of such life forms.

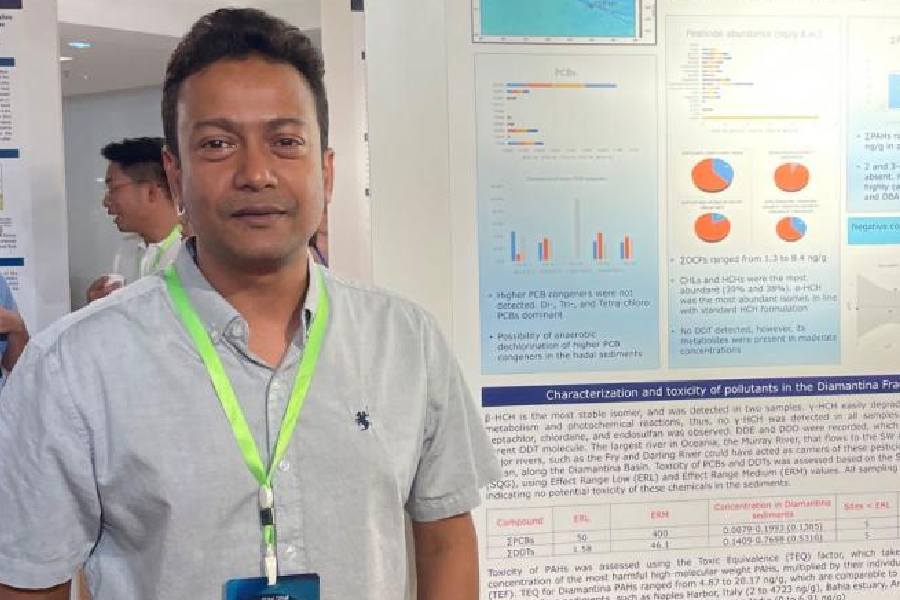

Indian geochemist Shamik Dasgupta was among the scientists who descended into the trenches in a submersible and observed the creatures living under crushing pressures, near-freezing temperatures, and total darkness — expanding the boundaries of where life can thrive.

The deep-sea discovery led by a Chinese-Russian team has revealed creatures that survive entirely on hydrogen sulfide and methane spewed from the seafloor, challenging the long-held belief that such life feeds on organic debris falling from above.

During 19 of 23 submersible dives into the Pacific’s hadal zones — the deepest and darkest parts of the ocean — in the Kuril-Kamchatka and Aleutian trenches — scientists observed flourishing colonies of multiple tubeworm and mollusc species at depths from 5,700 to 9,533 metres. Some colonies had thousands of tubeworms, each up to 30cm long, clustered on the seafloor.

Shamik Dasgupta

“Our findings mark the deepest known such ecosystem,” said Dasgupta, an associate professor at the Institute of Deep Sea Science and Engineering (IDSSE), Chinese Academy of Sciences in southeastern China, who was a member of a diving mission into the Aleutian trench.

“Such thriving communities at such great depths expand our understanding of habitats and adaptability,” Dasgupta told The Telegraph.

Marine scientists Xiaotong Peng and Mengal Du at the IDSSE and Vladimir Mordukhovich at the Russian Centre for Marine Biology in Vladivostok led the exploratory missions that covered more than 2,500km along the two trenches in the northwest Pacific. Their findings, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, suggest that such life forms are more widespread than hitherto believed.

“We’ve seen such life forms elsewhere in the oceans, but this shows they can thrive even at the ocean’s deepest extremes,” said Aninda Mazumdar, a scientist at the National Institute of Oceanography in Goa, who was not associated with the China-Russia study.

“This discovery tells us how life can proliferate even in the most hostile environments,” said Mazumdar, who had reported similar tubeworms feeding on hydrogen sulfide from sites in the Mannar basin and the Krishna-Cauvery basin in the Bay of Bengal at depths of 1,600 metres to 1,700 metres.

“The tubeworms use hydrogen sulfide vented from the seafloor and oxygen from the water to generate energy and production of biomass,” Mazumdar told this newspaper. “These are unique life forms that do not require photosynthesis — the energy source for most life forms familiar to us.”

Light begins to fade at depths of 200 metres. At depths of around 1,000 metres, there is no light — all creatures below that live in the dark.

Dasgupta, who studied at the University of Calcutta and the Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, before moving to the US for a PhD, joined the IDSSE in 2015. He has participated in 10 submersible dives and is also studying how microplastics and other pollutants might impact marine organisms, including residents of the hadal zones.