|

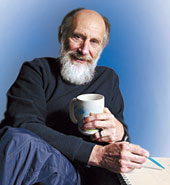

| Prof. Leonard Susskind |

Dr Leonard Susskind, the Felix Bloch professor in theoretical physics at Stanford University and one of the pioneers of string theory, is all set to add new fuel to the fire that’s now raging in the US. Although sparked off by a legal battle on a school board’s decision to teach biology in classes, at issue is humanity’s hoary question: why is the world the way it is? Is the cosmos a piece of some ‘intelligent design’ (read: God’s creation), or a sum total of events guided by the laws of physics?

Susskind’s contribution to the debate will be a book authored by him, now in the final stages of production. A draft of the book has been made available to Knowhow. The Cosmic Landscape, to be published by Little, Brown, is a physicist’s answer to those questions. Its subtitle says it all: String theory and the illusion of intelligent design. “My views in the book are about as far as one can get from intelligent design,” comments Susskind in an email interview.

But then, if you think his views will be lapped up by his own fraternity ? physicists in general and string theorists in particular ? you’re mistaken. The Cosmic Landscape may end up irking both sides of the current debate, becoming the most-talked-about popular science title in recent times.

So what’s Susskind got to say? His premise, simply put, is this: the presence of man (life, to be precise), rather than God, explains the features of the cosmos.

Strange it may sound, but scientists stumble on the so-called ‘intelligent designs’ more often than do ordinary mortals, who perceive God only in the exigencies of their lives. Researchers notice his ‘footprints’ in many phenomena ? and nowhere more distinctly than in the fact that the Universe is hospitable to life. Indeed, the conditions required for it border on miracles.

For example, all creatures are made of elements like carbon, oxygen and nitrogen, none of which is earth’s own stuff; they were cooked up in stars far away and long ago. And this cooking requires an incredibly efficient blending expertise; if the force that binds together the constituents of the nuclei of those atoms had been merely 0.5 per cent smaller or bigger, they wouldn’t be here today. Similarly, if the electron in a hydrogen atom were attracted slightly more strongly by its proton, there would be no stars, no planets ? and, therefore, none of us.

That we are woven into the Universe’s scheme of things is now enshrined in science, known as the ‘anthropic (from the Greek word anthropos, meaning man) principle’. It lifts the veil of mystery from many parameters of the cosmos. They are what they are, or else we would not be here to detect them. While this sounds like common sense, and hence is called the ‘weak anthropic principle’, some people prefer its stronger version, claiming that the cosmos was designed to host life. In the words of physicist Freeman Dyson: “The Universe knew we were coming.”

A lot of physicists, however, find the anthropic arguments repugnant, simply because they smell of religion and intelligent design. Also, to accept any parameter or law as a given seems to be a retreat from physics. Albert Einstein upheld the credo of science when he summed up the mission of his life as the quest to find out if God had any choice in setting the laws of physics. The hope, obviously, was to prove that He had none.

Alas, recent research in string theory, the branch of physics that its proponents so far believed would explain all the parameters of the Universe irrespective of our presence or absence in it, has dashed this hope. Experts have discovered that, instead of a unique Universe like the one we inhabit, the theory points to an unimaginably large number (1 followed by 500 zeroes!) of possible universes, each with different parameters and laws of physics. The ‘Landscape’ is the term that Susskind has coined to describe the entire range of such possibilities ? the megaverse. “The question, ‘Why is the Universe the way it is?’ may be replaced by, ‘Is there a pocket in this vast diversity in which conditions match our own?’” Susskind writes in The Cosmic Landscape.

If there are zillions of possible of universes, is it a mystery that some of them will be conducive to life? It’s no more surprising to find ourselves in one of them than it is to find ourselves on the moist and warm earth than on Pluto. We live where we can live, and this sets the parameters of this Universe. Period.

Susskind can guess the ripples The Cosmic Landscape will create among his peers. In its last chapter he provides an overview of the reactions that the megaverse idea has evoked since he posted it on the web archive of physicists. The list of his peers is a Who’s Who of physics, and, with typical candour, he ticks off the celebs who are for, against ? and even fence-sitters on ? the issue.

I also sought comments from some experts, including Prof. Andrew Strominger, string theory expert from Harvard University and one of those who think physics, rather than anthropic arguments, will explain the cosmos. “The current discussions of the string theory landscape are highly speculative and premature and invoke many unjustified assumptions,” he writes in reply to my email. “Personally I doubt the efforts will lead to anything new and interesting.”

Prof. Lee Smolin, of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Canada, is another physicist I contacted. A staunch critic of the anthropic principle, he and Susskind were last year locked in a debate on it in the web magazine Edge (dubbed ‘A physics shoot-out’ by it). Smolin, too, is intrigued by the lucky coincidences leading to life, but has his own idea to explain them, as outlined it in his 1997 book The Life of the Cosmos.

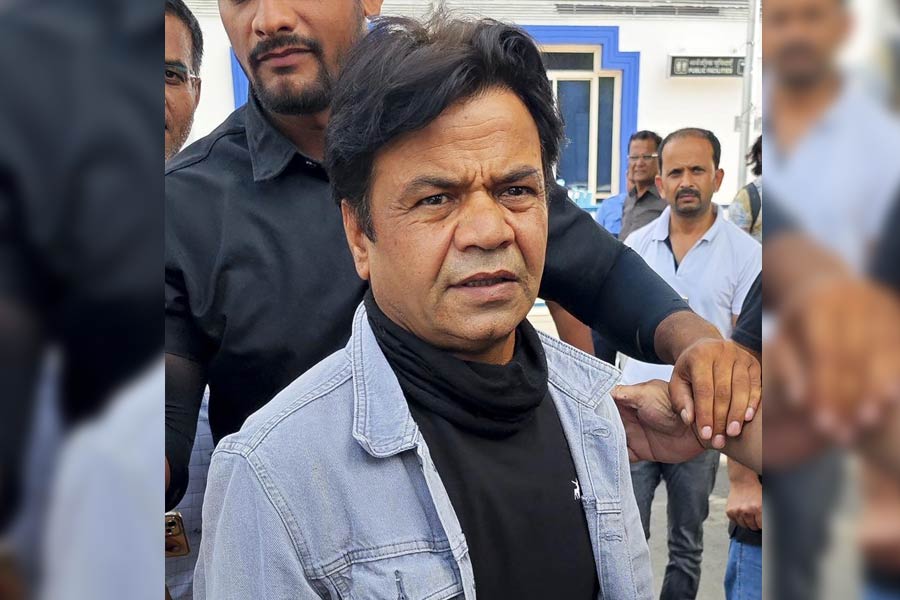

|

| Cosmic Darwinism: Prof. Lee Smolin |

His is a Darwinian view of cosmology: as massive stars die to become black holes, out their other ends pop new universes, with new parameters and new laws of physics. Only some of these universes produce stars massive enough to collapse into black holes ? and breed more new universes. Others that fail in this task die out. Cosmoses multiply like rabbits. The result: a Universe of universes, dominated by the ones that are fittest, those most efficient to breed ? that is, live long enough to make stars, planets and support life. Smolin believes our cosmos is just one of those smart ones.

Does he think accepting the anthropic principle is a retreat from physics? “This is a bit too strong, but roughly, yes,” replies Smolin in his email to me. His other objection to the principle, he says, is that it doesn’t yield any prediction that can be checked to test its validity ? a precondition for any idea to be counted as a scientific one.

I raised the issue in the email interview with Susskind. “The Landscape idea is a mathematical statement,” he writes in reply. “It says there are many possible solutions to the equations of string theory and only a small fraction have suitable properties for life to evolve. This kind of statement can only be tested mathematically. Many people are now working to determine if string theory really does have a rich Landscape. We will certainly know eventually.”

That may be his self-defence against the attack from his peers, but what about the criticism that is in store for him from the crowd that is hell-bent on believing in a supernatural intervention in the affairs of the world? Susskind emulates the example of the French polymath Pierre-Simon de Laplace to deal with it. Asked by Napoleon why his celestial mechanics had no mention of God, Laplace replied, “Your Highness, I’ve no need of that hypothesis.”