|

|

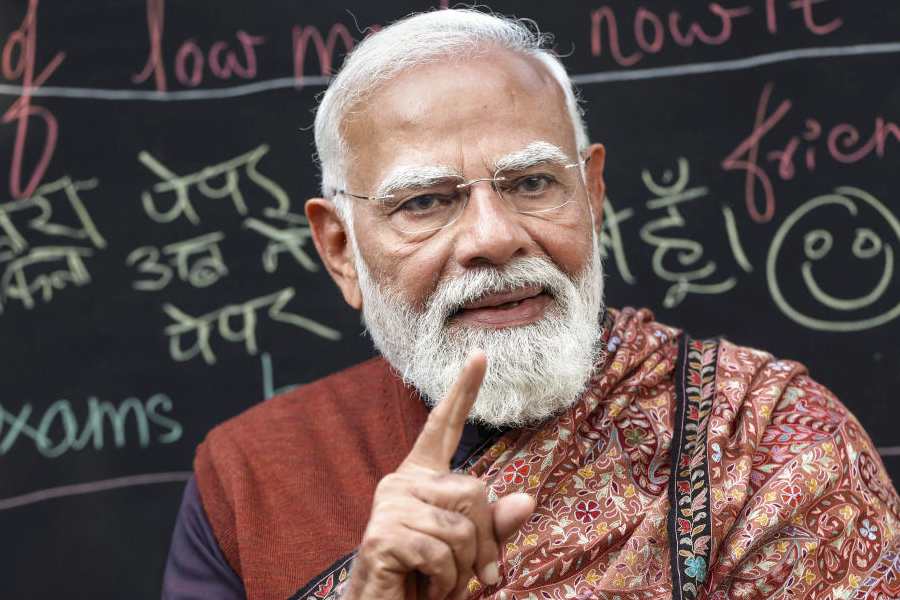

| PLAYTHINGS: Swedish archaeologist Elke Rogersdotter (above), drawings of game-related materials (below) found in Mohenjo-daro |

|

|

Sports and games are a vital part of life. This was true even in an ancient civilisation that flourished in the Indian subcontinent some 4,500 years ago.

A study, which offers a rare insight into the social life of the Indus Valley civilisation, showed that every tenth find was related to play. The Bronze Age civilisation, that stretched from Gujarat in India to Sindh in Pakistan, existed from 2,600 BC to 1,900 BC. A majority of the objects found comprised dice and gamesmen, stressing the popularity of board games in those days.

“I was astonished by the sheer quantum of play-related materials unearthed,” says Elke Rogersdotter, an archaeologist with the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, who undertook the study as part of her PhD work. “In a way, it indicates how prosperous and peaceful that society was.”

For her study, Rogersdotter chose articles from the ancient city of Mohenjo-Daro, now in southern Pakistan. She ploughed through records of the artefacts excavated from the remains that constituted the largest urban settlement of the Indus Valley civilisation. It spread across an area of 250 hectares and had an estimated population of more than 35,000. Mohenjo-Daro, like most other Indus Valley settlements, had clusters of mud-brick buildings neatly segregated into distinct neighbourhoods by broad streets. It also had appropriate sanitation and drainage systems, giving perhaps the first ever glimpses of proper town planning.

Apart from the abundance and diversity of dices and gaming pieces, what intrigued the Swedish archaeologist is the proper allocation of space for playing games. She found that gaming objects were not scattered all around, but confined to specific locations. “This abundance together with its structured distribution shows that playing was already an important part of people’s everyday lives more than 4,000 years ago,” she says.

Rogersdotter has always been keen on understanding the role of play and games in the development of human life. It was this interest that brought her to India five years ago. During this time, she studied toy materials unearthed from Bagasara, a small Indus Valley settlement in Gujarat. She also extensively studied board games engraved on rocks during the Vijayanagara rule, which existed between the 14th and 16th centuries and covered present-day Andhra Pradesh. “I recorded as many as 800 to 900 engravings that can be broadly classified into five or six types,” Rogersdotter told KnowHow from Gothenburg. Besides, there are a couple of rare board games, she says.

According to Per Cornell, Rogersdotter’s doctoral advisor at the University of Gothenburg, her work has helped bring these gaming and play objects centre stage for archaeological attention. “Previously, such objects and the topic in general were considered of relatively little importance, more an anecdote than anything else,” he says.

It’s interesting to note the frequency of items found in Mohenjo-Daro that are probably related to play and gaming, says Cornell. “I do not know what the excavation of contemporary refuse dumps would exhibit in terms of play and gaming. But it is fairly probable that the frequency relation would not be very different. This observation from the Mohenjo-Daro study can help us reflect on ourselves better and demonstrate that despite rampant differences, there are similarities between our life today and that in Bronze Age Mohenjo-Daro,” he explains.

“It is certainly an interesting finding,” says Pottentevida Ajithprasad, a professor of archaeology at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. “Rogersdotter has focused on what most archaeologists chose to ignore. Material evidence for toy carts, figurines and animals have been excavated from many Indus Valley civilisation sites earlier. It’s a matter of revisiting them from a different perspective.” Ajithprasad is himself associated with several such excavations. “It is an attempt to understand the world of recreation in an old civilisation,” he adds.

According to Rogersdotter, in traditional archaeology, traces of play and gaming have commonly been dismissed as less significant. Such remains have recurrently been seen as signs of idle pastime and thus considered less important for research.

The Swedish archaeologist believes that the objective of determining the social significance of the actual games challenges the established ways of thinking.

This approach, if nothing else, may provide an alternative, more socially embedded way of gaining insights into the ancient civilisation, she says.