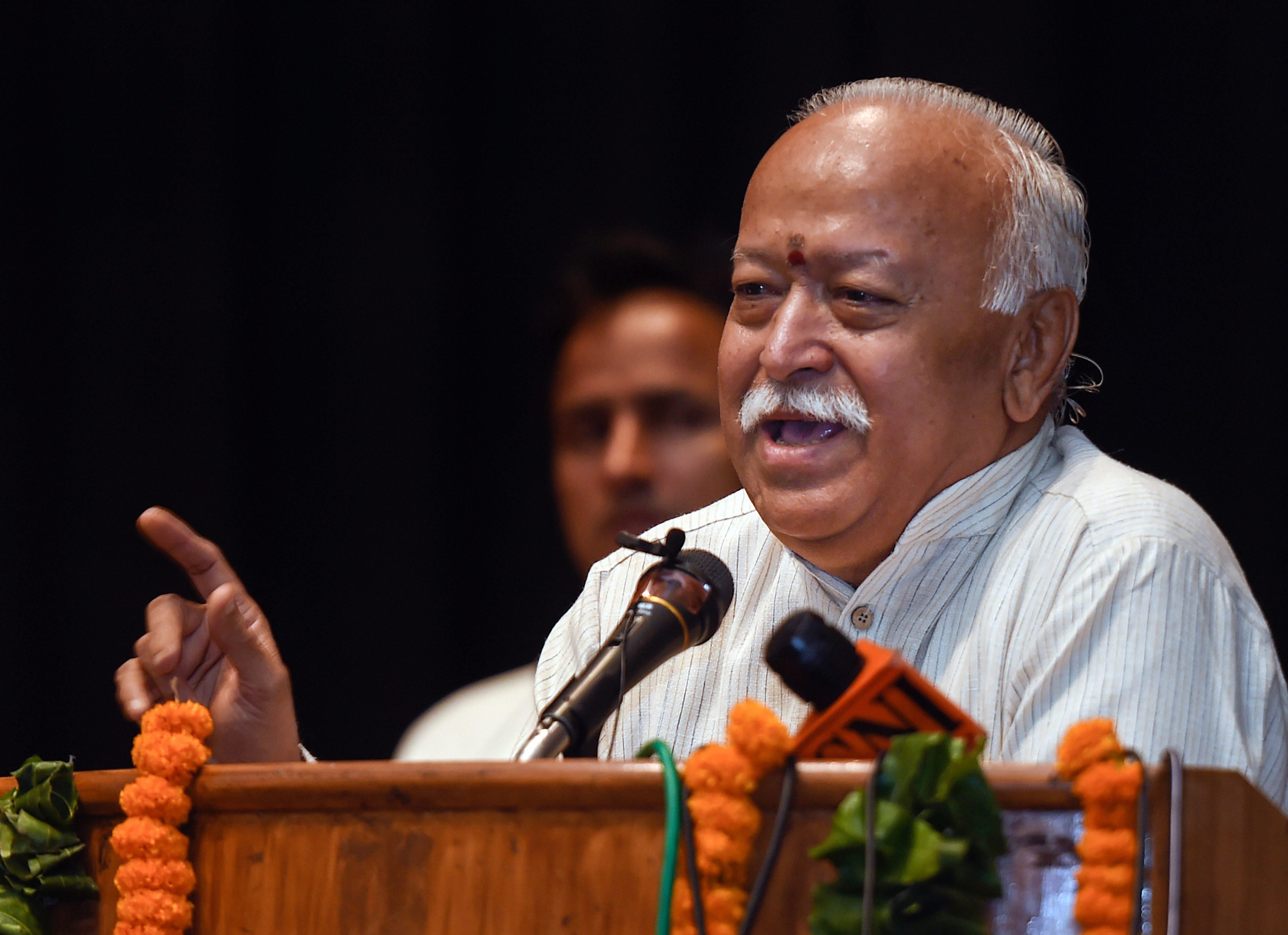

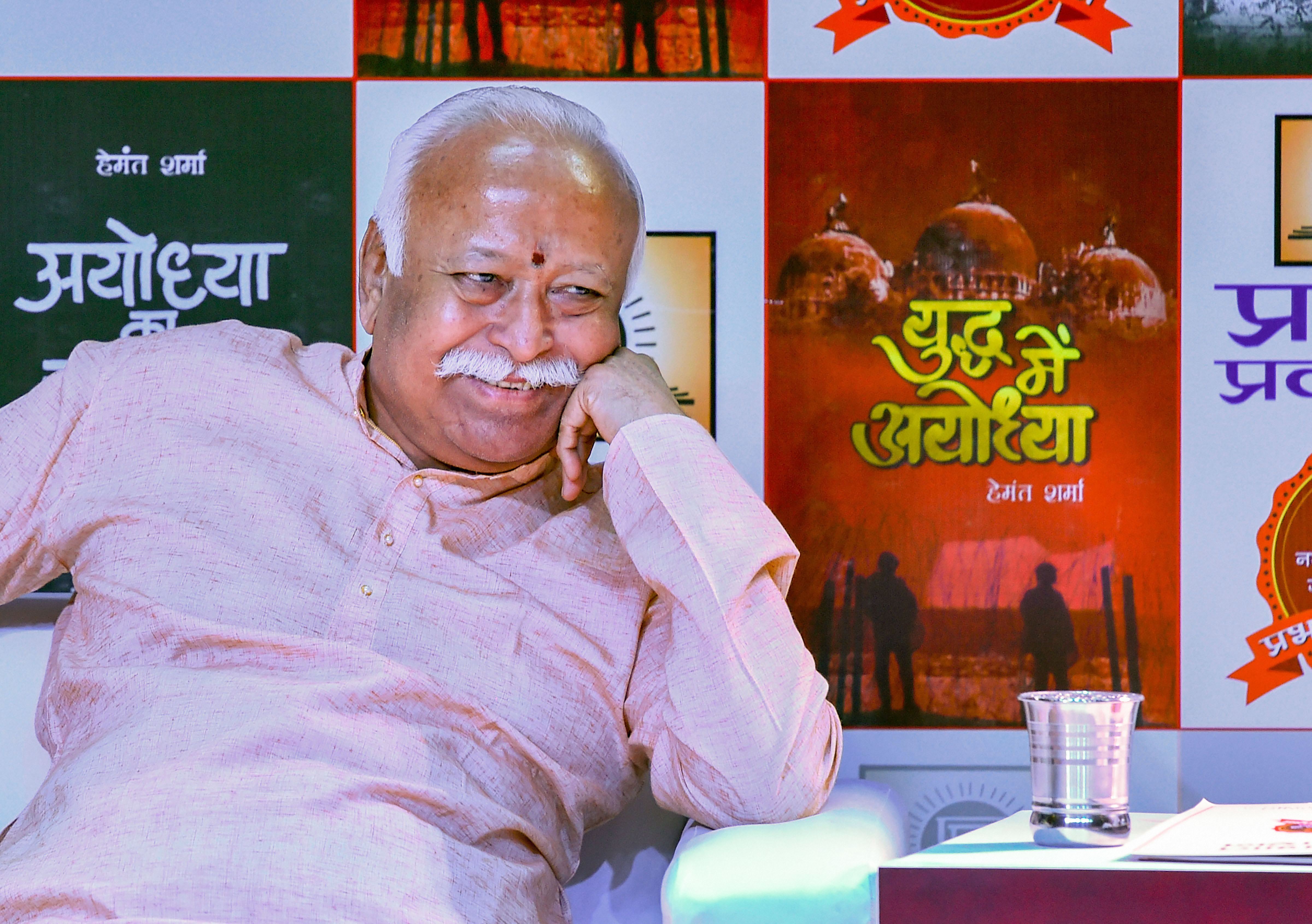

The three days of public speeches by Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s Mohan Bhagwat at a well-attended conclave in New Delhi merit scrutiny that go far beyond his headline-grabbing assertion that while India’s a Hindu Rashtra, this does not “mean there’s no place for Muslims”.

On the surface, Bhagwat’s speeches — delivered to a gathering billed as ‘Bharat of the Future’ — was aimed at promoting RSS 2.0 to middle-class India. But there’s still a whole lot more to be unpackaged and parsed from the speeches by the sarsanghchalak.

- For instance, is Bhagwat looking to put politics above social work for the RSS in this organisational revamp?

- Is he toning down the Sangh’s anti-Muslim bias? If so, is it merely a cosmetic change to give the Sangh an image makeover before the next elections and lend it more Indian middle-class appeal?

- Or is he truly attempting something much more fundamental and seeking to steer the Sangh in a new direction?

And then there was Bhagwat’s reiteration that the Sangh had discarded parts of iconic leader MS Gowalkar’s Bunch of Thoughts, including passages classing Muslims, along with Christians and Communists, as “internal enemies”.

The answers to these questions will play a key role in determining whether Bhagwat cements his place among the all-time greats in the Sangh pantheon or if this will prove be his undoing.

To understand what appears to be the RSS’s axial shift being spearheaded by Bhagwat, it’s relevant to recall that for the past 93 years since its establishment, the activities of the RSS remained confined to society or Hindu samaj and aloof from politics.

This stemmed from the belief that the correction of ills within society and unification across castes were paramount. There was unanimity from the RSS’s inception that success in harnessing and cleansing society would influence politics.

But importantly also in the history of the RSS, there are numerous instances — most famously of V. D. Savarkar who remained disdainful of the organisation despite inspiring its formation — of important functionaries quitting because of its refusal to be more political.

What marked out Bhagwat’s speeches as special this time around is that he did speak the language of politics. He put the case to the RSS faithful that this was a necessity, at least in the short-term, and he expressed the strong hope that this would catalyse changes in social behaviour.

Young swayamsevaks at an RSS camp. The Telegraph file picture

While Bhagwat’s predecessors believed society was the horse and politics the cart, the sarsanghchalak reversed that order. Bhagwat broke new ground by unequivocally attempting to guide people’s electoral choice. This was a crucial departure from before when it used to be emphasised that political messaging was not the Sangh’s task.

Bhagwat’s attempt to guide the voting process was evident in his argument that pressing the NOTA button would benefit the worst politicians. Unabashedly, he suggested people should opt for the best politicians. And he left scant ambiguity about who he considered to be the best. With this declaration, the separation between politics and the RSS would seem to have been eliminated and any pretence of retaining the claim of being merely a socio-cultural organisation would be viewed as hypocritical

Behind the advice not to waste one’s vote lies the Sangh Parivar leadership’s underlying concern about a significant satisfaction deficit among supporters with this government and the worry that they may opt for NOTA because the opposition doesn’t enthuse them sufficiently. Why is this crucial? It’s because in tight contests, choosing NOTA can make all the difference between winning and losing.

This also explains why Bhagwat decided to make his intervention now in a hastily arranged programme. The RSS, it must be mentioned, follows a rigid calendar and tours of senior leaders, called pravas in Sangh lingo, are planned months in advance. Obviously, Bhagwat’s lecture series was arranged because of a realisation that this regime needs bolstering. Also, Bhagwat’s invitation to people to come and see for themselves what the RSS does before passing judgement was clear evidence that the RSS realises large swathes of educated Indians remain distrustful of the organisation and its intentions toward the nation. Bhagwat’s clarification of the RSS’s stands on minorities, the Constitution, the national flag and, most importantly, the freedom struggle can be understood in this context.

There’s also a sense that public cynicism, which may negatively impact the electoral prospects of the Bharatiya Janata Party, is more widespread among upper castes and OBCs who are increasingly voicing opposition to the appeasement of Dalits.

By suggesting who they should not vote for, Bhagwat has indisputably overturned the socio-political thrust of previous sarsanghchalaks, most notably Golwalkar and Deoras who between them steered the RSS from 1940 to 1994. Importantly, with his speech, Bhagwat has given a politico-social turn to RSS activities. In a departure from the views of the past, he sees politics as the ultimate game-changer and believes power over state institutions will lead to desired societal change.

In short, Bhagwat was cementing the complete U-turn from the Sangh’s past abhorrence of politics. In 2014, for the first time, swayamsevaks stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Bharatiya Janata Party workers, while campaigning, manning polling booths and mobilising people to come out and vote. These speeches legitimised this partnership and left no doubt about the complete synergy between RSS and BJP in the coming elections.

Significantly, too, Bhagwat has altered the hierarchy within the RSS. Previously, each affiliate was on an even keel and RSS efforts were restricted to making each one of them self-reliant and autonomous. Under Bhagwat, independence of some has been curbed in the service of a larger goal and the BJP is now the undoubted first-among-equals.

This development will have a bearing on the prospects of affiliates which are engaged in mass programmes and depend on agitations to widen their socio-political base. Those organisations like the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, Swadeshi Jagran Manch and even the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad will find the going tough. That’s because the RSS will come down heavily whenever populist issues are raised in order to remain ahead of rivals in specific sectors.

It remains to be seen if the rank-and-file will accept these fundamental changes when they sense the raison d'être for being swayamsevaks has been turned on its head. Acquiring state power is now the primary objective as against the previous goals of social rejuvenation and change.

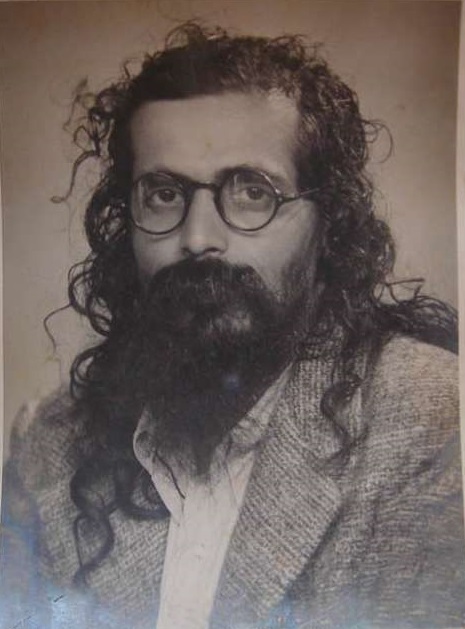

Bhagwat also has done much more than merely debunk the random assertions of MS Golwalkar, the second and longest-serving sarsanghchalak who’s reverentially called Guruji by the rank-and-file. He has declared it’s time to move on from what was said by Golwalkar in a specific historical context, asserting that Hindutva “is about unity” and that “no-one is an outsider in India”.

MS Golwalkar is the second and longest-serving sarsanghchalak. Wikimedia

Still, it’s easy to make a sweeping statement that if there were no Muslims, then “woh Hindutva nahi rahega” (it will be the end of Hindutva) but another matter to change the fundamental framework of the RSS’s responses to developments.

Bhagwat has given no indication what he proposes to do in regard to significant resolutions passed by different representative bodies of the RSS at various times. For instance, there’s the declaration of Akhil Bhartiya Karyakari Mandal in Ranchi on October 31, 2015, after the religious census based on 2011 data was published. How much of Akhil Bhartiya Karyakari Mandal’s past can be purged is the moot point.

That resolution expressed concern over the growing demographic imbalance in India by making a distinction between “religions of Bharatiya origin” and others like Islam and Christianity. The resolution stated that: “The share of population of religions of Bharatiya origin, which was 88 per cent, has come down to 83.8 per cent while the Muslim population, which was 9.8 per cent, has increased to 14.23 per cent during the period 1951-2011.”

Additionally, the RSS claimed growth of the “Muslim population has been higher than the national average in the border districts of states like Assam, West Bengal and Bihar, clearly indicating the unabated infiltration from Bangladesh”.

Bhagwat did not explain why the Sangh Parivar still expends energy and carries out disinformation campaigns claiming that Hindus face becoming a minority in their own nation if indeed Muslims too are part of Hindu samaj.

Likewise, the campaign against illegal immigrants is at odds with what Bhagwat posits. Moreover, because of this assertion, the RSS must actively pursue its Akhand Bharat project as Muslims too — from the eastern fringes of undivided Bengal to the Hindu Kush mountains — are part of a single nation.

Bhagwat also addressed issues besides the organisation’s outlook towards minorities but on most matters he deviated little from the Sangh’s ideological core. For instance, when asked if there was a necessity for a population control scheme along the lines of China’s, he replied in the affirmative but quickly added the programme should be “uniformly imposed” and prioritised “where the problem is greater and among those who can’t take care of their children” but still produce children. He added that if parents “can’t take care of their children, they will not become good (sic) citizens”. The allusion was obvious and, unsurprisingly, sympathetic sections in the audience applauded.

Bhagwat also raised the matter of internal security and batted for stronger laws without going into causes of social unrest. He spoke the language of BJP leaders by linking urban supporters with rural social disruptors. The phrase “urban Naxals” was not used but he left no ambiguity about what he was hinting at. Still, the RSS chief sidestepped a deeper examination of social alienation when discussing caste conflict and also did not state what he would do to end caste discrimination.

On reservations, however, Bhagwat has learnt lessons and now knows that challenging this policy cost the BJP dearly in Bihar in 2015. Despite this, it’s premature to expect the RSS to appoint functionaries to important positions on the basis of their caste. While Bhagwat stated caste identity is of no consideration in deciding who rises in organisation’s hierarchy, it can be expected that — barring a handful of leaders — the RSS will remain upper-caste dominated in the near future.

And also, clearly, this isn’t the last we have heard Bhagwat’s speeches or about the responses they’ll get. Still, between now and the next parliamentary elections, there seems to be clarity about the organisation being driven henceforth by a political agenda and populist phraseology. Yet, beneath the `glasnost` Ram Madhav claimed that Bhagwat heralded and the `in-house eulogy`, there remain several incongruities in the programmes and practices of the RSS that require revision if the organisation is actually to become RSS 2.0. If this isn’t done, the phrases making headlines now risk only being added to this government’s jumlas.