Michelangelo Antonioni's first film in colour, Red Desert (1964), is also a film about colour - or looking at colour. The person doing most of the looking is a woman called Giuliana who describes herself as sick beyond cure: "Everything hurts, my hair, my eyes, my throat, my mouth..." She is played by Monica Vitti, who passes unforgettably through four of Antonioni's greatest films of the Sixties - The Adventure, The Night, The Eclipse and Red Desert - before disappearing, just as memorably, into Modesty Blaise. Her beauty - blonde, blank, and bottomlessly bored - is the medium through which Antonioni discovers and reinvents, over and over again, that all-embracing hurt at the core of his sense of the Real. "What should I use my eyes for? To look at what?" Giuliana asks the man she keeps pulling to herself and pushing away. "You wonder what to look at," he replies with baffled but cold eyes, "I wonder how to live."

This inseparability of what to look at from how to live - figured in different ways in the men and women who attract and repel, remember and forget, bind and escape each other in these difficult, subtle and exquisite films - becomes, in every sense, a crisis of coupling. So, the questions that move restlessly through the films are both existential and cinematic, ethical and aesthetic; and the answers to them are never easy, the resolutions always provisional. Again, it is Giuliana who asks, and embodies, the overwhelming question, "Who am I?" And the words, tutto and niente, everything and nothing, which we keep knocking against in the films, offer something of a non-answer. "I don't know," is what Vittoria, also played by Monica Vitti, says in answer to most questions put to her in The Eclipse. After the American première of the film, Antonioni visited Mark Rothko, and then wrote to him, "You and I have the same occupation. You paint, and I film, nothingness."

To make nothingness visible, to make it live and move, was the great challenge. The personal and historical evolution of that challenge had determined the shape of Antonioni's life as filmmaker, thinker, writer and, less publicly but persistently, painter. His films are haunted by art (and by architecture), even as they become works of art themselves, edging towards an elusive avant garde that shimmers like the horizon of the sea - ever present in the films - with its promise of neo-Homeric adventure. For Roland Barthes, in an eloquent felicitation of the filmmaker made in Bologna in 1980, Antonioni's work is "open to the Modern", where the "Modern" is not "a standard to be raised in battle against the old world and its compromised values". It is, instead, "an active difficulty in following the changes of Time, not just at the level of grand History but at that of the little History of which each of us is individually the measure".

This difficulty is also the challenge that anybody trying to capture the essence of the man in photography would have to take on and deal with. Nemai Ghosh captured the essence of Satyajit Ray obsessively, and often brilliantly, by stalking him over the decades with a devotion that is now legendary. The beauty and intelligence of that body of work by Ghosh were informed, therefore, by the progress of Ray's own sensibility as an artist. In Ghosh, it was a dogged and gradual process of education that could not have happened quickly. This dimension of growing, in time, as a photographer in the shadow of an artist is, understandably, lacking in the somewhat slight body of work presented by Ghosh at the Harrington Street Arts Centre as From Films to Paintings: Michelangelo Antonioni (until today).

It exhibits some of the fruit of two brief encounters with Antonioni and his wife, Enrica, once in Calcutta in the mid-Nineties, and then in Rome at Antonioni's birthday party and exhibition of paintings in 2006, the year before his death. The photographs mix black-and-white and colour, which, in itself, is perfectly acceptable. The colour work shows a wheelchair-bound Antonioni at his drawing board. There are also grainy and badly lit installation close-ups of some of the paintings, the poor quality of photography in them unredeemed - indeed, made more glaring - by inordinate enlargement and handsome framing. These should not have been shown at all, for they do a great disservice to the artist's lateness.

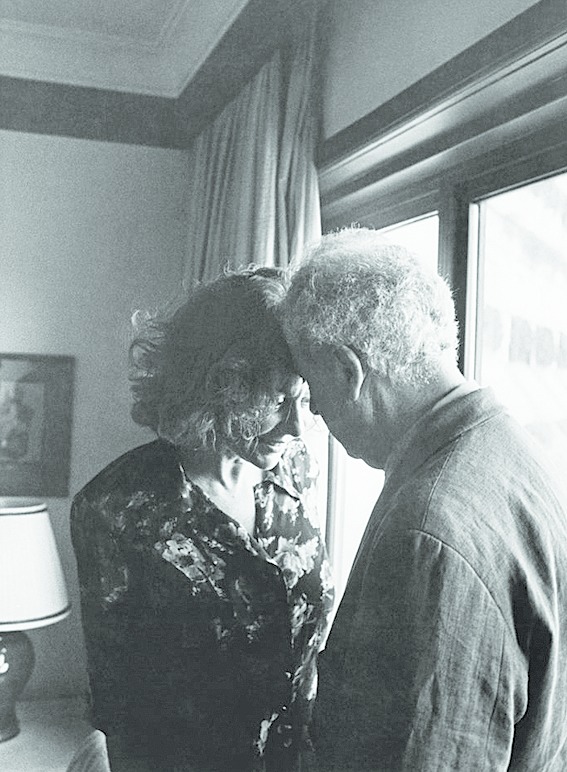

The best room is the one in which hang six large black-and-white portraits of the couple. They look as if they could have been Piero and Vittoria from The Eclipse, or Sandro and Claudia from The Adventure, come back to haunt a hotel in Calcutta, bringing with them a sense of what Pier Paolo Pasolini had called, in one of his Roman elegies, "the stupendous monotony of the mystery". In these portraits, their subjects at once elegiac and impeccably remote, we see how Michelangelo had become "the true, pure artist" for Enrica - a man she "could never quite reach", for "he was unknown, even to himself".