|

Água viva By Clarice Lispector, Penguin, £7.99 Rings of Lispector (Agua Viva) By Roni Horn, with a text by Hélène Cixous, Steidl, Hauser & Wirth, Price not mentioned

I wanted to call this review ‘Three Sisters’ — after Chekov, and a mad production I had seen years ago in London, played by the indomitable Redgraves. But I feared that the idea of sisterhood might lapse into a sort of happy-clappy feminism in the reader’s fancy, and do terrible wrong to the hard and relentless work of making, breaking and re-making identities that the three women in this piece keep pulling off in different ways, with themselves and with one another’s work. Besides, I’m not sure if they are ‘women’ at all, in that ontologically stable sense of the word. Try this. First say aloud “Clarice… Roni… Hélène…”; and then, “Lispector, Horn, Cixous”, and you will know what I mean. It’s the difference between savouring and scissoring. All three are artists of the ‘cut’. And, at its un-kindest, cutting unfixes sex into beautiful and difficult pieces of paper, rubber, film or text, which ask to be joined again, but never in a simple or straightforward way.

What we get in the relationship between Clarice Lispector’s Água Viva (1973), translated from the Portuguese by Stefan Tobler for Penguin Modern Classics, and the exquisitely austere Rings of Lispector (Agua Viva) by Roni Horn in its dust-coloured slipcase, following this writer/artist/ bookmaker’s London exhibition of 2004, is a vitally triangulated or “crisscrossed” web of writing and making. The third angle of the triangle is the essay by Hélène Cixous on Horn’s use of texts, in this work, from Lispector’s Água Viva, laid out in parallel with Beverley Bie Brahic’s English translation in Horn’s book. Horn actually draws this triangle at the end of her book, with their three names written at its three apices. She puts little arrowheads to show the different currents of appropriation, influence and exchange — of ‘conversation’ in its widest and most mystical sense — that flow along the three sides of this triangle in contrary, parallel, simultaneous, convergent and divergent directions, to make up a body of what might be called multiple “translations”, or streams of “living water” (in homage to Lispector’s original title). In Brazil — where Lispector settled (if that is the word) as a mysteriously beautiful Jewish Ukrainian émigrée until her death in 1977 — água viva would also, and more immediately, evoke a jellyfish, or medusa, with its mesmerizing tentacles and menacing mythic resonance. “I write as if to save somebody’s life,” Lispector wrote, “Probably my own.”

Cixous, whose writing eludes the academic distinctions between theory, criticism, fiction and philosophy, had learnt to read Portuguese in the mid-Seventies to do justice to the profound influence on her of Lispector’s tales, essays and fragments, which — as she writes in her note on Lispector in Horn’s book — “each, and every time, revolutionize literature”. Cixous calls her own efforts with Lispector’s language — which remained the most foreign thing about Lispector, like Conrad’s English — “submission to the process”, and it is Cixous’ rigorous, yet blissfully freeing, immersion in Lispector’s body of writing that drew Horn to both Lispector and Cixous for the first time. Cixous went on to become for Horn a subject, muse and addressee in her own right, inspiring Horn to make a book called Index Cixous with her photographic portraits of Cixous, which could be mistaken for a Gallimard novel.

Cixous was one of four artists and writers — Louise Bourgeois, Anne Carson and John Waters being the others — to whom Horn sent the same list of titles of her own works. Each was then invited to “annotate” Horn’s titles in his or her own way, so that each person’s annotations became a literary/artistic work in its own right, but together making a four-volume book-work called Wonderwater: Alice Offshore, whose ‘author’ remained Roni Horn. It is important to understand this dissolution of unitary authorship in many of Horn’s books and installations, for it gives to the radical liquefaction of identity at the core of her work a series of precise yet paradoxical material forms. They are paradoxical because conceptual, and hence authorial, control over the work is never relinquished in the process of realizing its plural authorship. This, in turn, helps us to understand how Rings of Lispector, the installation, and Rings of Lispector, the book, stand in relation to each other. The book is not just a catalogue of the installation, but an autonomous work, and Cixous’ essay in it is not a catalogue essay but an integral part of this book, tying in with the ongoing Cixous-theme in Horn’s larger corpus of books. Together, installation and book bring about what Cixous describes as “the transfiguration of the lispector world into the horn world” by something like a “mirror trick”.

The coupling of book and book, or book and work, is inseparable from how Horn, Cixous and Lispector understand and represent the relationship, not only between the Self and various forms of the Other, but also between text and reader, artefact and viewer. For Lispector, this opens up the relationship between I and Thou to a third entity, the It, which is everything in the world that resists internalization, taking writing “beyond thought” towards the impersonal, and even the inhuman. This play between You and Me, which pervades Horn’s art and writing, takes on in Lispector’s text the intrigue of a hidden love story, whose narrative trappings are carefully edited out of the final version, leaving a dangerous vacancy into which the reader gets pulled in: “You are a form of my being me, and I a form of you being you: hence the limits of my possibility.”

Fragmentedness is built into the genesis of Lispector’s book of apparently random, degree-zero reflections. She wanted it to read like “life seen by life”, yet be informed by the irreducible sensual coherence of chamber music — “chamber writing”, she called it, “a quartet of nerves”. “It was like a puzzle,” her editor, Olga Borelli writes, “I took all the fragments and collected them and kept them in an envelope. On the back of a check, a piece of paper, a napkin… some of them still even smell of her lipstick. She would wipe her lips and then stick it in her purse… Suddenly she noted something down.” Yet, as in all works of art, the randomness coexists with a continual anxiety about the improvisation of form: “My internal form has been carefully purified,” she writes, but “I plan nothing in my intuitive work of living: I work with the indirect, the informal and the unforeseen.”

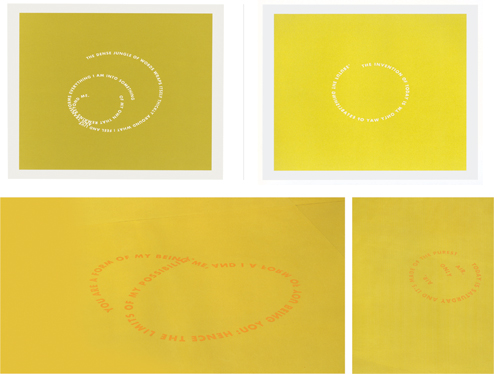

It is this self-conscious surrender to what she calls the “oblique life” that creates the “circumvolutions” of her writing, which attain only fitfully “the vital sensuality of clear structures…the curves that are organically connected to other curved shapes”. Roni Horn’s “rings” extract Lispector’s “circumvolutions” from the realm of the book and free them into the actual space of a room, but displace them to a disconcertingly different plane of experience (bottom left and right). The floor is entirely covered from wall to wall with coloured rubber tiles inlaid with rubber texts, upon and around which the viewers would have to walk. Their bodies meet through their feet the oddly resistant elasticity of a substance that lends to the “lightweight presence” of Lispector’s disembodied sentences an organic tactility. “Rubber changes your relationship with the world,” Horn tells Cixous, “It yields and does not betray.” “At this point,” Cixous adds, “a new kind of walking, of stepping, of reading, from a distance, askance, is born.” These texts are also installed vertically as 17 silkscreens on paper, and subtitled “Seventeen Paradoxes” (top left and right). Here they become broken rings of language, at once open and closed, knocking against, sometimes floating along, the confines of their frames like fragile escape artists caught in a “dual realm...half-language, half physical/metaphysical.”