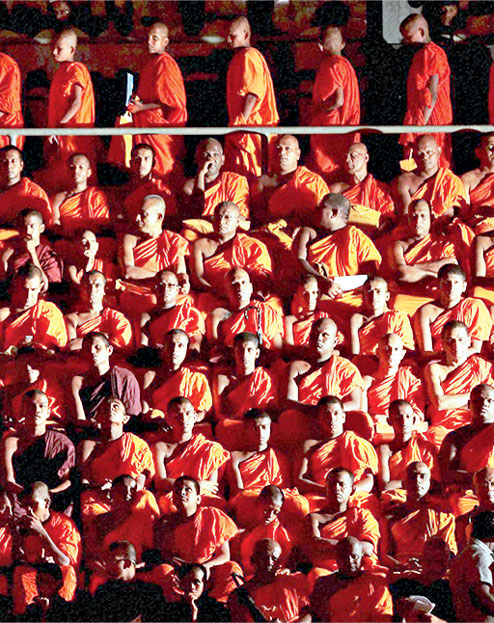

" It is a serious thing for a village to have no monk." - H. Fielding-Hall, The Soul of A People, 1898

The ICS, in British times, was a set of small-minded, small-sighted, small-feeling men. But there were great exceptions to this. H. Fielding-Hall, who served in India and Burma, mostly in Burma, was one such. His book on the people of the Irrawaddy, from which the head-quote to this column is derived, was one such. He shows an understanding of the thoughts, ideas and feelings of the Burmese people which, in spite of many generalizations and over-simplifications, remains unparalleled for its insights, its descriptions.

He knew its big cities - Rangoon and Mandalay - its small towns, its villages, hamlets. He knew its precipitous mountains and the stubbly fields on which he trudged, rode and fought during the third Anglo-Burmese war. He knew its rivers on the wide breasts of which he 'poled', its forests so dark and yet so full of myriad lights, some that filigreed in through leaves, some that streamed in like a great shaft of awakening. But more than all that, he came to understand, dimly at times but blazingly at others, the mind of the Burman villager. And of that villager's unique relationship with the village monastery, the village monk.

The monk, he explains, was no scholar, no philosopher, certainly no genius. But he was there, to teach the lads to read, write and do sums. He was there to receive alms and impart the importance of sharing, giving, and of renouncing. And when - rarely - the monk was found to be a hypocrite, the village hounded him out of its precincts. Himself he disgraced, never the dhamma.

Fielding-Hall says: "[Monks] are not honoured for their wisdom - they often have but little; nor for their learning - they often have none at all; nor for their industry - they are never industrious; but because they are men trying to live - nay, succeeding in living - a life void of sin."

For a village to have no monk was to be insecure, bereft.

India has always been a village. Be it ever so urbanized, ever so built-up, it has stayed, and stays, a village. In the way it thinks - narrowly, punily, myopically now and astoundingly, space-time shatteringly at others, it has been and remains that. A village of many parts, many loathsome ills, many subliminal beauties.

But today, it lacks that which holds the village together. It has no monk.

I am not talking of 'village India', but of 'India Village'. The village that India is today, not of the idealized Bharatvarsha but of Bharat Gaon. That India has no one to honour today, none to look up to. To 'look up to', not for life-support, for we are a self-supporting people, contriving survival out of misery, life out of death. But to 'look up to' for the gift of example, the blessing of an availability that shelters, elevates, redeems. And because we have had such 'monks', such exemplars, it is a deprivation not to have them now. It is a great loss. It is a wretchedness. It is, in fact, a bereavement.

So used are we as a people to 'making-do', to accepting the swipe of loss, the smite of grief, that we do not collapse. But we pay for it. Bearably, in the loss of immediate opportunities, heavily in the loss of destinations further afield where hope mingles with destiny. The 'tryst' - oh, that overdone word - which a cushion-seated part of India imagined for the whole of it was founded on the belief, so honest and so naïve, that there would always be exemplars in every city, town, village of India, the 'monks' of Mission India. Exemplars who by their vision, but more by their example, would lead us out of the rottennesses of our individual and collective lives.

Monks of that kind the freedom struggle gave to Bharat Gaon. Self-abnegating, self-sacrificing, perhaps self-deluding as well. But very soon, the monks began to drop in number. Some just aged and died. Others gave up the robe. But even as monasteries of self-denying service became temples of self-aggrandizement, monks became priests.

Today, India has shrines, it has no sanctum.

It has worship, it does not have prayer.

It has beliefs, it has no faith.

It has priests, it has no monk.

And it is a serious thing for the village - India Village - not to have a monk.

Thought has been overtaken in India by intelligence, wisdom by sharpness. It only follows that scholarship is suspect, history looked upon as a conspiracy of dates against dicta, facts against fantasy. And philosophy? That daughter of audacity and, equally, of responsibility, is today a waif. An orphan of the marketplace of mental sales, intellectual deals, political gambits where bids are made, the heaviest purse carrying the day.

Gandhi valued the village life, Ambedkar loathed it. Both, however, were monks, the latter becoming, formally, an upasaka, a lay monk in the Theravada sense. With Jawaharlal Nehru, a Buddhist thinker at the core of his being, they were monks not of village India or rural India but of India Village, a loosely-knit but cohesive family of disparate people united by new nationhood. In terms of the clichéd 'simple living and high thinking', the freedom struggle in India gave us a harvest of monks, more than one in each state, of which Utkalmani Gopabandhu Das and the Buddhist thinker, Acharya Narendra Deva, stood out, with Vinoba Bhave, Jayaprakash Narayan, P. Sundarayya, enriching Narendra Deva's example, each in their own way.

Gopabandhu's Sakhigopal, Tagore's Santiniketan, Gandhi's Sabarmati and Sevagram were monasteries of the highest type, not because they produced ascetics or brahmacharis or scholars - they did not - but because they held up an example of sheer honesty of purpose and means. And they wanted change, not some dramatic change from poverty to riches, but from injustice to justice, exploitation to fair-play, from 'sinfulness' to a life lived by ethical codes. Our Constitution was a document of atonement as much as it was a blueprint for development. Nehru's cabinet, like Mandela's decades later, tried with honest diligence to build an Asokan nation.

Asoka was not a monk. But he led a life of monkhood. The monkhood that relinquishes power for influence, strength for spirit, status for stature. And he became, and made his nation become, all the greater for it.

A monk may or may not be a saint. A monk may or may not be male. A monk has to possess one capacity. And that is the capacity to feel and make others feel remorse. Asoka felt remorse. The word for remorse that he uses in his Rock Edict XIII is derived from the Sanskrit, Anusochana. The Magadhi-Prakrit that he uses - Anusaya - is, for all its soft-pebbleness, even more powerful than the great rock of its Sanskrit forebear.

India has abandoned monks, it has abandoned remorse, the State leading the abandonment.

And then there is an irony as well.

The monk has gone, the priest has come. But our priest is no Kautilya either. He has the cunning, but not the learning. He has the guile, but not the style. He has the 'body' of the village, not its soul.

One can understand, in pure logic, a dumping of Asoka for Krishnadevaraya, a Dara Shukoh for the Alamgir, a mass replacement of monks by pandits.

But that is not what we have got.

We have a tableau of pure tinsel, where the goal has shifted from the realizable personal to the un-realizable 'national'. You may be miserable today, you will be great tomorrow. You may have nothing in your hands now, your progeny will have plenty a decade, two decades, five, ten, twenty decades from now, in a world that chants India, India, India.

To return to Fielding-Hall again. Deeply attached to the monk-led Burman that he was, Fielding-Hall nursed his doubts.

"I do not think his will ever make what we call a great nation. He will never care to be a conqueror of other peoples, either with the sword, with trade or with religion. He will never care to have a great voice in the management of the world. He will never be very rich, very powerful, very advanced in science, perhaps not even in art, though I am not sure about that. But in his own idea his will be always the greatest nation in the world, because it is the happiest."

Being a great nation may be a great ideal.

Being an unhappy people is a great sadness.