In his pastoral poem, Arcadia, published in Naples in 1504, Jacopo Sannazaro envisions a surreal landscape in which a group of shepherds sing while keeping a watch on their flocks. Among these shepherds is a priest, and he declares - in language that will send delicious chills up the spines of any aficionado of modern horror - that he often morphs into a wolf after nightfall. He does this not to attack the sheep, but to travel with other wolves and figure out their objectives. In other words, he is a spy in the animal world.

Was the poet jesting when he indicated that he might believe in werewolves? Evidently not, for the myth of the werewolf finds its roots in western European folklore, and even appears in the high culture of the Renaissance. The German Renaissance artist, Lucas Cranach the Elder, made a woodcut dating from 1512, in which parental warnings of "that thing in the forest" come to life graphically: it depicts a woman at the entrance of her cottage, screaming while a man, with claw-like hands and a beastly, bearded face, crawls on all fours and carries off her child in his mouth. People were also repeatedly accused of being werewolves in France right up until the 18th century.

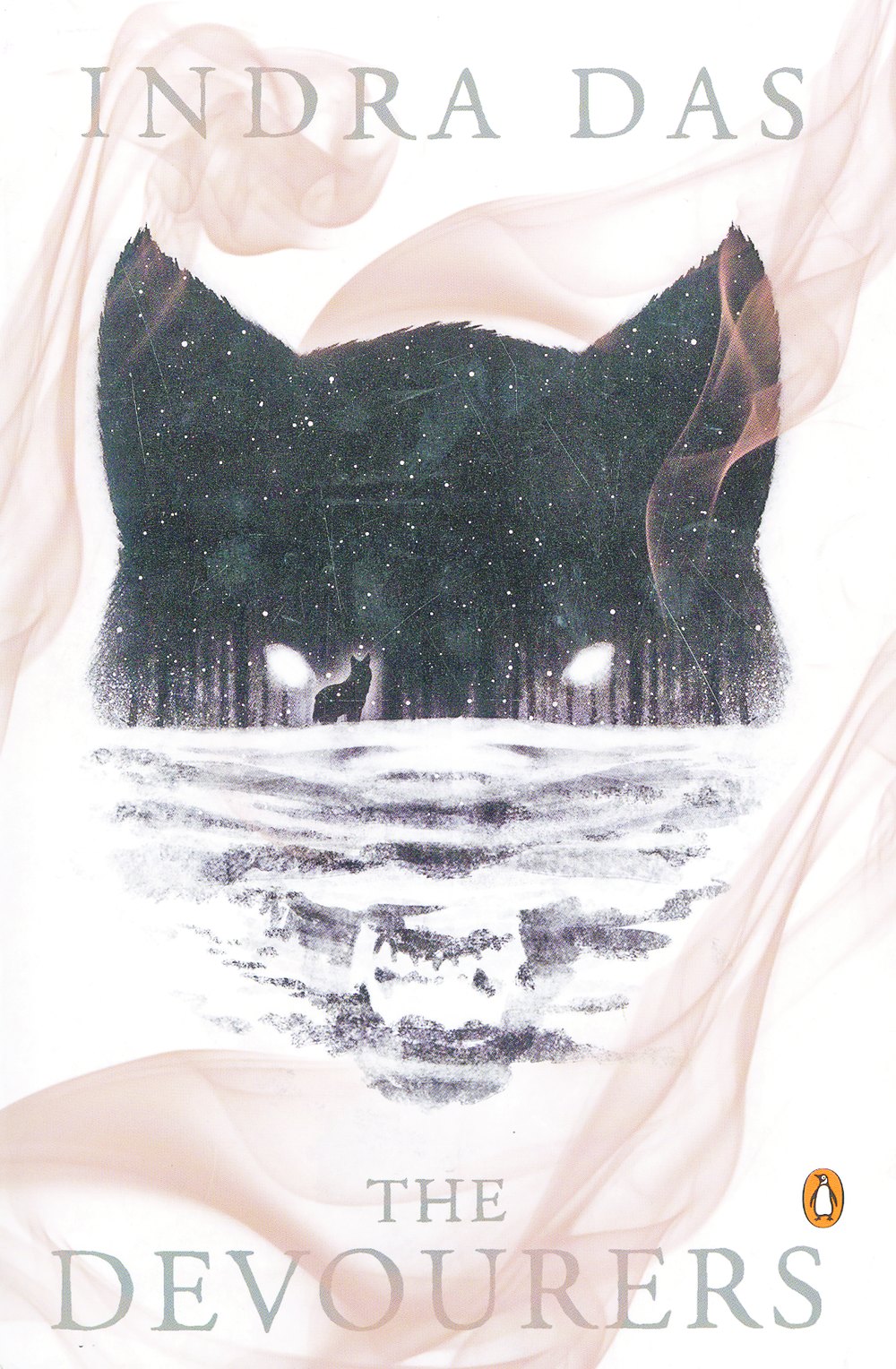

Cranach culled the werewolf from Sannazaro's Arcadia and set it free to roam where it belongs - the forests of Germany. Now, Indra Das, by a stroke of brilliance, has taken them out of the woods of Renaissance Europe and brought them to India. His debut novel cuts across centuries, from the time of the Mughals to Calcutta in the 21st century. The writing of speculative fiction by Indians has been woefully sporadic; thankfully, The Devourers breathes new life into the literary genre and takes it to an altogether different plane. If you're faint-hearted, The Devourers is certainly not for you - the author's language is feral and cruelly precise; it tears at the flesh of the fantasy genre, strips it of its skin and and uncovers the fierce, shadowy pulsing that lies concealed. Das takes his readers on a thrilling journey through the ages.

The novel keeps moving back and forth between narrator, space and age, telling a stirring tale of redemption involving three shape-shifters, Fenrir, Makedon and Gévaudan (owing to internal battles and conflicts with other tribes, their numbers have steadily dwindled from the original pack of about 45 that fled from France and Bavaria to escape oppression), their children, and a human companion - a Muslim woman named Cyrrah. In the first of the book's seven segments, a young professor, Alok Mukherjee, at a baul festival in present-day Calcutta, is "disarmed by [the] androgynous beauty" of a mesmerizing man who reveals that he is half-werewolf and lights the professor's cigarette for him. "Intimacy lies in the body and the soul, in scent, in touch and taste and sound. A man whose name you don't know can tell you a tale to move you to tears," says he to Mukherjee, sensing the recently-separated professor's utter desolation. It is with these hypnotic words that the man - he is later revealed to be Izrail, half-human and half-werewolf, son of Cyrrah, whom Fenrir fell in love with - starts to tell Mukherjee his tale. And in the telling of the story, Izrail's deft, ancient, mythical lexicon predominates - "khrissal", for example, is what the werewolves call people when their feelings and physical selves have been consumed by the shape-shifters. Later, in the smoky, liquor-addled haze of Olypub, Izrail gives the entranced Mukherjee parchments made of skin and asks him to translate the text in them. It is only after much time has passed that Mukherjee will discover the terrible origins of these scrolls - they chronicle events of violence and bloodshed (some even involve bets on the head of a Mughal emperor) that the anxious shape-shifters encountered regularly after their flight from France.

Das's superb narrative evokes the past. This is, in part, personal account, and in part a chronicle of India's history of shape-shifting. The author's unwavering dedication to the authenticity of the world that he creates is laudable - this commitment is evident in the manner in which he re-imagines the legend of the werewolf, as well as in his ruthless, grisly descriptions of the shape-shifters tearing flesh. His prose relentlessly pulsates with life; it is stark and achingly lovely. And the devourers, much like the bonds they forge, keep changing, especially while coming into their 'second skin'.