Long before a raging gale in the form of Narendra Modi swept aside Lal Krishna Advani from the leadership of the Bharatiya Janata Party in 2013, the grand patriarch had already fallen from grace in the eyes of his ideological brethren in the sangh parivar.

The fall took place on June 4, 2005, when Advani visited the mausoleum of the founder of Pakistan and penned a fulsome tribute to the man generations of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh members had been taught to loathe.

In the register at the mausoleum, Advani wrote: "There are many people who leave an inerasable stamp on history, but there are very few who actually create history. Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was one such rare individual."

Advani went on to recall Jinnah's address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947 and described it as "really a classic, a forceful espousal of a secular state in which, while every citizen would be free to practise his own religion, the state shall make no distinction between one citizen and another on grounds of faith. My respectful homage to this great man."

His words created a storm back home and he was privately reviled and publicly isolated within his party. Although he was allowed to remain BJP president for a few months, the RSS made it clear that he would have to step down by the end of the year. Advani led a dispirited BJP to a second consecutive defeat in 2009 but after the Jinnah episode, he never recovered the status that he had long held as the premier ideologue of the party.

Advani has never quite explained what made him suddenly turn dewy-eyed about Jinnah and we can only speculate on the deeper political and psychological reasons that lay behind it. It is possible that Advani - the man singularly responsible for leading the movement to demolish the Babri Masjid that was the biggest assault on free India's secular fabric - sought an image makeover in the hope of becoming more acceptable to a broader constituency.

And he found a kindred spirit in Jinnah who succeeded in dividing India on religious lines and then - after the bloodiest orgy of violence and the biggest mass migration of people ever witnessed in history - chose to blithely extol the virtues of secularism in that much quoted August 11 address.

Even if the two men were sincere in their belated recognition of the follies of fomenting a religious identity-based politics, neither could undo the lasting consequences of their past championing of it.

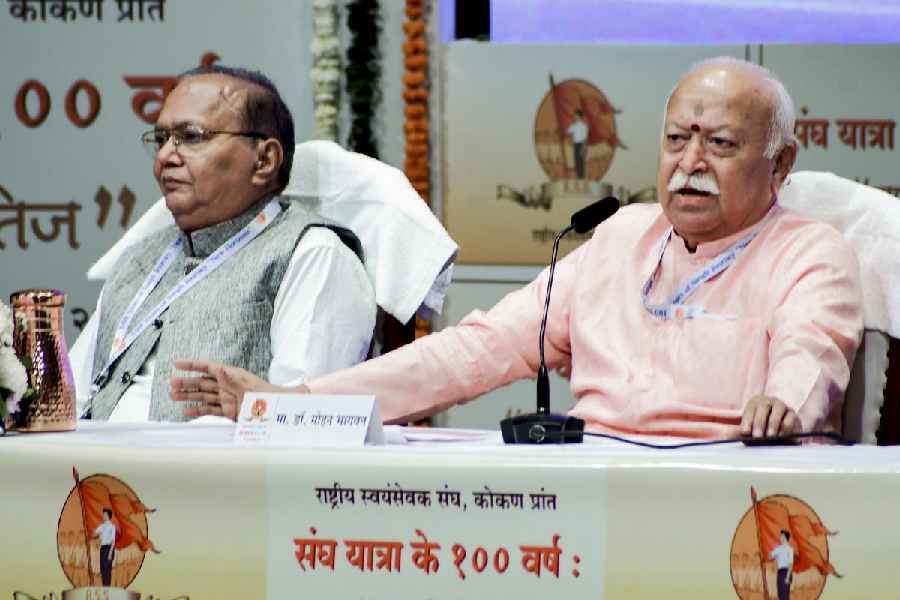

Advani's praise for Jinnah may have become a forgotten footnote in history. But as India celebrates the 70th anniversary of Independence and Pakistan too turns 70, a bigger irony is unfolding: the sangh parivar now ruling the country is paying a much more profound tribute to the founder of Pakistan than Advani ever did.

Reams have been written about Partition in the last seven decades and each year brings yet more works of research and scholarship on the subject. The "divide and rule" policy of the British raj, the naiveté of the Congress leadership which did not take the demand seriously till it was too late, the dizzying pace of events in the aftermath of the Second World War when the British were in a hurry to leave and the nationalists showed equal haste in wanting freedom, the rapid spread of communal violence in that period have all been analysed in excruciating detail - and generations of Indians have believed that Partition was a colossal tragedy that could have been averted if the leadership on both sides had been more far-sighted, accommodative and patient.

This belief was bolstered by the fact that the Congress - which before Independence insisted that it represented all communities and not just the Hindus - continued to maintain and implement that stand even after the horrors of Partition. Jawaharlal Nehru, the most ardent champion of secularism and India's composite heritage, may have failed to avert India's division but he resolutely laid the foundations of a secular republic that - for all its flaws and imperfections - not only gave a sense of belonging to India's many minorities but also allowed space for the myriad diversities within the 'majority' to flourish.

Pakistanis, for the most part, have viewed Partition very differently. With more Muslims remaining behind in India, Partition did not deliver the "Muslim Homeland" as envisaged by the leaders of the Muslim League, but there has always been a large measure of support for Jinnah's two-nation theory.

The Muslim League may have been formed as far back as 1906 but the idea of Pakistan took birth at the Lahore session of the League in 1940 when Jinnah forcefully argued that Muslims and Hindus were two separate nations and in spite of living in close contact for a thousand years could not "be expected to transform themselves into one nation merely by means of subjecting them to a democratic constitution and holding them forcibly together by unnatural and artificial methods of British parliamentary statutes".

The break-up of Pakistan with the formation of Bangladesh in 1971 and the internal turmoil within the country between sub-nationalities underscored the infirmities of the two-nation theory and was ample proof that religious identity cannot be the glue that keeps a nation together.

But the biggest refutation of the two-nation theory was India's vibrant secular democracy that was no mere constitutional abstraction but part of everyday lived reality manifest in food and music, films and clothing, sports and culture, imbuing all Indians with a sense of a shared history and a common destiny.

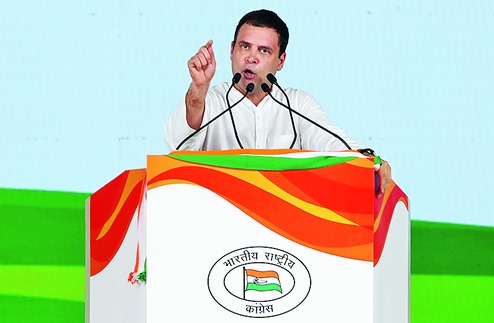

That history and that destiny are now under threat. A combination of neglect, complacency and opportunism had frayed the secular fundamentals of India for some time past. But in the last three years, it is being ripped apart - sometimes violently, more often insidiously. The prime minister may go on making lofty speeches about creating a "New India", go on repeating the shibboleth of " sabka saath, sabka vikas", but the sangh parivar's foot soldiers and storm troopers make no bones about their mission to make India a Hindu rashtra.

It is not just the lynchings in the name of cow protection that mark this mission. It is in the daily invocations to a nationalism imbued with Hindutva: making the singing of Vande Mataram compulsory in schools, deleting Mughal history from textbooks, altering facts to glorify a mythic Hindu past, uttering cries of "Jai Shri Ram" at official functions, imposing diet codes on everyone during Navratras, abusing an outgoing vice-president for expressing the same concerns that an outgoing president did because the former is a Muslim and the latter is not.

Pakistan underwent a similar stifling in the name of Islamization after Zia-ul-Haq seized power. But in India, we cannot blame unelected clerics or army dictators or a conquering power for imposing a new order upon us. It is a democratically elected government which rules India after all, and rules in our name whether we like it or not.

Jinnah, in that same 1940 speech, had evoked fears that a democratic system where Hindus are in a majority would only lead to a Hindu raj. Those ominous words ring truer today than ever before in the last 70 years.

But today is also a good day to remember that the accommodative ethos of India triumphed over the frenzy of hate that gripped the country during Partition seven decades ago. That the reservoirs of hope and resilience still run deep in this land even when silent and invisible. That the deep bonds that bind the Indian people may take some hard knocks but can never be permanently breached. That is why, try as they might, the RSS and its affiliates will, hopefully, never succeed in proving Jinnah's dark prophecy about India right.